Carlyle

By Thomas Bradshaw

By Thomas Bradshaw

Directed by Benjamin Kamine

Produced by Goodman Theatre, Chicago

What’s Onstage is Only the Tip of the Satirical Iceberg

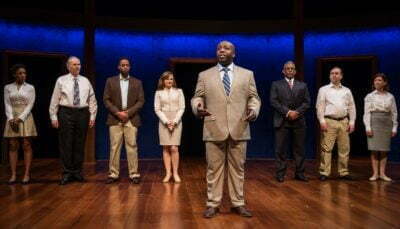

Local playwright Thomas Bradshaw has gained a reputation for being something of a professional troll. But in Carlyle, now in its world premiere at the Goodman, Bradshaw uses his ability to offend to create uproarious political satire. This is the story of how a black man becomes a member of the Republican Party, as told by himself in a fourth-wall-breaking performance with his friends and family. The point of Carlyle/Bradshaw’s jibes are often frustratingly elusive, for Bradshaw often uses Carlyle to make a reasonable, although well-agreed upon point, only to make him look ridiculous immediately afterward. But it is a play which provides great amusement to the audience, as well as plenty of occasions for nervous glances to their neighbors.

Carlyle Myers (James Earl Jones II) is first seen in a video from the Goodman’s dressing rooms, in which he frets to his wife, Janice (Tiffany Scott), over the hostile response he anticipates from the liberal theatre audience. But she reassures him that he’s attractive and charming, and he arrives onstage nervous, but determined to fulfill his mission of explaining himself to us. Carlyle was born in Greenwich, Connecticut, and was raised by his wealthy widowed father (Tim Edward Rhoze). For a while the only black student at his elite private school, Carlyle first became aware of race as a teenager, when students from the ghetto were brought in as part of a ham-fisted attempt at integration (the kind Antonin Scalia called “mismatching”). These students made Carlyle ashamed of being a sell-out, and he briefly sought to emulate them, but their failures and expulsion, along with some tough love from his friends and father, set him back on the path to the Ivy League.

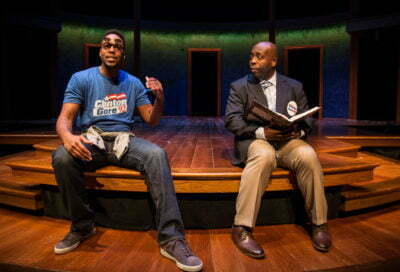

At Harvard, Carlyle’s opinion of affirmative action further deteriorated. He joined the 1992 Clinton/Gore campaign, but got into an argument with his black roommate about whether it made sense to consider race an advantage or disadvantage without regard to class, and about the existence of black slaveowners and the relative scarcity of slaveowners in general compared to the nineteenth century population. For these departures from leftist orthodoxy, he was expelled from the campaign, and with the guidance of his conservative father and new girlfriend, he quickly wound up on the side of the Republicans. This is the segment of the show which is treated the most realistically, and while it’s a good illustration of how somebody could become disillusioned with campus radicals, I find it insufficient to explain why someone would become a Republican. In the first place, radical leftists would never work for Bill Clinton. When they vote at all, it’s usually for third party candidates. Furthermore, Carlyle’s opinion that affirmative action should advantage rural and rust-belt white kids over upper-middle-class African-Americans and children of African immigrants has been explicitly endorsed by Barack Obama, while Republicans usually oppose class-based affirmative action as stridently as when it is race or gender-based.

As Carlyle goes into other reasons for being a Republican, his presentation becomes steadily more bizarre. Bradshaw’s humor is at its finest and most obscene in the latter portion of the play, and audience members at the opening got riled up more than usual. Some of them were plants who bowed at the end of the performance, but some weren’t, or at least, weren’t revealed. The fun and the danger of the show is seeing how the people around you will respond to Carlyle’s bashing of Anita Hill, and his claim that the way to prevent unarmed black men from being gunned down is to require everybody to always be armed.

James Earl Jones II leads the entire cast in genial performances, and director Benjamin Kamine further sharpens the text’s satire (as does work from Kevin Depinet, Rachel Healy, Heather Gilbert, and Christopher Kriz on the design team which would make sketch comedy theatres proud). He, Jones, and Bradshaw are clearly on the same wavelength. A difficulty of the play is that, at the time when the rift between the Republican Party establishment and its base is wider and more obvious than ever, Carlyle seems to represent both. His personality is reminiscent of Michael Steele’s, and he claims to be a counter to Donald Trump, but the things he says out loud are often just as outrageous. Whether Bradshaw is making a point about the Republican leadership, or despite his desire to present a balanced perspective, just couldn’t find anything remotely sympathetic in the conservative platform other than fixing affirmative action, is open to interpretation. But the results will have most audience members laughing and cringing in equal measure, and perhaps, learning more than they thought they wanted to.

Recommended

Jacob Davis

Reviewed April 11, 2016

For more information, see Carlyle’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing in the Owen Theatre at the Goodman, 170 N Dearborn, Chicago. Tickets are $10-40; to order, call 312-443-3800 or visit GoodmanTheatre.org. Performances are April 19 at 7:30 pm, Wednesdays at 7:30 pm, Thursdays at 7:30 pm, Fridays at 8:00 pm, Saturdays at 2:00 pm and 8:00 pm, and Sundays at 2:00 pm and 7:30 pm through May 1. (no evening performance April 17 and May 1). Running time is seventy-five minutes.