A Small Oak Tree Runs Red

By Lekethia Dalcoe

Directed by Harry Lennix

Produced by Congo Square Theatre

Playing at the Athenaeum Theatre, Chicago

There are some images that will never leave your mind, if Lekethia Dalcoe has anything to say about it. The latest product of Congo Square’s August Wilson New Play initiative, Dalcoe’s A Small Oak Tree Runs Red puts a horrifying twist on the concept of a memory play, with the ghosts of three historical lynching victims struggling to remember and come to terms with their experiences. Director Harry Lennix calls the play an allegory, in reference to African-Americans’ desire to learn more about their history, but also a fantasy in which justice and redemption come from a clearer path than they do in real life. While it’s true that the play takes place in Purgatory and is therefore arguably optimistic, the journey is intensely disturbing.

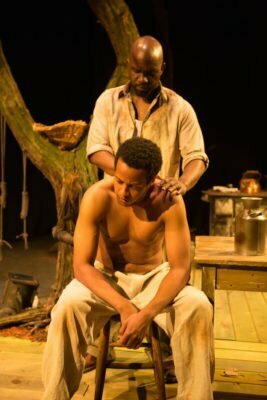

The first image we see onstage is scenic and props designer Andrei Onegin’s gnarled, scraggly tree bursting through the floorboards of a long-abandoned cottage. The thing practically drips evil. Ropes, some with nooses intact, other cut, dangle from it, along with rotted bolts of cloth and sheets of paper. The three actors enter wearing nooses, and the men start off by standing on chairs, in a hanged posture. The characters are Sidney Johnson (Gregory Fenner), Hayes Turner (Ronald L. Conner), and his wife, Mary Turner (Tiffany Addison), three of more than a dozen people lynched in 1918 in Lowndes County, Georgia. Having been in this holding area for an indeterminate amount of time, Hayes is ready to move on to the better part of the afterlife, but Mary doesn’t understand that she’s dead, and is still haunted by the cries of their baby. The room they’re in currently is under the control of hostile, demonic forces who have fixed things so that Mary can see Sidney, but not Hayes, and the two of them have to purge each other of the ignorance and malice still keeping them here.

Sidney’s more than a little concerned that Mary’s going to blame him for their being in this mess. Having been sentenced to jail for gambling, Sidney became indebted to Hampton Smith, a particularly brutal plantation owner, and worked off the price of his fine many times over. But the plantation owner refused to let him go, and Sidney, fed up with injustice, proposed killing him to Hayes and Mary. He had reason to approach them; Hayes had spent time on a chain-gang for hitting Smith in defense of Mary, but the couple, who had two children and another due in a month, told him that for families, survival comes first. Bitterly disappointed, Sidney killed Smith anyway, prompting the massacre of Lowndes County’s black population in retaliation. To hear it described that way, it sounds very dry, but the ghosts need to remember the details of both the murders and their feelings about what happened beforehand to work through their confused state of mind.

The three actors give masterful performances both as spirits in various states of existential crises, and as living people, still planning for a future. Addison’s eyes are wonderfully expressive; blame, courage, pleading, and despair all shine from them at different moments. Between time shifts, Fenner switches rapidly between directing his rage outwards and inwards, and his close connection with the other actors allows him to build and lower Sidney’s passions smoothly. Conner plays the oldest character, who is wise enough to know he has little control over anything but himself, but is an optimist even in Purgatory, where he does what he can to guide his wife and friend. The three are heart-wrenching, and while Dalcoe’s dialogue is on occasion a little blunt and didactic, the actors make it all plausible for their characters.

Director Harry Lennix has not shied away from making A Small Oak Tree Runs Red very difficult to watch. As gruesome as the news reports Dalcoe includes are, the demonic influence represented by the design team is almost worse. Sound designer Brandon Reed has supplied the horrific jeers of the mob, which still torment the characters, and ratchet up in volume and viciousness when they violate the purgatory’s rules. Samantha C. Jones’s costumes are adjustable so the actors can suddenly become injured, return to their healthy status at an earlier point in the play, and then be covered in phantom wounds again. As I heard descriptions of historical lynchings while immersed in a design that’s meant to put the audience in the place of the victim, I remembered having felt cold and light-headed during a performance of Parade and I wonder if Congo Square’s African-American regulars might have a similar experience at this far more brutal show, despite its redemptive message. A Small Oak Tree Runs Red’s disturbing imagery makes it very much not for everyone, but it is transformative, and serves an important purpose in reminding us of the events that shaped our country.

Highly Recommended

Jacob Davis

Reviewed June 4, 2016

This show has been Jeff recommended.

For more information, see A Small Oak Tree Runs Red’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing at the Athenaeum Theatre, 2936 N Southport, Chicago. Tickets are $19.50-37.50; to order, call 773-935-6875 or visit CongoSquareTheatre.org. Performances are Thursdays-Fridays at 7:30 pm, Saturdays at 2:00 pm and 7:30 pm, and Sundays at 2:00 pm through July 3. Running time is two hours and ten minutes with one intermission.