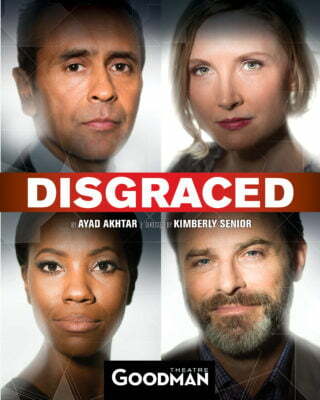

Disgraced

By Ayad Akhtar

Directed by Kimberly Senior

Produced by Goodman Theatre, Chicago

Co-Produced by Berkeley Repertory Theatre and Seattle Repertory Theatre

A Multicultural Doll’s House

Although the Goodman’s production of Ayad Akhtar’s Disgraced is something of a homecoming, the play having debuted only three years ago at American Theatre Company, the enthusiasm of the audience at the performance I attended proved that Chicago is still a long way from being saturated with this story. This year, the 2013 Pulitzer Prize winner is set to become the most produced play in the United States, and Akhtar’s companion piece, The Who and the What, made its Midwestern premiere at Victory Gardens a few months ago. Its popularity is due to the brutal frankness of its discussion of the huge number of political issues Akhtar presses into his drama of the New York City elite, most notably, how the place of Muslims in America exposes the superficial or contradictory nature of unsophisticated multiculturalism. However, this production, which is directed by Kimberly Senior, who also directed Disgraced’s debut and its run on Broadway, has elements which led me to wonder if the play has been widely misinterpreted as grimmer than it was meant to be.

We first see corporate lawyer Amir Kapoor (Bernard White) while he is posing in his lavish apartment (a wonderful set by John Lee Beatty) for a painting by his adoring wife, Emily (Nisi Sturgis). They had some sort of racial incident with a waiter the previous night, and Emily hopes that by painting Amir in the style of Diego Velázquez’s portrait of his black slave/assistant/friend Juan de Pareja, she can show the world Amir’s nobility. Amir doesn’t understand what the big deal is and thinks her request is weird, but is willing to go with it. He’s more hesitant about the next request his wife and nephew Abe (Behzad Dabu, who invented the role) make of him. Abe’s birth name is Hussein, but like Amir, he changed it to disguise his Islamic heritage (Kapoor is usually a Hindu or Sikh name). However, Abe still follows the religion, and his imam has been charged with financially supporting terrorism. He wants Amir to attend an upcoming hearing. Amir is reluctant; besides that it’s not his area of law, the firm partners he works for are all Jewish and one is a major Netanyahu backer, and Amir is no fan of Islam himself. But to please his family, he goes.

Amir’s worst fears are realized when a New York Times article misleadingly suggests he is one of the imam’s lawyers. However, there are more pressing matters. Emily has been painting geometric patterns inspired by Islamic architecture. A Jewish art curator, Isaac (J. Anthony Crane), is interested in exhibiting her work, though he warns they’ll have to navigate accusations of appropriation and orientalism. Emily responds that Islam is part of Western culture, and has universal themes. They plan a couples’ dinner, but things get worse for Amir as his bosses transfer their affections to his African-American co-worker, Jory (Zakiya Young), Isaac’s wife. The dinner erupts into arguments fueled by professional jealousies, a revelation of infidelity, and incompatible moral philosophies among the four participants. Emily and Isaac are bourgeois liberals, Jory winds up stating that after growing up in the ghetto, she’ll always prefer order over justice, and Amir, after detailing and denouncing the many violent, bigoted, and absurd teachings in the Quran, admits he’s still a little sympathetic to those who fight for them.

Akhtar arranged this group of characters to allow for maximum confluence of the personal and political. Their nastier statements and recollections drew big gasps from the audience, but their foibles also elicited laughter several times. All five characters are condescending and listen to each other mostly with the intent of gathering material for arguments, with Dabu’s Abe being only a little more receptive to suggestion, at least, the first time we see him. White’s Amir, however, is never happier than when he is lecturing people and poking holes in their comfortable visions of the world. Sturgis’s Emily really does come across as naïve and insensitive. Early in the play, in one of many subtle moments Senior slips in, Emily opens the door to admit someone while Amir is in the living room and not wearing trousers.

My companion found it totally unbelievable that Amir and Emily have ever had sex, and therefore, the play had no tension, because their marriage was a failure from the first scene. I wouldn’t go that far, though it’s a common opinion, but while watching them, I was reminded of Torvald and Nora Helmer from Ibsen’s A Doll’s House. She idolizes a man she doesn’t understand because she stereotypes him as valorous, he values her as a status symbol and has no respect for her intellect. On Wednesday and Thursdays, there are talk-backs with the actors, and at the one I attended, the cast expressed surprise that so many people describe Disgraced as “bleak.” “Isn’t the way the play ends a good thing for the characters?” they asked. The more I thought about it, the more I agree with them.

I’m not sure what it means that this production of Disgraced seems to be received a little differently from the ones, also directed by Senior, which established the play’s reputation. I suppose the cognitive dissonance among leftists caused by radical Islam superseding Arab socialism as the Muslim world’s leading anti-Western ideology makes the play harrowing for some people, and a drama that addresses that shift is therefore expected to be very dark in tone. And while the play seems sympathetic to Amir’s critiques of his native culture, it also points out injustices Muslims are subjected to, like intelligence services targeting people with vulnerable immigration statuses for recruitment as agents in sting operations. But I don’t think Amir’s repressed momentary excitement over terrorism indicates some incomprehensible evil in his soul. His parents were born in Punjab during the Partition, during which hundreds of thousands of people were murdered in religious riots; of course he struggles with misplaced revenge fantasies, which unlike Isaac, he owns up to, and unlike Jory, he is ashamed of. I wonder how much differently I would have perceived this play if I knew the artists saw it as an awakening and chance for enlightenment for their characters, instead of a straightforward downfall and warning, like All My Sons or the myriad other tragedies we’re accustomed to. Perhaps not presuming Disgraced’s genre will improve other peoples’ experience watching it, though personally, I find it compelling either way.

Recommended

Jacob Davis

This show has been Jeff recommended.

Playing in the Albert Theatre at the Goodman, 170 N Dearborn Ave, Chicago. Tickets are $25-94; to order, call 312-443-3800 or visit GoodmanTheatre.org. Performances are September 29 at 7:30 pm, Wednesdays at 7:30 pm, Thursdays at 2:00 pm (except October 8) and 7:30 pm, Fridays at 8:00 pm, Saturdays at 2:00 pm and 8:00 pm, and Sundays at 2:00 pm and 7:30 pm (no evening performances October 4 and 11) through October 25. Running time is ninety minutes with no intermission.