Far From Heaven

Book by Richard Greenberg

Music by Scott Frankel

Lyrics by Michael Korie

Directed by Rob Lindley

Musical Direction by Chuck Larkin

Produced by Porchlight Music Theatre, Chicago

50s Social Conflict with Meditative Music

Todd Haynes’s 2002 movie Far From Heaven was intended to be an homage to melodramatic 50s soap-opera-like movies. So when Richard Greenberg and Scott Frankel adapted it for the stage in 2013, using slow, atonal music instead of dramatic melodies was a bold choice. Which is not to say that it was a successful one. Greenberg’s book sticks closely to the movie, and in Porchlight Music Theatre’s Chicago premiere, several actors, including Summer Naomi Smart, give intelligent, well-crafted performances. But this story doesn’t feel like it benefits from being a musical, which is unfortunate, because melodramas depend more on their music for emotional impact than on how well actors convey broadly-drawn characters.

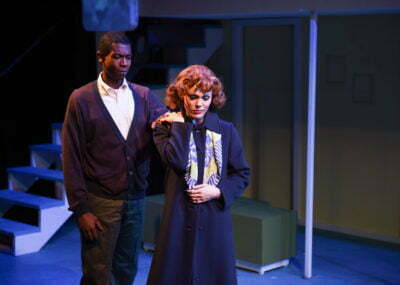

Cathy Whitaker (Smart) is a housewife in 1957 Hartford whose life is everything she had believed constituted “good.” She’s part of the resurgent middle class, her husband Frank (Brandon Springman) has an office job, she has a dutiful black maid, her kids…are a little annoying, actually, but not screwed up in any major way. But then her social status unravels in bizarre ways. Frank starts getting harassed by the police for no apparent reason Cathy can see. That doesn’t prevent a local gossip from interviewing Cathy for a human-interest story to show how respectably uninteresting she is, but during the interview at her house, Cathy sees a strange black man in the yard, and shouts at him. The man, Raymond Deagan (Evan Tyrone Martin), is the son of the groundskeeper, who died suddenly. Cathy’s apology and expression of condolences gets her written up in the rag as a woman who is “nice to negroes,” and her friends start not-so-nicely teasing her for being a radical. Cathy is also surprised while talking to them to learn that it is normal for men to keep having sex with their wives after they have children.

One day, after feeling weird about her nascent friendship with Raymond and guilty over keeping her maid from her own family, Cathy goes to Frank’s work to deliver his dinner, and finds him kissing another man. It seems Frank regularly goes cruising the streets, but this time, found a man at the office in a similar situation to himself. Cathy is understandably hurt and insists that Frank undergo conversion therapy, and he agrees to, even though his psychologist outright tells him that it won’t work. It doesn’t, and their relationship declines in an ugly manner. Cathy’s friendship with Raymond is also blossoming, which invites hostility from both the black and white sides of town. After Frank humiliates her at a party, Cathy suggests a vacation will help solve their problems, but that doesn’t work, either.

From the plot description, these characters don’t sound that wonderful, but Smart, Springman, and Martin sell their various conflicts. They’re products of their environment, but also trying to break free from it. Cathy is an especially reserved woman, and therefore somewhat resilient to social pressure. But she’s mostly passive, not a visionary, and doesn’t seem to have much exposure to other ways of thinking. Smart has mastered Frankel’s difficult score, and her opening song “Autumn in Connecticut” is one of the show’s highlights. Another strong piece of music is Springman’s second act “I Never Knew,” which encapsulates the whole show’s themes. Bri Sudia also gives a strong dramatic performance as Cathy’s friend Eleanor, who can see the problems lurking beneath the idyllic suburban life more clearly, but is not quite an ally. Chuck Larkin, as conductor and musical director, has assembled a large ensemble for the many chorus scenes, who perform what is written for them very well.

It is possible that Frankel’s music didn’t come through at its full potential at the performance I attended because the speakers were placed in the audience’s walk-way and were in sorry condition by the time the second act started. But his style is still a very particular taste which doesn’t do a whole lot to elevate Far From Heaven’s social issue soap-opera content, although playing it straight as melodrama may have been worse. Bill Morey’s costume designs are colorful and fun, but Grant Sabin’s sarcastic scenic design, which sets the play in a rudimentary doll house, lacks the superficial charm of Eisenhower suburbia, and the show doesn’t compare favorably with Ibsen. Far From Heaven checks off the full list of 50s social evils, but at this point of removal, without dynamic characters and dialogue, it’s hard to care a whole lot. Fans of the movie may still enjoy it, though, and fans of this kind of music will admire Smart’s voice.

It is possible that Frankel’s music didn’t come through at its full potential at the performance I attended because the speakers were placed in the audience’s walk-way and were in sorry condition by the time the second act started. But his style is still a very particular taste which doesn’t do a whole lot to elevate Far From Heaven’s social issue soap-opera content, although playing it straight as melodrama may have been worse. Bill Morey’s costume designs are colorful and fun, but Grant Sabin’s sarcastic scenic design, which sets the play in a rudimentary doll house, lacks the superficial charm of Eisenhower suburbia, and the show doesn’t compare favorably with Ibsen. Far From Heaven checks off the full list of 50s social evils, but at this point of removal, without dynamic characters and dialogue, it’s hard to care a whole lot. Fans of the movie may still enjoy it, though, and fans of this kind of music will admire Smart’s voice.

Somewhat Recommended

Jacob Davis

3jacob.davis@gmail.com

Reviewed February 12, 2016

This show has been Jeff recommended.

For more information, see Far From Heaven’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing at Stage 773, 1225 W Belmont Ave, Chicago.