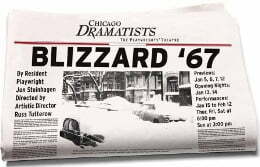

Blizzard ’67

Directed by Russ Tutterow

At Chicago Dramatists, Chicago

Dark comedy depicts human reactions to a life-altering blizzard

Jon Steinhagen, actor, playwright, composer, pianist, is a Chicago treasure. His impact on the theatre scene is immense whether he’s acting, accompanying or writing. His latest work, Blizzard ’67 now in its world premiere at Chicago Dramatists, is a gem of a dark comedy depicting the horrific snow blizzard of 1967 and the survival antics of four car-pooling Loop coworkers.

We meet the four fully developed characters, not friends, but car-pooling coworkers for a large Loop corporation. There is Landfield (John Gawlik) – a cynical, married, and frustrated corporate functionary stuck with a junky ’63 Ford Falcon and a unhappy marriage: he drinks too much.

Next there is Bell (Andy Hager) – a whining corporate survivor who goes along to get along. He is cowardly, jaded and pessimistic. He is also unfriendly.

Young Emery (Andy Lutz) is the ambitious junior executive, married, impressionistic, sensitive, insecure, and immature. He is outmatched by the three corporate veterans.

Lastly, Henkin (Stephen Spencer) the the razor-sharp, highly confident and obnoxious coworker who viciously snips at each of his fellow car-poolers. He is single and carefree from the family burdens that way so heavily on the other three. When he flaunts his recent purchase of a ’67 Chevy Caprice, the others realize that he got a promotion.

Lanfield is envious and upset that he didn’t get the promotion; Emery seeks tactical knowledge of how Henkin move up the corporate latter. Bell is resigned and content with his position on the corporate ladder. Playwright Steinhagen cleverly develops each sad, yet humorous, character that populated the stagnate corporate work of the ’50- ’60’s. We quickly laugh and empathize with this foursome making their adventures in the Blizzard of ’67 believable.

Once the snow starts, Landfield puts chains on his tires (remember chains?) so that he’ll be able to drive through snow. The snow keeps coming – more than an inch an hour. The four call each other wondering if they’ll be sent home early. They are given the opportunity to stay at a hotel in the Loop but they choose to make the journey home. Chaos ensues as the white-out snow slows their journey producing survival fears and anxieties.

Many of us have memories of that ’67 blizzard and the larger one in ’79 so we easily relate to the situations these four will encounter.

As the all day snow continues, the roads are littered with stalled cars, an empty bus and the inability to know their location increases the tension and the fear for each car-pooler. When Henkin bravely leaves the car to see what has happened in front of them to a stalled car, chaos ensues. The play takes a dark turn as each car-pooler struggles to survive and control his own apprehensions. Their survival is clouded with guilt and worry. The four players were outstanding. I particularly was impressed with Stephan Spencer who also deliciously played a woman and a little girl as well as Henkin. John Gawlik and Andy Hager were excellent as the corporate losers while Andy Lutz was hilarious at time as the neuritic young worker.

Steinhagen’s plot twists produce both humorous situations and reactions as well as truthful human actions based on each character’s personality. The characters dealing with a natural disaster tests their frail bond leading to plausible conclusions that become life altering consequences.

Blizzard ’67 is much more that a snow storm comedy, more that a quirky satire of ’60’s corporate types. It is a honest look at how four men deal with unforeseen chaotic events. Their personalities, warts and all, dictate their actions. Besides being a engaging theatre piece, Blizzard ’67 is a poignant study into the nature of human reactions – guilt and self-preservation dominant. This is Steinhagen’s finest work to date. Don’t miss this quirky gem. It is worth battling a snow storm to see.

Highly Recommended

Tom Williams

Talk Theatre in Chicago podcast

For more info checkout the Blizzard ’67 page on Theatreinchicago.com

At Chicago Dramatists, 1105 W. Chicago Ave., Chicago, IL, www.chicagodramatists.org, tickets $32, student tickets on Thursdays at $15, Thursdays thru Saturdays at 8 pm, Sundays at 3 pm, running time is 2 hours with intermission, through February 12, 2012

Another Review of Blizzard ’67 by Clint May

Chicago weather and the world of business have a lot in common. This is especially true in the winter months, and it is the infamous Chicago blizzard of 1967 that provides the allegorical backdrop to this Jon Steinhagen debut play directed by Russ Tutterow. Snowfall buries—even as it uncovers—the secrets of four businessmen at various stages in their careers whose disparate lives intersect in a cataclysm that rarefies their quiet desperation.

Lanfield, Henkin, Emery and Bell (John Gawlik, Stephen Spencer, Andy Lutz and Andy Hager) are the given-nameless suits carpooling to an undefined job in the Loop in the waning days of the American Dream. Encroaching disillusion in the corporate system hasn’t stopped young upstart Emery from dreaming he will follow in his father’s footsteps and climb the ladder of success. Fearfulness and resignation has kept sad-sack Bell firmly in a constipated limbo. Nameless yearning has driven Lanfield into fits of drinking and anger. Unfettered ambition and a lack of “anchors” has pushed Henkin into the upper echelons of the corporate world. It is Henkin’s seemingly ineffable promotion that creates a schism in the carpool quartet that drives them all to question their place in a world where even one’s seat in the car denotes status. Like primitive men attempting to augur the will of unseen gods, the remaining three must figure out what it is that will appease their hidden masters that they too might be allowed an ascension.

“Cold” on the heels of a early-winter hot-flash of 65°, the great blizzard takes the four men at work by slow surprise as it grows from a predicted four inches to a monstrous two feet. Unease and panic quickly follow, as hasty decisions must be made as to what is to be done: try to brave the madness outside, or take refuge in a company-billed hotel. Upon seeing the merits of an easily-forgiven snow-day should they make it back to their northwestern suburban homes, the group decide to brave the elements but make it no farther than the river before realizing the enormity of their mistake. The blizzard is drowning the city, and any knowledge of where they are is being obliterated as they crawl down barely seen streets.

It is here that they happen upon a mysteriously stranded car. Henkin, perhaps eager to display bravado after a dressing-down by his former contemporaries-cum-lackeys, gallantly offers to help the invisible stranded motorist despite the protests of his carmates. As the remainder squint and squirm, they believe they hear Henkin gunned down, and in a blind panic, race away from the scene in a bid for self-preservation.

Here the tone of the play begins to ease from sitcom to tragedy, as Lanfield, Emery and Bell must now come to terms with what they believe to be a crime they just witnessed, but one which they can’t fathom how to report. They are bonded to protect the secret of their cowardice. What ensues in the aftermath is a touching series of vignettes in the lives of these seemingly average men as each attempts to reconcile what they saw and did into their unremarkable lives. Emery conceives a son that very night in a life-affirming fit of copulation. Bell touchingly connects to his son’s innocent desire for play and wonder. Lanfield opens up to his wife in what we must assume is a first-time event.

The final mystery of what happened to Lenkin is resolved only for one as he becomes one of the casualties of the blizzard, dying a small and meaningless death in the snow, another victim of a heart attack brought on by over exertion. It’s a fitting end, and the two remaining take the stage for one last time to narrate the sad truths that became their lives. Each speaks to their death: one quick, and one taken in small measures.

Well-cast to a piece, the troupe sympathetically inhabits these men’s tiny lives. Special attention must be given to Stephen Spencer as Henkin, who performs multiple roles in rapid succession when the guilt-ridden consciousness of each man puts Henkin in place of the faces of loved ones (none more mournfully than Lanfield’s sympathetic wife).

It’s a tragicomedy for the modern era that asks each of us how we live with things we never thought we’d do when faced with extraordinary circumstances. The true chill comes not from the snow, but from a stinging reminder that we may only be as good as the places we find ourselves. Behind each life lived long enough is a landscape made unrecognizable, with sins and hopes alike reduced to mere mounds under the inexorable accumulation of time.

Highly Recommended.