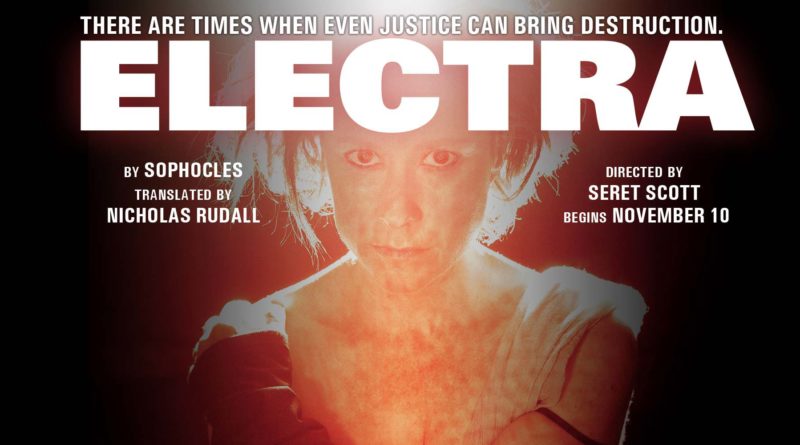

Electra

By Sophocles.

Translated by Nicholas Rudall.

Directed by Seret Scott.

Produced by Court Theatre, Chicago.

By Frenzied Lust this Production was Made!

Completing their three-year cycle of plays about the fall of the House of Atreus translated by Nicholas Rudall, Founding Artistic Director of Court Theatre and Professor Emeritus in Classics at the University of Chicago, Court Theatre premiered this week Sophocles’ Electra. Patrons who saw the first two of this cycle (Euripides’ Iphigenia at Aulis and Aeschylus’ Agamemnon) will perhaps feel compelled by a need for finality or a sense of obligation (or perhaps your season ticket burning in their wallets) to see this last one—very well. I speak then to the rest: let not your earnest appreciation of “Classics” or your instinctive fascination with the past lead you (as it led me) to behold the profane confusion that besets this production.

Far from demonstrating to us the modern resonance of Electra’s agony for Justice, or—what would be more beautiful—preserving for us the Greek tragedy in its authentic voice and style, Court Theatre’s production demonstrates only what I interpret to be the schizophrenic attempts of a group of artists to render distracting that which for them they find no meaning in or connection to—there is (to the chagrin of many, I’m sure) no contemporary, luridly social or political angle to mine here—but which they find incumbent upon themselves to produce nevertheless. The result is a chimeric monstrosity of magniloquent lyricism blended with naturalistic, contemporary parlance; a cappella singing punctuated by agonized wailing; Greek foliage planted amidst anachronistic Plantation style shutters; a medley of costume styles totaling a world-less effect; languid movements suggestive of piety (and sign language?) coupled with—Spanish phrasings? “Why?” ask you? Why not!

To bring us all up to Electra: prior to Electra, Agamemnon, to appease the goddess Artemis in order to allow his troops to reach Troy, sacrificed his daughter, Iphigenia (Iphigenia at Aulis); then, to avenge the death of her daughter (and because she had, during Agamemnon’s 10-year absence, taken up an adulterous affair with Aegisthus, Agamemnon’s cousin and rival to the House of Atreus), Clytemnestra murders Agamemnon, prompting Electra to send her brother, Orestes, into hiding (lest her mother should murder him, too), until the time when he might return to avenge his father’s death (Agamemnon).

Electra begins a few years later, back in . . . Argos? Floor-to-ceiling Plantation style shutters make up the exterior of the palace, each double-panel of the 20-foot shutters consisting of a door lever (making them doors, apparently), the façade complete with a balcony. All this stares down on what must be a public space, with tufts of Greek foliage planted on wooden boards. So . . . a non-traditional setting?

Enter the man of the hour, Orestes (Thomas J. Cox), along with his best friend, Pylades (Rashaad Hall), and his tutor and guardian, Paedagogus (Dexter Zollicoffer)—all of them (inexplicably) appearing as though they’ve just stepped off the set of a 2016 remake of Lawrence of Arabia. Orestes, now 20 (but looking much more like 40) and wearing an absurd wig of braided hair, has finally come to exact revenge against his mother, Clytemnestra (Sandra Marquez). And see how the young man shakes with confidence in his knees! He will surely do it! (Uncontrollable bouts of shaking are sure to come to some actors—but woe unto them for whom they come!) Rather than dispatch the revenge straightaway, the three men devise a plan in which Paedagogus will first declare to Clytemnestra the death of her son, and then the other two, after honoring Agamemnon’s grave, will come to murder her.

Electra (Kate Fry), who for these past three years has done naught but mourn her father and hope for Orestes’ return, is inconsolable in her grief and undeterred in her hope for just vengeance upon her mother and stepfather, Aegisthus (Michael Pogue)—who themselves have done naught but oppress her, keeping her locked up. Indeed, though she appears mad in her attire—an attire that is indeed mad, consisting of her father’s duster jacket over a black, tattered dress—Electra answers the sympathetic but palliative words of the chorus of Mycenae women (Caren Blackmore, Cruz Gonzalez-Cadel, and Tracy Walsh)—themselves adorned in bright blue dresses!—with reasoned and firm responses.

Once she learns of Orestes’ death, however, Electra vows to exact vengeance herself—never mind the cowardly cautions of her sister Chrysothemis (Emjoy Gavino)! The well-dressed nuisance! Fortunately, before her grief follows through in rash action, Orestes presents himself to her and they are happily united—for vengeance!

Here, typically, is where I would endeavor to elucidate what this production is, who it is designed for, and what its intentions were, so as to juxtapose those answers with my “critical review.” However, I cannot fathom the answers to these questions, and so I offer—this production is an abortion, it was designed for fun, and its intentions were to make a show of a new translation. Besides that, let more erudite minds attempt to corral the disparate elements of this burlesque into a cohesive whole.

But—no! This judgment is too rash. This, after all, is an Equity company, so surely there is method to Electra’s madness. Let me look into these elements, seriously now, and attempt to be erudite myself.

To begin easy: What is the design of this production? As I’ve mentioned (three times now!), the set consists largely of Plantation style shutters. Very well, we are in 19th century America (or else in the 1980s, when this style had resurgent popularity). But the foliage is unmistakably Greek. Never mind—forget the foliage—burn the foliage—the foliage is no importance! But the men are dressed in zippered, adventure attire, with accessorized belts, modern scarves, buckled boots, cross-chest satchels—like out of some action game (N.B. zippers were invented in 1913); and the women are dressed formally, in turquois or pale blue dresses; and Aegisthus is dressed—unlike any of them!—in a black suede lounge jacket (complete with matching vest) and military-striped pants—as though he just finished a set of Marvin Gaye for our soldiers at an AFE-sponsored event.

Attempting to rationalize this all, I am flummoxed. What world is this? Greece? America? Middle Earth? The production booklet contains a section entitled “Designer’s Notebook,” in which it reads that costume designer Jacqueline Firkins “infuses her costumes with symbolic meaning, designing pieces that reveal fundamental truths about each character’s intentions, emotions and state of mind” (emphasis mine). This gives no answer, only philosophy musings that never touched ground on the stage. Nevertheless, one is certain to have a good chuckle reading about all the fundamental truths sewn into the stitching. If only these truths had an intelligible world in which to exist.

But what of the acting? If all the performances had been in the same production, then much could be excused: then, there would at least be a grounding for understanding the outlying elements. But, alas!, not even this was to be! Seret Scott articulates no clear, unified vision for this production and lets her actors stray in style, just as she lets her production team run wild with their imaginations.

From beat to beat, one is just as likely to experience the elevated style of “Greek tragedy” as to experience the naturalistic, everyday delivery of a contemporary domestic drama. And, what’s more confounding, Mr. Rudall’s translation seems to support this, as his dialogue moves cumbersomely from the poetic elevation of choral meditations and laments (e.g. on Justice, the gods) to the more casual exchanges, such as, “You’ve got white hairs in your beard” (approximate rendition). And so the actors interpret these beats as jumping 2500 centuries and deliver them in today’s parlance.

To transition from a poetic, choral interlude—what with the Chorus’ vague, choreographed gestures—to an exchange in which an actor or actress throws his or her line for comedic effect is both bizarre and offensive. How is one to take this tragedy seriously when there’s this foreboding drone one moment (a nice touch by Andre Pluess)—the the chorus intoning (beautifully, I might add) and beating their breasts, Electra is writhing upon the ground—and then the next moment, say, Chrysothemis appears and Gavino plays her with all the petulance of a child out of a middling domestic comedy?

But the audience did laugh! Oh-ho! All the lines about mother being an indomitable pain in the tochus, they sympathized with that! Even as Clytemnestra is being murdered—Electra yells out, “Strike her again!” and Clytemnestra shouts, “I am struck again!”—they laughed and laughed.

But the cast should not be encouraged by their audience’s laughter for this production. It is not the laughter of an audience who is proud to have picked up on a well-timed joke. (There is not much to laugh about, in fact, regarding matricide. Just read the papers.) Rather, it is the laughter of a people who are so outside the world of the production that, grasping slack-jawed for its intelligibility, they find alien the turmoil paraded before them and, so detached, are amused to find their drifting thoughts of dinner reservations and impending divorce proceedings interrupted by a phrase that recalls their favorite television sitcom. Indeed, so far from resonance is this production with its audience that they isn’t even a sympathetic vibration—excepting, of course, in untouched overtones of comedy. And who could blame them? Not me, who felt just as nothing—but did not laugh, at all.

Granting all that’s been said, regardless of acting style only a few lines find true, honest emotion in the cast. Kate Fry, as Electra, who bears the weight of this production, finds obvious beats to break up the long blocks of dialogue, but still fails to have me believe—in my gut—that she is as distraught and conflicted as her mourning and flailing indicates. Thomas J. Cox, as Orestes, is simply miscast. I saw more substantial depth and anger in Rashaad Hall’s mute eyes as Pylades than I did in his. Even when he emerges from murdering his mother, his hands all bloodied to see, I still didn’t believe he had it in him (the other two must have struck her, I think).

Sandra Marquez’s performance, as Clytemnestra, is easily the best in this production: she has the gravitas of a matriarch who would just as soon clutch you to her breast as cut you nape to navel. Nevertheless, there was more complexity to be found in her character, too. Cruz Gonzalez-Cadel deserves recognition, as well, for she communicated the most earnest feeling in her Chorus role, at some points even shedding tears (though, why they have her sometimes speaking in Spanish I still do not understand).

One year ago, a newly established theatre company called Salt Box Theatre put on a humble production of Euripides’ The Bachae. In a black box no bigger than a walk-in closet, equipped only with masks, red fabric, a plaster head, and their lithe and willing bodies, their production (if but for a brief month!) revived Greek tragedy in Chicago. The resonance is still there; we are still heirs to Greek lineage; their tragedy is human, our own. Court Theatre’s “missing of the mark” in their Equity production of Electra is indeed worthy of the name—“tragedy.”

Not Recommended.

August Lysy.

Reviewed on 19 November 2016.

Playing at Court Theatre, 5535 S. Ellis Ave., Chicago. Tickets are $48-$68. For tickets and information, call the Court Theatre box office at 773-753-4472, or visit CourtTheatre.org. Performances are Wednesdays and Thursdays at 7:30 p.m., Fridays at 8:00 p.m., Saturdays at 3:00 p.m. and 8:00 p.m., and Sundays at 2:30 p.m. and 7:30 p.m. through December 11th. (Exception: no show on Thursday, November 24th). Running time is 90 minutes with no intermission.