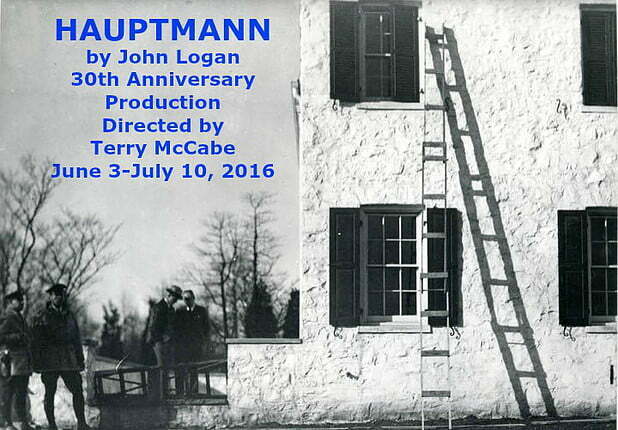

Hauptmann

By John Logan

Directed by Terry McCabe

Produced by City Lit Theater, Chicago

Hauptmann’s Case Still Fascinating

Before he wrote the Tony Award-winning Red and the screenplays of The Aviator, The Last Samurai, and Gladiator, John Logan was fascinated by courtroom dramas. His early play Never the Sinner, about Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, played in Victory Gardens last year, and now, City Lit Theater is reviving Hauptmann for that play’s thirtieth anniversary. Artistic director Terry McCabe, who also directed Hauptmann’s world premiere at Stormfield Theatre, and has directed it several times since, including at Victory Gardens, calls it his favorite play. In his loving current production, George Seegebrecht gives a fascinating performance in what is undoubtedly an early work, but one which remains as rich and complicated as ever.

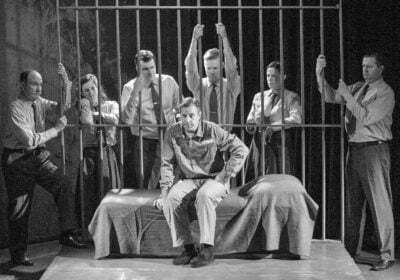

Bruno Richard Hauptmann (Seegebrecht) is awaiting execution for the kidnapping and death of Charles and Anne Lindbergh’s infant son. He still maintains his innocence, but the whole country is crying for his blood. With nothing left to fight for but his posthumous reputation, Hauptmann implores us to hear his side of the story. He claims that it will show he was just an ordinary immigrant who had nothing to do with the case, until he was arbitrarily swept up by police and prosecutors who just wanted a scapegoat, and picked him because he was German. The six guards appear at various points in his narrative as the other characters, but they don’t always perform the roles he creates for them without resistance. Near the end of the first act, they pressure Hauptmann to act out the kidnapping the way the tabloids have described it, for the audience’s lurid curiosity as much as to provide evidence in the case.

A program note states that the information Hauptmann supplies in the play about the planted and faked evidence at his trial, the pseudo-scientists presented by the prosecution as experts, the beating he endured in police custody, and the unfair budget disparities between the defense and prosecution is true. The play and production are sympathetic to him, and Seegebrecht’s performance does not give any obvious signs of the character being anything other than a frustrated, frightened man who is using a mixture of stoicism and irony to cope with injustice. However, the play does not remove all doubt about Hauptmann’s guilt. Brian Pastor plays an oily prosecutor, of exactly the sort who is usually a one-dimensional villain, except that he is able to provoke a complete meltdown from Hauptmann on the stand. The defendant has no good explanations for the circumstantial evidence against him, and the ones he gives are extremely fishy. Most notably, he was in possession of a large share of the ransom money and the contact information of Lindbergh’s go-between. Following this scene, we are forced to see him in a new light, and start questioning everything.

Aware now of how unreliable Hauptmann’s narrative is, we see the other characters anew, and notice more when the guards who are playing them acquiesce to Hauptmann, and when they contradict him. McCabe has assembled a strong ensemble, who, without any change in costume, are able to clearly differentiate between their characters. Our understanding exact character of Jerry Bloom’s Dr. Condon, who volunteered to be the go-between, changes with who is being quoted, without Bloom needing to alter himself at all. Ryan David Heywood’s Charles Lindbergh has something unsavory about him, even though even Hauptmann can find nothing to criticize in his conduct under the extremely difficult circumstances (it is likely that part of the modern debate over Hauptmann’s guilt is motivated by peoples’ resentment of Lindbergh’s racism and isolationism during World War II, and their desire for Lindbergh to have been wrong about unrelated matters). Robert Kaercher, Sheila Willis, and Kat Evans also appear as the judge and Hauptmann’s and Lindbergh’s wives, respectively, and Evans especially deserves praise for her ability to switch between the demure, frightened Mrs. Lindbergh and a hardened prison guard.

As is clear from this play’s proximity to Never the Sinner in Logan’s career, the justness of the death penalty was weighing on his mind at the time. Whereas Never the Sinner challenged the morality of the death penalty even for people who were undoubtedly guilty of the most heinous crimes, Hauptmann focuses on the possibility of a wrongful conviction and the danger of giving power over life and death to governments that can never be totally purged of corruption and misconduct. However, the case is also different in that everyone agrees that, whoever the kidnapper or kidnappers were, they probably did not intend for the baby to die, and that Hauptmann was executed and Leopold and Loeb weren’t is itself a major flaw in capital punishment. The play’s exclusive focus on Hauptmann is a limitation in that, for the most part, he has only the audience to play off of, but Logan still depends on the other characters coming in to provide ambiguity. In the past thirty years, there have also been several pro-Hauptmann publications, making its sympathetic portrayal of him less provocative, and death penalty supporters have crafted responses to concerns the play raises. However, as an investigation of a character and his dreadful circumstances, and an opportunity to display skilled acting and an atmosphere of intrigue, Hauptmann’s mystery remains as potent as ever, and City Lit fans especially will enjoy McCabe’s most heart-felt work.

Recommended

Jacob Davis

Reviewed June 7, 2016

This show has been Jeff recommended.

For more information, see Hauptmann’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing at City Lit, in the upstairs at 1020 W. Bryn Mawr Ave, Chicago. Tickets are $29, with discounts for students, seniors, military, and groups. To order, call 773-293-3682 or visit citylit.org. Performances are Fridays and Saturdays at 7:30 pm and Sundays at 3:00 pm through July 10, with additional performances at 7:30 pm on June 30 and July 7. Running time is two hours and ten minutes, with one intermission.