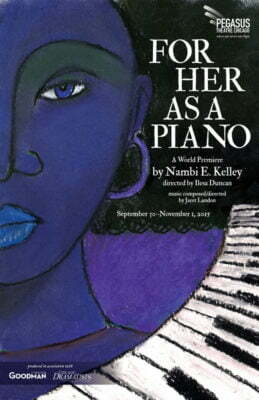

For Her As A Piano

Directed by Ilesa Duncan

Music Composition & Direction by Jaret Landon

Produced by Pegasus Theatre Chicago

Playing At Chicago Dramatists, Chicago

A Mystical Reconciliation With the Ever-Present Past

Pegasus Theatre Chicago launched its 2015/2016 season last week with the world premiere of For Her As A Piano. A new play by the critically acclaimed adapter of Native Son, Nambi E. Kelly, For Her As A Piano is a mystical tale of one woman’s reconciliation with her family legacy, detailing the troubled lives of three generations of women across time and space using vignettes and choral accompaniment. While the choral singing in the production is beautiful and captures the mystical aesthetic of the play, I found the nature of the storytelling did not lend itself to strong sympathies with the characters, rendering the play an interesting concept but with little emotional engagement.

For Her As A Piano opens with the chorus vocalizing harmonically in the dark. Then the lights come up and we see Sarah (Toya Turner) lying upon a black stretch of the set, designed (by Lauren Nigri) as a surreal-looking piano. A woman in a doctor’s gown enters, creating the space of a doctor’s office, and wakes Sarah from a nightmare to inform her that she will need to have surgery on her uterine fibroids. What alarms the 39-year-old Sarah about this diagnosis is not the surgery itself – not even the bizarre behavior of the doctor – but the fear that this may mean the removal of her uterus and the end to her hope of becoming a mother.

From this brief scene, the play transitions to what might be construed as another dimension, free from contextual constraints of time and space and narrated by Piano (Camille Robinson) with help from her chorus. It is quickly established that Sarah harbors some grievance against her family legacy (which she confesses she knows little to nothing about); so Piano then proceeds to show her the truth of her legacy by showing her scenes from the lives of her mother, Mary (Nadirah Bost), grandmother, Delores (Toni Lyncie Fountain), and even her own. The truth is shocking and humbling to Sarah, who, by the end, discovers a newfound sympathy and appreciation for her family and learns, as Piano told her from the beginning, that they are all connected through time and space.

Although its mystical storytelling, tonal singing, and rhythmic dialogue and lyrics (at times reminiscent of beat poetry) are in its own, distinct voice, For Her As a Piano invites comparison to the storytelling of A Christmas Carol. In both, the protagonists are taken through time and space to confront the hidden truth of their past, witnessing the unfavorable circumstances of those around them and thereby learning sympathy and gaining awareness of their own, shortsighted callousness.

The comparison is apropos because I believe it illustrates why For Her As A Piano fails to incite much sympathetic attachment to the protagonist and why A Christmas Carol succeeds. The difference between the two lies in “choice.” In A Christmas Carol, the metaphysical experience essentially redounds upon Scrooge’s immediate choices of what to do in the present: the past and present are shown to exhibit his current, ill-humored character, and the future is shown to foretell how he will be remembered if he continues in this character.

In For Her As A Piano, Sarah does not confront a pivotal choice in the present. Hers and her family’s past (and, to be clear, it is only the “past” that we see, mysticism notwithstanding) is intended to change her state of mind regarding her legacy and her place in it. While there is a scene that shows forgiveness, it is not a resolution to a conflict as is traditionally construed on the stage. Though we do see the heinous and scarring troubles of each of the women’s lives, they are not presented as conflicts that inhibit explicit aims but as the unfortunate happenings of life: rape, mental illness, abuse. The affect of all this on the audience would be akin to Scrooge only visiting the past in order to witness the pathetic reality of Tiny Tim: the audience would feel sorry for him – but what of it? What more could we say except that’s just terrible, but for the grace of God go we all.

This absence of established sympathy with Sarah (and the other women) is the principal weakness to what could have been a compelling and grand epic of human life. But what also makes this play difficult to understand, on a more intellectual level, is the specific grievance Sarah holds against her legacy, particularly since she confesses to not knowing the truth about it at all. This, however, may have been a fault on my part for missing key information early on, or it may have been due to some difficulty hearing what the actresses were singing at certain parts in the story, which itself may have been the result of poor diction or poor acoustics.

What For Her As A Piano does well is choral singing. With literally no musical accompaniment, the chorus of all-female singers vocalize and sing in beautiful, deep harmonies that seem to evoke the richness, wonder and mystic aesthetic of their timeless and space-less story of legacy.

Additionally, the actresses’ performances show an impressive range, as many of them take on various roles or depict their characters at different ages. Nadirah Bost, for example, plays Mary, at times a schizophrenic, temperamental mother with a bitter scowl, at other times a motherless child with doleful eyes. Toni Lyncie Fountain as Delores also gracefully manages the abrupt transitions between her characters, from a selfish, hateful mother, to a helpless, abused child – to even a scooter-riding, talking bear! And the cross-gender acting by DuShon Monique Brown (a radical activist) and Nicole Michelle Haskins (a roving-eyed teen turn middle-aged, podiatrist hunk) is remarkably believable, as well.

Though the choral singing, poetic dialogue, and acting often shine beautifully, I don’t think they compensate for the story, which, from the beginning, already foretells its conclusion in its clever yet ultimately formulaic and repetitious unfolding. Nevertheless, Kelley’s storytelling is unpretentious and honest in its singular aim, which, from what I’ve seen, makes it stand out from other, contemporary shows.

Recommended

August Lysy

Playing at the Chicago Dramatists, 1105 W. Chicago Ave., Chicago. Performances are Thursdays – Saturdays at 7:30 p.m. and Sundays at 3 p.m through November 1st. Running time is 120 minutes with one, ten-minute intermission.