Dunsinane at Chicago Shakespeare Theater

By David Greig

Directed by Roxana Silbert

Produced by The National Theatre of Scotland,

the Royal Shakespeare Company,

and Chicago Shakespeare Theater

No Happily Ever After for Scotland

Shakespeare’s Macbeth pretty clearly divides violence into the demonic and anti-demonic. Popular for four hundred years and counting, the play has vastly overtaken the real life king it was very loosely based upon in the common imagination, and has become a parable for how greed and ego lead to personal disaster. In 2010, Scottish playwright David Greig revisited the old story to explore the ramifications of elites getting in trouble beyond their personal fortunes. The result was Dunsinane, a tragedy for two whole countries, which draws from Shakespeare and real Scottish history, but most of all from the modern wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The play begins comically. The Boy Soldier (Tom Gill), writes home to his mother in England about how excited he is to join the English expedition to oust Macbeth and restore the friendlier Dunkeld dynasty. He meets new friends, sees strange landscapes, and upon landing, his first training is an acting lesson in how to play a tree. It seems light-hearted, but it gets straight to a core theme of Grieg’s: that in this world, the Anglo-Saxons are not agrarians and have very little knowledge of the natural landscape. That will hurt them, but first there’s a castle to storm. It falls easily, and Macbeth is killed, ending his eighteen year long reign. The English commander, Siward (Darrell D’Silva), receives the news of his son’s death, and in the first major departure from the story we know, is deeply upset. In the second major departure, Queen Gruach (Siobhan Redmond), better known as Lady Macbeth, is taken alive. Malcolm (Ewan Donald) demands her immediate execution, but Siward decides enough blood has been shed today. He came to this country to establish peace for all its people, even her.

Indeed, Siward is determined that Scotland become a just, peaceful, democratic country. Malcolm is quite irritated by this obvious failure to understand the clan-based society Siward has blundered into, and prefers a more Machiavellian approach. Macduff (Keith Fleming) explains, because Malcolm does not, that Macbeth actually enjoyed support from many chieftains, and that Gruach can argue her son from her first marriage, Lulach (Kyle Curry), has a more legitimate claim to the throne than the Dunkelds. Currently the boy is in hiding, while insurgent forces remain loyal to him and his mother. Siward hopes to reconcile Gruach and Malcolm some way, but finds her wily and seductive. Meanwhile, his soldiers are surprised and angered to face continuing resistance, and many are not sold on the whole idea of being there to help the Scottish people, while the chieftains on both sides of the civil war are scornful of English notions of civilization. As the occupation draws on without political settlement, the war only gets worse.

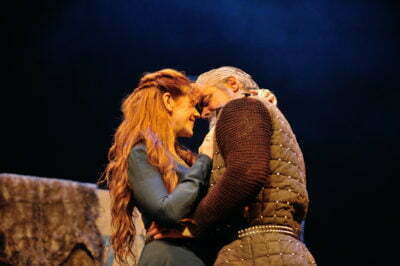

The depth of character displayed by the entire ensemble gives the story its epic scale. But the leads, Redmond and D’Silva, embody the spirits of their characters’ opposing cultures. Gruach is as cunning and beguiling as ever, but a very different person than Shakespeare’s version. She would absolutely never dash Lulach’s brains out in pursuit of her own power; he’s her king now, and she is completely devoted to what is best for him. However, should something happen to him, any boy can be Lulach. Redmond plays Gruach as absolutely certain and with a clarity of perception that is ambiguously mystical. Her manner of speaking makes clear English is not Gruach’s first language, yet her mastery of it demonstrates keen intelligence. She refuses to be intimidated, and yet, she senses something compassionate in Siward. Something to manipulate, but also to appreciate.

While Gruach dominates the first act, the second is more focused on Siward’s fall into madness. D’Silva starts Siward off as a man firmly dedicated to the principles he claims, although hubristically unprepared. The death of every one of his soldiers hits him as hard as the loss of his own son, and it is fury at their loss to Scots who are the complete opposite of everything he cherishes that drives him over the edge into tyranny. D’Silva has an earnestness about him that makes it easy for the other actors to play admiring him. But I think the main weakness in Greig’s script is that when Siward loses his cool following a humiliation at Gruach’s hands, his army goes on a rampage for years, and everybody still refers to his fundamental goodness. In the middle of act ii, he does something so horrible I cannot understand why Gruach, of all people, still sees anything in him.

Director Roxana Silbert manages the rest of the cast and the design elements to support the story so that nearly everything is clearly interrelated. Alex Mann plays Egham, a cynical English officer who by working within the Scots’ brutal system, manages to get along better with them. Donald’s Malcolm is a sneering, venal voice of reason. A small band plays music composed by Nick Powell that makes the modern parallels even more explicit and gives this version of Scotland its distinctive culture, along with Helen Darbyshire and Mairi Morrison’s singing in the roles of Gruach’s attendants. There’s not much to Robert Innes Hopkins’s set, except a large Celtic cross. Christianity isn’t really emphasized as a part of either nation’s culture, but differences between the Celts and Anglo-Saxons are foregrounded.

It is important to note the English atrocities against the Scots are mostly reported to us by the English soldiers themselves, and rarely depicted explicitly. There are a few scenes, however, of the soldiers kicking around the smaller members of the cast (who are mostly the local Chicago actors) that provide enough taste of war’s general ugliness. Greig, who supports Scottish independence, may now regret having compared his own country so explicitly to Afghanistan and argued in his play that the English leaving would mainly benefit the English. My teachers have generally taught Macbeth as an example of Stuart propaganda and I think the disastrous consequences of our recent wars are generally understood, but Dunsinane still expresses an interesting perspective in focusing on how events are shaped by irrational personality quirks of those involved, rather than on mainly economic factors like other post-colonial plays might. In that way, I think it’s a worthy sequel to Macbeth, and a fine, moving story.

Highly Recommended

Jacob Davis

[email protected]

Reviewed March 4, 2015

For more information, see Dunsinane’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing at Chicago Shakespeare Theater, 800 E Grand Ave, Chicago. Tickets are $58-78 with discounts for groups of 10 or more. To order, call 312-595-5600 or visit www.chicagoshakes.com. Plays through March 22, Tuesdays-Fridays at 7:30 pm, Wednesdays at 1:00 pm, Saturdays at 3:00 pm and 8:00 pm, and Sundays at 2:00 pm. Running time is about two hours and thirty-five minutes with one intermission.