He/She

Frauenliebe und Leben

Composed by Robert Schumann

The Diary of One Who Disappeared

Composed by Leo Janáček

Produced by Chicago Opera Theater

At the Harris Theater

With her in my arms I defy the morning

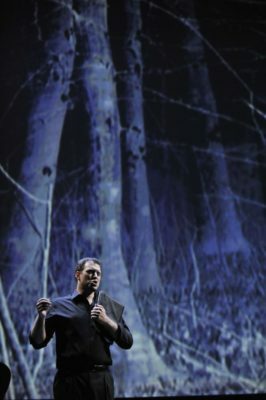

Chicago Opera Theater offers us, with this concert, a chance to see two stunning chamber pieces, one composed by Romantic Robert Schumann, the other composed by the more modern, Czech composer Leo Janáček. The only accompaniment is a piano, and the only set is a screen with projections. And they are intimate and beautiful – even when the overall production asks the audience to draw comparisons between the pieces that seem a stretch.

The first piece performed is Schumann’s Frauenliebe und Leben, a song cycle based on the poems of Adelbert von Camisso. Craig Terry on the piano and the Mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnson Cano create sorrowful, sentimental, and joyous music, with the lyrics and images projected sparingly, helping to set the mood. It is music to fall in love to – and it embraces all the happiness and deep, lasting pain that love brings. The passion with which Ms. Cano sang, and the deft care with which Mr. Terry played, convey all the emotions to their head; lyrics like “help me, sister, with my wedding dress” brought the audience to their knees.

The first piece performed is Schumann’s Frauenliebe und Leben, a song cycle based on the poems of Adelbert von Camisso. Craig Terry on the piano and the Mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnson Cano create sorrowful, sentimental, and joyous music, with the lyrics and images projected sparingly, helping to set the mood. It is music to fall in love to – and it embraces all the happiness and deep, lasting pain that love brings. The passion with which Ms. Cano sang, and the deft care with which Mr. Terry played, convey all the emotions to their head; lyrics like “help me, sister, with my wedding dress” brought the audience to their knees.

If Schumann’s piece makes you want to fall in love, Janáček’s piece makes you want to consummate it. The story of a young man who falls in love with a gypsy, meets her clandestinely, and eventually leaves his family to be with her and his child, The Diary of One Who Disappeared is refreshing, modern, and vivacious. Love for the young man in this opera is difficult, full of sin and remorse, yet thrilling, life-affirming, and ultimately fulfilling. Tenor Joseph Kaiser gives a wonderful performance, and the Gypsy, Brandy Lynn Hawkins, seduces purely through her voice.

If Schumann’s piece makes you want to fall in love, Janáček’s piece makes you want to consummate it. The story of a young man who falls in love with a gypsy, meets her clandestinely, and eventually leaves his family to be with her and his child, The Diary of One Who Disappeared is refreshing, modern, and vivacious. Love for the young man in this opera is difficult, full of sin and remorse, yet thrilling, life-affirming, and ultimately fulfilling. Tenor Joseph Kaiser gives a wonderful performance, and the Gypsy, Brandy Lynn Hawkins, seduces purely through her voice.

Taken individually, these pieces are little marvels, mirabile visu. Taken as a set, as the designer presumably wishes us to do, they don’t quite work. The production, as a whole, seems to say things about gender roles it may not necessarily want to: the woman is passive, purely memory, this distant thing with no sex drive; while the man is all present, all action, all bright colors and primal urges. The woman in the man’s piece is seen through this lens alone. Granted, this is how woman was idealized in Schumann’s time, and the passion of the young man was rustic and new in the time of Janáček; but can’t we take these pieces, as they are, at face value? Do we have to call the program He/She (with He going first, even though She first sings), instead of simply taking them piece by piece? That said, that is a quibble with the direction of the production, not the music, performers, or backdrops themselves. These are wonderful pieces of music that make for a somewhat brief and immensely enjoyable evening.

Taken individually, these pieces are little marvels, mirabile visu. Taken as a set, as the designer presumably wishes us to do, they don’t quite work. The production, as a whole, seems to say things about gender roles it may not necessarily want to: the woman is passive, purely memory, this distant thing with no sex drive; while the man is all present, all action, all bright colors and primal urges. The woman in the man’s piece is seen through this lens alone. Granted, this is how woman was idealized in Schumann’s time, and the passion of the young man was rustic and new in the time of Janáček; but can’t we take these pieces, as they are, at face value? Do we have to call the program He/She (with He going first, even though She first sings), instead of simply taking them piece by piece? That said, that is a quibble with the direction of the production, not the music, performers, or backdrops themselves. These are wonderful pieces of music that make for a somewhat brief and immensely enjoyable evening.

Highly Recommended

Will Fink

Reviewed on 5.7.11

For full show information, visit Chicago Opera Theater’s website.