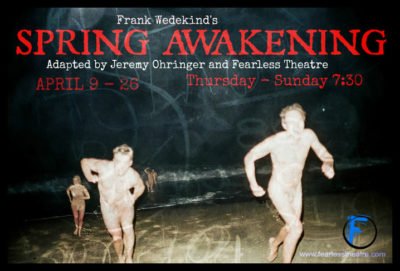

Spring Awakening

By Frank Wedekind

Adapted and Directed by Jeremy Ohringer

Produced by Fearless Theatre, Chicago

At Charnel House, Chicago

Young Company Flexes Creative Powers

Spring Awakening has been a favorite of teenagers since a rock musical adaptation by Duncan Sheik and Steven Sater in 2006 breathed new life into Frank Wedekind’s indictment of how youth are neglected and mistreated. Now, an original adaptation is being performed by Fearless Theatre, a new company made up mostly of students currently studying theatre or recent graduates. Since their goal is to do works about the lives of teenagers, Spring Awakening was an inevitable choice. Although it’s still basically the same story which I think a lot of people have a love-hate relationship with due to its heavy-handed, but justified complaints, director Jeremy Ohringer and his creative ensemble found some innovative ways of keeping the show current, which demonstrate a promising future for these artists and reward the audience’s time.

In Germany in the 1890s, a class of fourteen-year-olds are confused, excited, and anxious to be going through puberty. Free-thinking Melchior Gabor (Sammy Zeisel) mentors his older, but less mature, buddy Moritz (Nick Hyland) in how to handle erotic dreams, since no adults will discuss the subject. It’s far from the only thing the adults won’t discuss, either. While Melchior is a good student despite his contempt for his elders’ repressive morals, Moritz has extreme difficulty learning through the school’s methods, and is facing expulsion. He’s not popular among the other boys, and is convinced his parents will disown him if he fails. Meanwhile, Wendla Bergmann (Charlotte Cannon) is discussing with her friends whether Melchior or Moritz is cuter, Wendla favoring Melchior, when one of the girls reveals she is beaten by her father. Wendla is frightened and feels helpless, and reaches out to Melchior for understanding. But Melchior isn’t really that wise in practice, and their latent sexual feelings emerge in a sadomasochistic manner neither is prepared to negotiate.

Though the names and the way the school is structured root this play in the nineteenth century, Ohringer wanted to explore how the struggle for sexual knowledge seems to be refought every academic year. To that end, the actors wear clothes (designed by Cannon) that could be their own, and the dialogue has been completely overhauled to sound more plausible. The performance begins with a party, and the play cycles back to this event several times, establishing a time loop as a metaphor for ignorance and persistent culture wars. Another bold dramaturgical choice was the omission of all adult characters. It makes the teens each other’s main onstage antagonists, but the adaptation makes clear that they are not the true source of each other’s problems, and avoids the straw man depiction of adults that always risks turning this show into an immature screed.

This is the first time I’ve reviewed a cast almost all my age, and I was glad for how much they fleshed out their characters. This Melchior is a very flawed protagonist, even more so than in the original or musical versions. Another one of the adaptation’s innovations was to give Moritz a crush on Melchior, which Melchior seems to encourage without reciprocating. My impression was that he was not so much a predator as so used to being the only one with an informed opinion he never learned to respect other peoples’ feelings, though I still can’t fully explain his raping Wendla. Zeisel understood this aspect of the character enough to give the story a nuance it lacks when done poorly, though the rest of the cast provide him with ample help. Wedekind’s script granted Moritz more knowledge and dignity than the musical, and Hyland uses this to craft a character who is far more relatable and a victim of circumstance as much as neurotic. Cannon’s Wendla has a flirtatious grace and a warm heart, and Danielle Pereira’s Helen, a nearly mute girl who intently listens to everyone, is a particularly captivating part of the twelve-person ensemble.

Ella Pennington also has an intriguing role as Ilse, the girl who ran away to an artists’ colony. Spacey and self-destructive though she is, Ilse sees the beauty in all her peers, and delivers this adaptation’s call for youth to unite together to create a future not ruled by cruelty and stupidity. Fearless Theatre teams up with a charity for each project, and their current partner is Youth Empowerment Performance Project, a group which does therapeutic theatre for homeless LGBT teens. I still take some issues with Spring Awakening’s plot. Why would anybody presume suicide if a body was found with a gunshot wound but no gun? Why are people who raise livestock so ignorant about breeding? But for the purposes of community engagement, developing the skills of young artists, and putting on an interesting show, this adaptation is a worthy addition to the Chicago theatre scene. I especially encourage fans of other versions of Spring Awakening to attend.

Recommended

Jacob Davis

[email protected]

For more information, see Spring Awakening’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing at the Charnel House, 3421 W Fullerton Ave, Chicago. Tickets are $15, free for high school students with ID. Performances are Thursdays-Sundays at &:30 pm through April 26, except April 23. Running time is eighty minutes with no intermission.