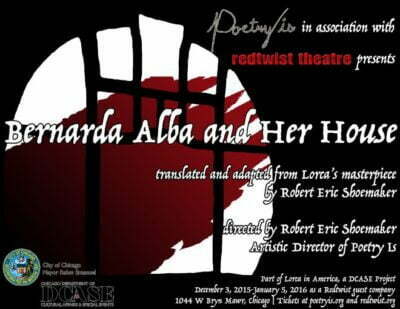

Bernarda Alba and Her House

Translated and Adapted from Federico García Lorca

Translated and Adapted from Federico García Lorca

Directed and Adapted by Robert Shoemaker

Produced by Poetry Is

Playing at Red Twist Theatre, Chicago

A Southern Gothic Treatment of Spain

No matter how bravely theatre artists praise limited resources and for spurring creativity, it’s still always a relief to see productions that are heavily shaped by circumstance and necessity succeed in practice. So it is with Bernarda Alba and Her House, a project by Lorca expert and Poetry Is artistic director Robert Shoemaker, who has previously garnered praise, including mine, for his two-person chamber musical Plath/Hughes. This new adaptation is supported by the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events as part of Shoemaker’s interest in transplanting Lorca stories to the United States, as well as by Red Twist Theatre, which is hosting the production as part of a year-old program in which the small but artistically magnificent non-Equity company contributes its storefront space to another company. Currently, Red Twist’s theatre is arranged with just two rows of seats on opposite walls with benches in the middle for its recently-extended production of Incident at Vichy, Arthur Miller’s psychological examination of a group of men who have been arrested by Nazi collaborators. The use of the same arrangement for an all-female play about isolation and repression authored by the most famous victim of Spanish fascism makes for an appropriate companion piece, in addition to the production’s own considerable strengths.

Shoemaker’s adaptation moves La Casa de Bernarda Alba to Louisiana, and gives the characters American names (Bernarda Alba/Bernadette Talbot-White, Angustias/Augustina, Martirio/Martha, Adela/Adelaide, etc.). Other than that, and being pared down to ninety minutes, the text of the production is quite faithful. The second husband of the staunchly conservative Catholic Bernadette (Sara Stern) has died, and Bernadette is now strictly enforcing an eight-year long period of mourning on her household. For her five adult daughters, who range in age from twenty (Adelaide, played by Elaine Small), to thirty-nine (Augustina, played by Stacie Hauenstein), that means no leaving the house, or talking to men, although since Augustina was Bernadette’s daughter from a previous marriage, she is still allowed to talk to meet her fiancé at the window. Those window assignations are pretty much the only socially acceptable way for the sexes to interact in the sexually repressed little town. Although prostitutes and other “bad women” sometimes pass through to service the young men of the lower classes, Bernadette, who is only wealthy by small-town standards, insists on holding her daughters above the riff-raff. However, Adelaide and her full-sister, Martha (Gilly Guire), are jealous of Augustina, and can see that her boyfriend only wants her for the fortune she’s inherited from her father. As Adelaide attempts to conceal her own affair, the house members turn on each other in angry, desperate frenzy.

Shoemaker’s adaptation moves La Casa de Bernarda Alba to Louisiana, and gives the characters American names (Bernarda Alba/Bernadette Talbot-White, Angustias/Augustina, Martirio/Martha, Adela/Adelaide, etc.). Other than that, and being pared down to ninety minutes, the text of the production is quite faithful. The second husband of the staunchly conservative Catholic Bernadette (Sara Stern) has died, and Bernadette is now strictly enforcing an eight-year long period of mourning on her household. For her five adult daughters, who range in age from twenty (Adelaide, played by Elaine Small), to thirty-nine (Augustina, played by Stacie Hauenstein), that means no leaving the house, or talking to men, although since Augustina was Bernadette’s daughter from a previous marriage, she is still allowed to talk to meet her fiancé at the window. Those window assignations are pretty much the only socially acceptable way for the sexes to interact in the sexually repressed little town. Although prostitutes and other “bad women” sometimes pass through to service the young men of the lower classes, Bernadette, who is only wealthy by small-town standards, insists on holding her daughters above the riff-raff. However, Adelaide and her full-sister, Martha (Gilly Guire), are jealous of Augustina, and can see that her boyfriend only wants her for the fortune she’s inherited from her father. As Adelaide attempts to conceal her own affair, the house members turn on each other in angry, desperate frenzy.

Lorca used the concept of duende to describe irrational, morbid emotions evoked by the flamenco, surrealism, puppet-theatre, and folklore he was fascinated by. However, his last play, Bernarda Alba, was a major shift for him stylistically. Lorca stated in the script that the play was meant as a “photographic document.” Shoemaker ignores that instruction. Four dancers sit in the corner of the theatre, and accentuate the action with stomping, singing, musical instruments, and occasionally, joining in the scene to interact with Bernadette’s senile mother, Mary Jo (Nancy Wai). These non-naturalistic innovations massively increases the play’s emotional force in its confined quarters; for while intimacy can strengthen an audience’s connection to a particular character, Bernarda Alba is a large ensemble piece, and music (composed by Przemyslaw Bosak) charges the atmosphere with all the characters’ feelings at once. At one point in the story, there is an off-stage lynching. This moment could have easily gone awry if staged realistically, but in the shadowy, nightmarish world build mainly on imagination, it is much more frightening.

Lorca used the concept of duende to describe irrational, morbid emotions evoked by the flamenco, surrealism, puppet-theatre, and folklore he was fascinated by. However, his last play, Bernarda Alba, was a major shift for him stylistically. Lorca stated in the script that the play was meant as a “photographic document.” Shoemaker ignores that instruction. Four dancers sit in the corner of the theatre, and accentuate the action with stomping, singing, musical instruments, and occasionally, joining in the scene to interact with Bernadette’s senile mother, Mary Jo (Nancy Wai). These non-naturalistic innovations massively increases the play’s emotional force in its confined quarters; for while intimacy can strengthen an audience’s connection to a particular character, Bernarda Alba is a large ensemble piece, and music (composed by Przemyslaw Bosak) charges the atmosphere with all the characters’ feelings at once. At one point in the story, there is an off-stage lynching. This moment could have easily gone awry if staged realistically, but in the shadowy, nightmarish world build mainly on imagination, it is much more frightening.

Just as thick as the atmosphere of dread is that of repressed sexuality. Sara Stern is remarkably human in the title role. She gets turned on when her servant, Cindy (Lauren Miller), describes the escapades of the gleaners, and is weirdly insistent on being naïve about her daughters’ jealousy until there’s proof of Adelaide’s affair. When she tells Augustina to let her husband keep secrets, she says so with such urgency that it is clear how, in her misguided way, she wants what is best for her daughters. That doesn’t make her any less terrible, but the other actresses have a lot to play off of. Gilly Guire as Martha is delicately passive-aggressive, while Elain Small’s Adelaide is belligerently self-justifying, both making fine use of Louisiana accents. All of the sisters are perpetually agitated, and besides being starved for sex, are cooped up with too many people and constantly on edge from lack of privacy. Shoemaker’s concept allows all the inhabitants of Lorca’s play to be sympathetic, while tragically flawed, and finds some beautiful stage pictures while doing so. Though the production’s limited resources occasionally reveal themselves when a staging idea isn’t fully fleshed out, this adaptation preserves and delivers the emotional core of what makes The House of Bernarda Alba such a fascinating character study, with a unique twist.

Just as thick as the atmosphere of dread is that of repressed sexuality. Sara Stern is remarkably human in the title role. She gets turned on when her servant, Cindy (Lauren Miller), describes the escapades of the gleaners, and is weirdly insistent on being naïve about her daughters’ jealousy until there’s proof of Adelaide’s affair. When she tells Augustina to let her husband keep secrets, she says so with such urgency that it is clear how, in her misguided way, she wants what is best for her daughters. That doesn’t make her any less terrible, but the other actresses have a lot to play off of. Gilly Guire as Martha is delicately passive-aggressive, while Elain Small’s Adelaide is belligerently self-justifying, both making fine use of Louisiana accents. All of the sisters are perpetually agitated, and besides being starved for sex, are cooped up with too many people and constantly on edge from lack of privacy. Shoemaker’s concept allows all the inhabitants of Lorca’s play to be sympathetic, while tragically flawed, and finds some beautiful stage pictures while doing so. Though the production’s limited resources occasionally reveal themselves when a staging idea isn’t fully fleshed out, this adaptation preserves and delivers the emotional core of what makes The House of Bernarda Alba such a fascinating character study, with a unique twist.

Recommended

Jacob Davis

Playing at Red Twist Theatre, 1044 W Bryn Mawr, Chicago.