The Gospel of Franklin

Directed by Robert O’Hara

Presented at Steppenwolf’s First Look Repertory of New Work

Playing at Steppenwolf Garage

This beautiful new play about sin, forgiveness and looking back is a must see…

Playwright and Steppenwolf Literary Manager Aaron Carter is featuring his new play The Gospel According to Franklin—with direction from Robert O’Hara—as part of Steppenwolf’s First Look Repertory of New Work. Featured alongside new plays by fellow First Look writers Janine Nabers and Edith Freni at the Garage, The Gospel of Franklin stands out as an especially poignant and well-crafted memory play with dynamite performances from its all-male cast.

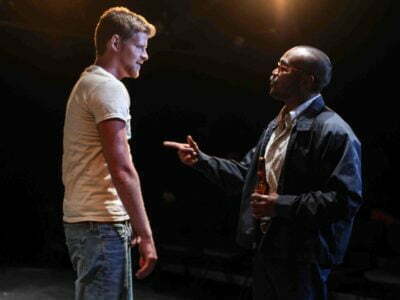

At the center of the play is Franklin (performed by Gavin Lawrence in a knock-down, riveting performance), a black assembly-line worker in Ohio, often found proselytizing to scruffy white boys hard on their luck. Among his frequent devotees are the crypto-homo speed freak, Ben (Rob Fenton); the elusive Jesse (Tim Frank), whose best friend recently shot himself in the head; and Ralph (Keith D. Gallagher), a former coworker who lands himself in prison for the death of his own son. Part life coach, part father figure and part evangelizing minister, Franklin is apparently willing to don any number of hats while offering the redeeming salvation of Jesus Christ to the down-and-out.

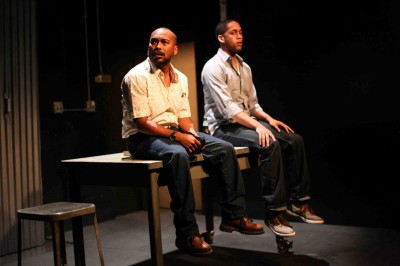

But Franklin’s mission has a darker side. Or at least one not so entirely straightforward. Especially as told by Franklin’s son William (played by Julian Parker with a disarmingly neurotic charm), whose narrations act as something of a prism, refracting his father’s life story to us as slightly skewed and at an angle. Unsure of how he is to feel about Franklin, William is equally unsure of how to tell his father’s story. So his version is full of suppositions and openly hypothetical happenings, forcibly drawing connections from A to B when in reality the connections are anything but linear.

But Franklin’s mission has a darker side. Or at least one not so entirely straightforward. Especially as told by Franklin’s son William (played by Julian Parker with a disarmingly neurotic charm), whose narrations act as something of a prism, refracting his father’s life story to us as slightly skewed and at an angle. Unsure of how he is to feel about Franklin, William is equally unsure of how to tell his father’s story. So his version is full of suppositions and openly hypothetical happenings, forcibly drawing connections from A to B when in reality the connections are anything but linear.

All William knows is that his father was far more patient and forgiving with these strange men than he ever was with him growing up. To William, Franklin was a harsh taskmaster, often in revealingly excessive ways. Sure, there were plenty of pedestrian arguments over things like the trashy sci-fi novels William might bring home. But Franklin, oddly aware of how a wayward sexuality can pull a person off course, also subtly admonishes his son against sleeping with his own mother. In one particularly unnerving scene (all the more so for its studied plausibility), Franklin cautions William against hugging his mother too tightly—lest she get the wrong idea. Instead, he says, William might try hugging her from the side, his arm draped inoffensively across her shoulder.

But Franklin is nothing if not a man of contradictions, and Franklin’s zealousness for the destitute may have something to do with his repressed homosexual longings for them. Or at least one can’t rule it out. As William says, from the outside looking in, Franklin’s involvement with these men looked and sounded like a sexual relationship. There was always the initial flush and excitement of meeting, the cumulating frenzy of getting to know one another, then the inevitable let down followed by unanswered phone calls and missed lunch dates. Plus there were the drunken father-son outings to Chicago gay bars. As Franklin tells his son (while sipping on a ‘Sex On the Beach’ in Boystown), he likes to be around gay men because they tell it like it is; they don’t lie or equivocate or avoid the truth. One can see their appeal to Franklin.

But were it that easy. As The Gospel of Franklin makes clear, the truth isn’t always so easy to say. Buried underneath years of repressed memories, falsehoods and dissembling appearances, the truth—even of those we love and know best—becomes fractured, woolly and hard to sort through. Aaron Carter’s play is hence not unlike a jigsaw puzzle whose pieces don’t quite fit together but which nonetheless form some exhilaratingly incongruous biographical snapshot.

falsehoods and dissembling appearances, the truth—even of those we love and know best—becomes fractured, woolly and hard to sort through. Aaron Carter’s play is hence not unlike a jigsaw puzzle whose pieces don’t quite fit together but which nonetheless form some exhilaratingly incongruous biographical snapshot.

Thankfully The Gospel of Franklin doesn’t require any clear and distinct view of Franklin’s contradictory character. For the real message of The Gospel of Franklin is ‘forgiveness.’ Forgiveness at the risk of never really seeing the people we love. Forgiveness, because the blind can’t throw stones.

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

Reviewed by Anthony Mangini

Reviewed Wednesday, August 14th, 2013.

Running time is approximately 90 minutes with no intermission.

The Gospel of Franklin runs until August 25th, 2013. Steppenwolf Garage is located at 1624 N. Halstead St. For more information and reviews, check out its Theater in Chicago listing at https://www.theatreinchicago.com/the-gospel-of-franklin/6352/.