Looking Over the President’s Shoulder

By James Still

Directed by Timothy Douglas

Produced by American Blues Theater

Playing at the Greenhouse Theater, Chicago

How to Succeed at Becoming Your Job

A common fear among young artists is that their survival jobs could wind up overtaking their aspirations. The irony is that a survival job doesn’t even have to be degrading to cause this kind of anxiety; it could even be something that, for other people, would seem highly desirable. Take, for example, the case of Alonzo Fields, the subject of James Still’s one-man play Looking Over the President’s Shoulder. Born in 1900 in the all-black town of Lyles Station, Indiana, this classically trained opera singer practically fell into the job of chief butler at the White House for twenty years. In a sensitive and captivating performance, Manny Buckley as Fields relates how he was witness to some of the most momentous events of the twentieth century and was the confidant of presidents, but never got to do what he really wanted.

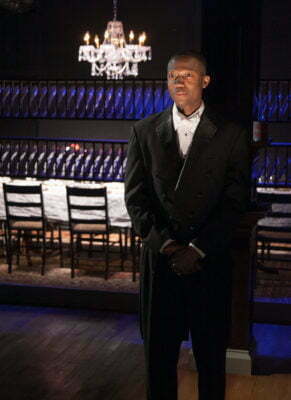

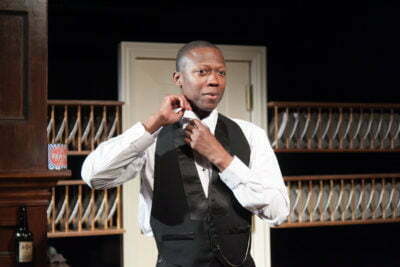

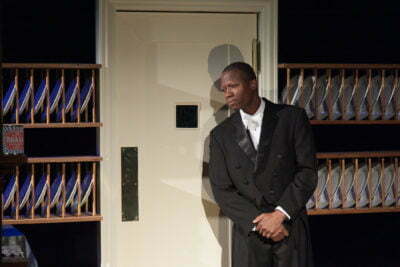

When we first see Fields, he describes the White House as well as any tour guide would, and pays careful attention to its construction by African-American slaves and freemen. Brian Sidney Bembridge’s scenic design sets Fields amid a long rack of plates, with a dining room visible in the background, just as in his job, Fields could see without being seen. He has just quit. The year is 1953; he has been in service since 1931, head butler since 1933, and wants to move on. He is a little wistful. Fields was a very good butler, and he did come to see his job as important. It certainly supported his family. Now, he decides, he can finally tell his story, after having been required to stay silent for so long.

Growing up insulated from white racism in an all-black town gave Fields a sense of confidence in himself. He ran a grocery store, and during the Great Depression, moved to Cambridge to work as a butler to an MIT professor while learning Italian, French, and German. Proximity to the elite while he attended a conservatory would be good for his music career, he figured, and the economic situation being what it was, it was good to have any job at all. Serving first lady Lou Hoover at a luncheon one day was mildly interesting, but he didn’t think anything more of it until his employer died suddenly. He was surprised Mrs. Hoover remembered him, and offered him a job at the White House. It was only supposed to last a year, but at the end of that year, no further opportunities had come along. Then Mr. Hoover lost re-election, Fields alone out of all the servants was able to communicate with the new first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, and he got his historic promotion, making him the first African-American White House chief butler. He probably wouldn’t have taken the job if not for his family, but he figured Roosevelt wouldn’t be president forever.

As Fields, Buckley constantly has to negotiate between bitterness and reminding himself to see the good in what he had. The Roosevelts were much more personable than the Hoovers, and Fields found that he didn’t hate his job. Being a manager for the first time since he ran the grocery store allowed him to exercise his intellect, and occasionally, his creativity. We see the awe in Buckley’s face as he describes being present when Roosevelt was informed of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and the awareness that he was witnessing history. He proudly shares humorous anecdotes about everyone from Errol Flynn to Winston Churchill, the deeply touching experience of hearing George VI speak, and his sorrow at Roosevelt’s death. But happiness working for him was always complicated and fleeting. When Roosevelt nominated Klansmen Hugo Black to the Supreme Court, Fields bit his tongue and ordered the younger black men on staff to do the same. Buckley’s contorted face and unusually soft voice while telling that story betray a deep-seated pain and humiliation that recurred too often to be alleviated much by time.

As Fields, Buckley constantly has to negotiate between bitterness and reminding himself to see the good in what he had. The Roosevelts were much more personable than the Hoovers, and Fields found that he didn’t hate his job. Being a manager for the first time since he ran the grocery store allowed him to exercise his intellect, and occasionally, his creativity. We see the awe in Buckley’s face as he describes being present when Roosevelt was informed of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and the awareness that he was witnessing history. He proudly shares humorous anecdotes about everyone from Errol Flynn to Winston Churchill, the deeply touching experience of hearing George VI speak, and his sorrow at Roosevelt’s death. But happiness working for him was always complicated and fleeting. When Roosevelt nominated Klansmen Hugo Black to the Supreme Court, Fields bit his tongue and ordered the younger black men on staff to do the same. Buckley’s contorted face and unusually soft voice while telling that story betray a deep-seated pain and humiliation that recurred too often to be alleviated much by time.

Fields never comments on Black’s tenure on the court, and the one frustrating feature of the play is how much isn’t there. In fairness, twenty-one years plus his life before the White House is a lot to cover in ninety minutes, and anything other than a one-man show would likely have again reduced Fields to the role of silent observer. Fields found some peace at the White House under Harry Truman, who he felt truly valued him as an equal, but by then, we’re well into the third quarter of the play. Fields remained the head butler until early in Eisenhower’s administration, and implies the burden of having to learn a new family’s habits, the prospect of having to be in close proximity to Richard Nixon, and the absence of any economic crises or world war dissuaded him from continuing on. We get glimpses into his relationships with each of the people he served, and anecdotes which are no less interesting for being somewhat scattershot. Buckley’s performance and Timothy Douglas’s direction present us with an intriguing, fully-formed character. Though we understand the reason for his ambivalence fairly early, he’s good company, and likely to inform us of some things we don’t already know.

Fields never comments on Black’s tenure on the court, and the one frustrating feature of the play is how much isn’t there. In fairness, twenty-one years plus his life before the White House is a lot to cover in ninety minutes, and anything other than a one-man show would likely have again reduced Fields to the role of silent observer. Fields found some peace at the White House under Harry Truman, who he felt truly valued him as an equal, but by then, we’re well into the third quarter of the play. Fields remained the head butler until early in Eisenhower’s administration, and implies the burden of having to learn a new family’s habits, the prospect of having to be in close proximity to Richard Nixon, and the absence of any economic crises or world war dissuaded him from continuing on. We get glimpses into his relationships with each of the people he served, and anecdotes which are no less interesting for being somewhat scattershot. Buckley’s performance and Timothy Douglas’s direction present us with an intriguing, fully-formed character. Though we understand the reason for his ambivalence fairly early, he’s good company, and likely to inform us of some things we don’t already know.

Recommended

Jacob Davis

[email protected]

Reviewed February 11, 2016

This show has been Jeff recommended.

For more information, see Looking Over the President’s Shoulder’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing in the Upstairs Studio at the Greenhouse Theater Center, 2257 N Lincoln Ave, Chicago. Tickets are $29-39, with discounts for students, seniors, and groups; to order, call 773-404-7336 or visit AmericanBluesTheater.com. Performances go through March 6. Running time is ninety minutes with no intermission.