Eurydice

By Sarah Ruhl

Directed by Julie Ritchey

Produced by Filament Theatre Ensemble

At the Lacuna Artist Lofts, Chicago

Please don’t get me wrong, see, I’ll forgive you in a song

It is entirely unimportant, when adapting tales from Ovid, to remember that he was an insolent little prick and a satirist (at one point in his Pyramus and Thisbe, Pyramus stabs himself in the groin – not the gut or the heart – and Ovid likens the result to “water bursting from a rusty pipe”) who was so flamboyant and iconoclastic that Augustus exiled him from Rome, and he spent the remainder of his life writing insipid poems pleading to Augustus to allow him back into The City. It is unimportant to remember this because, if one so chooses, one may simply take the tragic nut of the story, and retell it as one likes, losing the snarky asides and sarcasm in the original. And this is what Sarah Ruhl has done with her retelling of the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice.

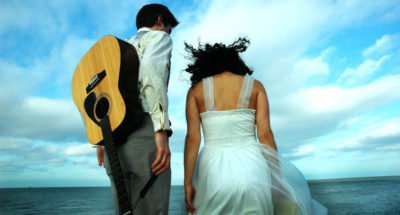

Her adaptation could not be called simply a “modernization” of the story: yes, people wear contemporary clothes, and speak in contemporary ways, but it’s not Jean Anouilh’s Antigone to Sophocles’ original. For one thing, Ruhl tells the story from Eurydice’s point of view, instead of Orpheus’. However, more than that, she reimagines the entire myth. Orpheus and Eurydice are not the perfect couple: they have their squabbles and their problems; Orpheus is so immersed in his work, in his music, that he sometimes forgets to speak, sometimes neglects, all-too-innocently, his darling dear. He is not particularly manly: his shoulders aren’t broad enough; he is not very strong. Eurydice, for her part, is also variously inept – she has no sense of rhythm, for one thing. Instead of dying by a viper, she falls down a set of stairs, and, upon reaching the Underworld, is greeted by three stones and her father, all inventions of Ruhl, who also changes the ending, though keeping it tragic (and perhaps even enhances its tragedy).

Her adaptation could not be called simply a “modernization” of the story: yes, people wear contemporary clothes, and speak in contemporary ways, but it’s not Jean Anouilh’s Antigone to Sophocles’ original. For one thing, Ruhl tells the story from Eurydice’s point of view, instead of Orpheus’. However, more than that, she reimagines the entire myth. Orpheus and Eurydice are not the perfect couple: they have their squabbles and their problems; Orpheus is so immersed in his work, in his music, that he sometimes forgets to speak, sometimes neglects, all-too-innocently, his darling dear. He is not particularly manly: his shoulders aren’t broad enough; he is not very strong. Eurydice, for her part, is also variously inept – she has no sense of rhythm, for one thing. Instead of dying by a viper, she falls down a set of stairs, and, upon reaching the Underworld, is greeted by three stones and her father, all inventions of Ruhl, who also changes the ending, though keeping it tragic (and perhaps even enhances its tragedy).

It is a strong play that hovers between magical realism and surrealism. The language in the piece is cared for, nurtured; Ruhl clearly loves words, loves the sound of them, loves playing with them and retooling their meanings. She loves words as a poet loves them.

And director Julie Ritchey loves the play as a director loves a play. She has burrowed deep and nestled in its earthy, root-filled warmth. She has eaten this play, drunk this play, dreamt and woken this play. And not without advantages. The moments she creates – crafts, more like – are heartfelt and complex. The set simple, yet supple, ample, yet full; the lighting and sound well-designed; the costumes almost all treasure troves from vintage boutiques; and the original music by Peter Oyloe and Shannon Bengford soaring, surprising, tantalizing. Ritchey has assembled an admirable artistic vision, and executed it. Though not without help: every actor on stage was nearly pitch-perfect. Carolyn Faye Kramer, Peter Oyloe, and Patrick Blashill (Eurydice, Orpheus, and Her Father, respectively) all deserve particular mention: Kramer’s Eurydice was subtle and smart, soft but strong, with an altogether – pardon me, but I must say it – feminine strength. To use mysticism as a metaphor quickly, she has the Yin that brings Yang to its knees. Oyloe plays Orpheus as the hopeless musician and wistful romantic who only realizes his faults once it’s too late. And Blashill’s Father is touching without falling into sentiment, melancholy without drooping into melodrama. The rest of the ensemble is also quite up to snuff.

And director Julie Ritchey loves the play as a director loves a play. She has burrowed deep and nestled in its earthy, root-filled warmth. She has eaten this play, drunk this play, dreamt and woken this play. And not without advantages. The moments she creates – crafts, more like – are heartfelt and complex. The set simple, yet supple, ample, yet full; the lighting and sound well-designed; the costumes almost all treasure troves from vintage boutiques; and the original music by Peter Oyloe and Shannon Bengford soaring, surprising, tantalizing. Ritchey has assembled an admirable artistic vision, and executed it. Though not without help: every actor on stage was nearly pitch-perfect. Carolyn Faye Kramer, Peter Oyloe, and Patrick Blashill (Eurydice, Orpheus, and Her Father, respectively) all deserve particular mention: Kramer’s Eurydice was subtle and smart, soft but strong, with an altogether – pardon me, but I must say it – feminine strength. To use mysticism as a metaphor quickly, she has the Yin that brings Yang to its knees. Oyloe plays Orpheus as the hopeless musician and wistful romantic who only realizes his faults once it’s too late. And Blashill’s Father is touching without falling into sentiment, melancholy without drooping into melodrama. The rest of the ensemble is also quite up to snuff.

There were minor issues that I would be remiss not to recount – though the technical issues were so small, and so clearly one-night wrinkles that were ironed out even before the troupe left the theatre, that I am almost loathe to mention them: there was one instance when a line was drowned out because of the sound, and a single light fixture was somehow bumped and was shining low on one side of the audience. As I said, these are minor, one-night issues that I only mention because I feel I somehow have an obligation to. And if these quibbles hold this play back at all, it would be scandal. The other caveat I had may simply come from my lack of experience with the show (I fully acknowledge never having read the play): there are three stones in the Underworld, the Small Stone, the Large Stone, and the Loud Stone; but it seemed to be that, generally, all three of them were rather loud – at least at times.

There were minor issues that I would be remiss not to recount – though the technical issues were so small, and so clearly one-night wrinkles that were ironed out even before the troupe left the theatre, that I am almost loathe to mention them: there was one instance when a line was drowned out because of the sound, and a single light fixture was somehow bumped and was shining low on one side of the audience. As I said, these are minor, one-night issues that I only mention because I feel I somehow have an obligation to. And if these quibbles hold this play back at all, it would be scandal. The other caveat I had may simply come from my lack of experience with the show (I fully acknowledge never having read the play): there are three stones in the Underworld, the Small Stone, the Large Stone, and the Loud Stone; but it seemed to be that, generally, all three of them were rather loud – at least at times.

This hardly got in the way of enjoying the play as it unfolded, however. Filament’s production of Eurydice is stimulating, engaging theatre, well-conceived and well-executed. It challenges: it wants us to work, wants us to think, want us to take something away after 90 minutes, instead of leaving us with empty entertainment. It asks us to participate, to grow and change with the piece. And, I think, it succeeds.

Highly recommended

Will Fink

Reviewed on 4.22.11

For full show information, visit TheatreinChicago.

For its companion piece, Orpheus, visit here for our review, and here for TheatreinChicago.

At the Lacuna Artist Lofts, 2150 South Canalport, Chicago, IL; for tickets, visit www.filamenttheatre.org; $10-35; performances Friday-Sunday at 7:30 pm, running time is 85 minutes without intermission, through May 29th.

Julie,

Holy Toledo! What a marvelous review of what sounds like a fascinating play (with some delicious adaptations) — by everyone involved, and, of course, particularly by the director — (this evaluation coming from a slightly biased Tonganoxie dental patient)!

I hope the next stop for the play will be the KC area!

Sidney Roedel