Head of Passes at Steppenwolf Theatre Company

By Tarell Alvin McCraney

Directed by Tina Landau

Produced by the Steppenwolf Theatre Company

Tarell Alvin McCraney’s achingly lyrical new play pushes one’s faiths to the utmost limits.

Tarell Alvin McCraney’s new play Head of Passes—now playing at the Steppenwolf Theatre under the direction of fellow company member Tina Landau—is a powerfully charged mytho-poetic meditation on the power of faith, prayer and letting go.

At her home in the Head of Passes—that swath of southern Louisianan swampland where the Mississippi opens out into the Gulf of Mexico—the widow Shelah’s friends and family have gathered together to celebrate her birthday. Yet unbeknownst to anyone beyond her family physician, Dr. Anderson, Shelah is gravely ill, the knowledge of which is pushing this aged woman to the very edge of health and sanity. Still, not even her encroaching illness can prepare Shelah for the trials and tribulations that await her as the Louisiana rain promises to wash away more than she’s otherwise willing to give. Without revealing too much the calamity that rains down on Shelah’s head, let’s just say that Head of Passes is inspired by the Book of Job, and consequently, holds nothing back.

Though make no mistake about it. Shelah’s misfortunes do not result from anything that she has done, but rather from what she is, namely human—tragically all-too-human. In this way, Head of Passes borrows from the existential nightmares of Franz Kafka, especially his 1925 novel The Trial, which tells the story of a man arrested and prosecuted by a remote and inscrutable authority without ever being informed of the nature of his crime. The Trial—itself a veiled commentary on the Book of Job—finds definite reverberations in Head of Passes, with Shelah struggling to justify her immense grievances to a God equally as impervious and cold as anything in Kafka’s imagination.

Yet where McCraney deviates most from this received inheritance is in a certain positive inflection of the human spirit and an ardent belief that prayer itself—even more so than God—manifests the beliefs that hold us. “Hold onto me, Lord,” Shelah intones. “The love of light is holding me.” For Shelah, prayer is self-sustaining and an ardent manifestation of her desire for more life. Strident secularists will no doubt take exception with this, insisting that McCraney’s portrait of faith lacks the requisite irony we have come to expect from “serious” theater. But as the Christian existentialist Soren Kierkegaaard once wrote, “It is human to lament, human to weep with them that weep, but it is greater to believe, more blessed to contemplate the believer.” And McCraney’s play is nothing if not a blessed contemplation of the believer.

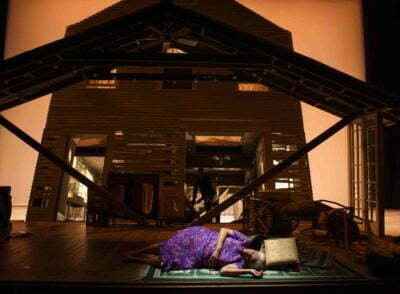

Structurally speaking, the first act begins in the entrenched conventions of a standard “kitchen sink realism.” There’s the seemingly innocuous occasion of a birthday party, the gathering of friends and family in a quaint living space, and the dialects that feel specific to the time and place in question. Nothing, in other words, that would be out of place in a mid-twentieth century social drama. But in Head of Passes, such standard realist conventions are soon turned on their heads as the second act careens into something more symbolic, ritualistic and mythological. There’s the subtle invocation of Greek tragedy in the use of “messengers” to relay calamitous events, the creation of ritualistic space with stones, the use of spirituals to artfully disrupt the narrative, and the whitewashing of the stage in stark light to accent the elemental dimensions of Shelah’s suffering. This gradual transition in Head of Passes from realism to something symbolic provides McCraney a solid bedrock of plausibility from which the mytho-poetic can believably emerge.

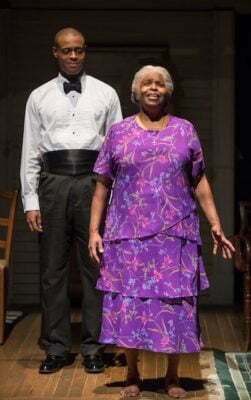

Needless to say, the success of this transition is highly dependent on the performance of McCraney’s leading lady. Thankfully, Cheryl Lynn Bruce as the widowed matriarch Shelah is a revelation, keeping well apace with the broad emotional and spiritual arcs that McCraney sets her on over the course of the play and delivering one of the most inspired acts of self-healing you are likely to see on stage. And Tina Landau’s deeply sensitive direction successfully is well-paced and attuned to the unique formal challenges posed by McCraney’s play. And David Gallo and Collette Pollard’s scenic design—which includes the remarkable onstage collapse of Shelah’s home—is as technically dazzling as it is emotionally resonant.

In brief, Head of Passes is an ambitious and boldly lyrical examination of faith and the power of prayer. For unlike the more placating sentiments of a standard Sunday sermon, McCraney’s sense of faith is not easily won but rather forged in the depths of misery, and it is a sense of faith from which not even the strident doubter is excluded. For as Kierkegaaard said, “Faith is the highest passion in a man. There are perhaps many in every generation who do not even reach it, but no one gets further.” In this sense perhaps, Head of Passes pushes us all to our limits.

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

Anthony J. Mangini

Reviewed Thursday, April 11th, 2013.

Running time is approximately 2 hours with one intermission.

Head of Passes runs until June 9th, 2013. Steppenwolf Theatre is located at 1650 N. Halsted Ave, Chicago, IL 60614. For tickets call Audience Services at (312) 335-1650 or at www.steppenwolf.org. Check out their Theater in Chicago listing at https://www.theatreinchicago.com/head-of-passes/5444/

.