God of Carnage

Translated by Christopher Hampton

Directed by Rick Snyder

At the Goodman Theatre, Chicago

The Banality of Bourgeois Evil

God of Carnage is not about the destination: when the four actors come on stage, you already know that, in the end, they will tear each other apart. What God of Carnage is about, ultimately, is what statements the playwright makes in the 75 minutes she has our attention. And what she says is not in the strictest sense novel: in a world where gods acted like oversized, all-powerful humans (that is, not unlike the people in the Stanford Prison Experiment), neither Plato nor Paul could claim to be visionaries when they stated that people were on occasion desperately terrible to one another. Nor is it novel to laugh at human suffering: I need only mention Seinfeld. But that does not make Yazmina Reza’s play superfluous – on the contrary, reminding us all of the facade in which we live and call “civilization” is of greatest necessity.

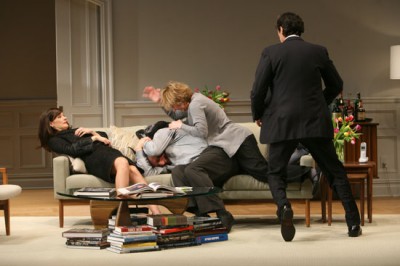

Two pairs of parents, both bourgeois, meet because one parents’ boy has hit the other parents’ boy in the face with a stick, and the victim’s parents wish to discuss the occurrence in a polite, civilized manner. As the discussion proceeds, social barriers break down and the parents become, ultimately, far crueler than their children: Adults, after all, have a far greater capacity for cruelty, as they are much more intellectual and imaginative in its implementation. One couple consists of a high-powered lawyer working for a pharmaceutical company whose wife is in “wealth management,” and the other of a wholesaler and a writer, who is currently working on a book about the crisis in Darfur. As one might expect, the woman writing about Darfur is the most insistent about civility: she is the Conscientious Liberal, and seeks to right the wrongs of the world. Her husband plays along as best he can, but since he was once of a different class – he is the only person on stage who, so to speak, works for a living – he sometimes has trouble. The lawyer is married more to his phone than to his (second) wife, and does his job very well: he protects his clients as best he can, even when they have done something wrong; he is a typical alpha male. He also has experience in Africa, and discusses its situation with the writer: they teach kids to kill by age 8, he points out, and call grenade launchers “thump guns.” His wife is more or less a housewife, whose main charge is taking care of their children – especially since he finds himself quite useless in the task.

They are, on the whole, four normal people. They could be anyone in the audience. Which is the point: God of Carnage is Yazmina Reza’s indictment of the audience, indeed of the West. All the primeval urges in Africa – the rape, the killing, the dehumanization – are still ever-present in Western civilization: they’re just not naked here. Here, we cloak our brutality and maintain the fiction that we are beyond such raw, primordial acts. Reza’s point is that Hobbes, though perhaps over the top, was onto something with his State of Nature; and that Hannah Arendt was righteously armed with the truth when she penned The Banality of Evil. Indeed, Arendt’s hypothesis is pervasive in this piece: how can four normal, Western people strip each other bare, and claw each other raw? The four individuals on stage are not meant to simply be the four people on stage; they are Everymen and Everywomen – there are parts of each of them in all of us. Although we disagree, and vehemently, with some of their thoughts and actions, we see our own opinions up there as well, given voice.

This play is vital and powerful. I believed that when I saw it three years ago at the Bayerisches Staatsschauspiel in Munich and I believe that today.

And yet I found the Goodman’s production, while good, still wanting. It started off very strong; the four actors and director had complete control. However, as the piece went on, it lacked the restraint that the play needs to be really exceptional. The heart-wrenching moments are far less heart-wrenching when they are blatantly, bombastically on the surface. They should need to be dug out, a bit – their excision should be painful. And although Rick Snyder was adept at directing the audience’s attention to where he wanted it to go (all the subtleties of body language, slight movements, a wry glance were caught), he missed the subtleties of the emotions: The neuroses and nervousness that led to one character’s eventual vomiting were not stressed enough, so the hurling seemed instead to come out of nowhere. Which is not to say that the actors were anything less than good: indeed, David Pasquesi (Alan) played his role perfectly. Beth Lacke (Annette) was marvelous for the first half of the play, but, like Mary Beth Fisher (Veronica) and Keith Kupferer (Michael), seemed to lose control as the play went on. Indeed, the shouting match that the play necessarily devolves into was overwrought, volume substituting for intensity. Because of the height of the emotions, Annette’s impulses regarding her husband’s cell phone and the tulips lacked the shock and Pinter-esque, uneasy horror that should be evoked. Indeed, the audience cheered when she cut her husband off from his job. Keith Kupferer’s Michael was presented as an archetypal “American working-class” man, and that side was played up (loud, Brooklyn drawl; gruff and insensitive); but his insecurities (the feeling that he may not belong in his neighborhood, with high-powered lawyers for neighbors) were glossed over.

Which may be the problem: maybe this play just doesn’t work in an American setting. Maybe the four people on stage acted like typical Americans would act – but that doesn’t further the piece; in fact, it detracts from it. The typicality of these four Americans – loudmouths who get their way with volume and overwhelming force instead of sharp-tongued argument – makes this God of Carnage more of an oddity, and a farce, than it was ever meant to be. Yazmina Reza once said, “I would like to see [audiences] laugh at the right moments.” In this production, because of the decisions made by director and cast, they do not. Which is not to say that this is a bad play, or that this production is not entertaining – on the contrary. It is simply not all that God of Carnage could be.

Recommended.

Will Fink

Reviewed on 3.13.11

For full show information, check out the God of Carnage page at Theatre In Chicago.

At the Goodman Theatre, 170 N. Dearborn, Chicago, IL; call 312-443-3800 or visit www.goodmantheatre.org; performances Wednesday and Thursday at 7:30, Friday and Saturday at 8 p.m., and Thursday, Saturday and Sunday at 2 p.m.; running time 75 minutes, without intermission; through April 17th.

Snyder is Directing a film also. In Italy. Written by former theatre critic Lucia Mauro.