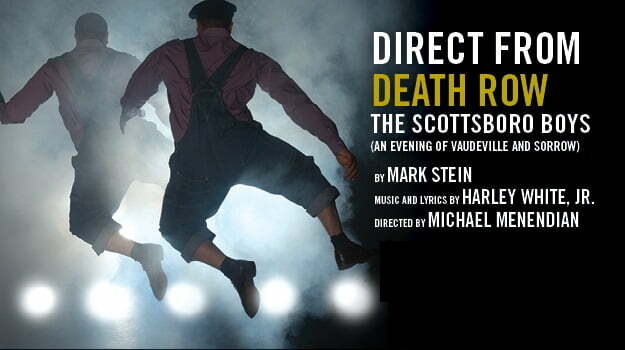

Direct from Death Row The Scottsboro Boys – Remount

(An Evening of Vaudeville and Sorrow)

By Mark Stein

Music & Lyrics by Harley White, Jr.

Directed by Michael Menendian

Musical Direction by Frederick Harris

Choreography by Kat Dennis

Produced by Raven Theatre Company, Chicago

“The truth will stain, while a lie will fall.”

A Hysterical Yet Poignant Retelling of an American Tragedy of Justice

After its award-winning run in the fall, Direct from Death Row The Scottsboro Boys returns to Raven Theatre for the next six weeks for an encore engagement featuring the entire original cast who won for “Outstanding Ensemble” at the Non-Equity Jeff Awards. And after witnessing this remount, I can tell why. True to its subtext, Direct from Death Row offers an evening of laughter, sorrow and everything in between, with gripping storytelling, masked satire, and impeccable performances that stir pathos just as well as laughter.

Under the misty haze and midnight-blue lights, nine black, young men, singing “Wade in the Water,” file in to literally set the stage for their retelling of the events that made them famously infamous as the “The Scottsboro Boys,” “second only to the circus as the greatest show on earth.” “Direct from Death Row The Scottsboro Boys (An Evening of Vaudeville and Sorrow)” is the name of their vaudevillian show, and for the next two hours they directly and theatrically tell us, their audience, their story with singing, dancing, and masked satire.

It all starts in 1931 with a confrontation on a freight train between two hoboing groups of young men, black and white. The confrontation soon escalates into an all-out racial brawl, and, after the white men flee the train, nine of the black men on the freight are arrested for assault. Later, however, in the holding cell, two white women are brought before the nine to be identified for another charge. What else exactly are they supposed to have done? The answer surprises them all: rape.

Thus begins a series of trials that spans over a decade, with interested parties stepping in and out of the ring as their self-interest or the puppeteers of justice dictate. Who is for these boys, truly? Is it the huckster-like Joe Brodsky (Breon Arzell), the Communist Party attorney, with his big talk of the boys being the scapegoat for an America-wide labor conspiracy? Or is it the idealist-apparent Walter White (Brandon Greenhouse), head of the NAACP, who believes effective social and political change can only be won within the system? Or, perhaps, is it the smiling slink Sam Leibowitz (Andrew Malone), criminal defense attorney extraordinaire, with his questionable practices and powerhouse of money? Are any of these sweet-talking men actually interested in justice? The answer, ultimately, seems doubtful as the last back-room deal is made and the blow of justice’s gavel gives its final (albeit “lenient”) report. But the lives of these nine boys (now, men) have been spent and tried in more ways than a court can appreciate. What’s left is merely the gradual dissipation of whatever spirit of life they have left, to be haunted (eternally, we discover) by the memories of actions they did not commit and the consequences over which they had no power.

The story of The Scottsboro Boys is not only the story of the corrupting power of racism in the course of justice — for which this story certainly has its contemporary appeal — but, moreover, it is the story of human greed — for notoriety, fame, power — masking (here, literally) as justice and ideals. Stein’s play pointedly (and ironically) gives the narrative voice to the nine wrongly accused, but the whole time the action of the play is progressed only by the white-masked do-gooders, each, we are shown, acting from impersonal (but not impartial) motives. In fact, the only effective actions the nine instigate in the play are those of violence and escape: their last recourse to exerting their individual freedoms.

That being said, having the white characters played in masks (made by David Knezz) is particularly effective for communicating this sense of “impersonality:” especially to these nine young men, these figures are less than sympathetic allies (and visa versa, one might add). The masked acting — amazingly conveyed through the physicality and vocal affectations of the actors — also adds a lot of humor (a lot). Andrew Malone definitely re-earns his Best Actor award, which he won at the Broadway in Chicago Awards this past year, with his hilarious dancing, jittering, and slinking performance as Leibowitz. Likewise, Breon Arzell’s masked transformation from the meek and quiet Willie Robinson to the boisterous trickster Brodsky is both hysterical and incredible: I still am in awe that he plays both characters.

Since the story is largely told as a direct-address to the audience and continuously shifts from satire to drama — two characteristics I typically have difficulty engaging with emotionally — I didn’t expect to be as emotionally stirred as I was at the end of the show. Yet, after two hours of living with these characters, witnessing their manipulation at the hands of the selfish powers of politics and fame, and experiencing their continually frustrated and sincere efforts to prove their innocence, I found myself helplessly embroiled in their emotional and psychological exhaustion. Again, I credit the power of the performances. In particular, Kevin Patterson, one of the few actors who does not have multiple roles, absolutely captivates and devastates in his final monologue as Haywood Patterson in which he details his escape from prison. A very powerful moment indeed.

Direct from Death Row The Scottsboro Boys tells an old (yet familiar) story in a strikingly unique way; and, speaking as one not fond of historical or racial stories, I think every theatregoer will find something to enjoy in this fantastic production (excepting children, obviously). Though there is a lot of factual information to digest throughout the play, the all-too-human story comes through in the fantastic acting, singing, dancing, and uproarious masked satire (though, be aware, this is not a “musical”). So even if you get lost in the sequence of trials or forget who did what when, one will likely find themselves effected one way or another.

Highly Recommended

August Lysy

Reviewed on 23 July 2016.

Playing at Raven Theatre’s East Stage, 6157 N. Clark St., Chicago. Tickets are $42 for general admission, $37 for seniors and teachers, and $18 for students and military. For tickets and information, call 773-338-2177, or visit RavenTheatre.com. Performances are Fridays and Saturdays at 7:30 p.m., and Sundays at 3:00 p.m. through August 27th. Running time is 2 hours and 15 minutes, with one 15-minutes intermission.