Jake’s Women

By Neil Simon

Directed by Skye Robinson Hillis

Produced by Spartan Theatre Company

At Royal George Theatre, Chicago

Neil Simon’s Journey Inside the Mind

Choosing plays wisely is crucial to any theatre, and particularly ones just starting out. Therefore, I’ve been thrilled by the choices of Spartan Theatre Company, a young itinerant group, which came to my attention last year with their excellent revival of Tony Kushner’s first professionally produced play, A Bright Room Called Day. For their current production, they’ve once again reached into the past for a lesser-known work by a well-known master, Neil Simon’s Jake’s Women. Simon’s writing in this script is not only stylistically elegant, but a complex examination of the craft of writing itself. The small upstairs space at the Royal George provides an appropriate setting for the interior of a neurotic, borderline-psychotic, creator’s mind.

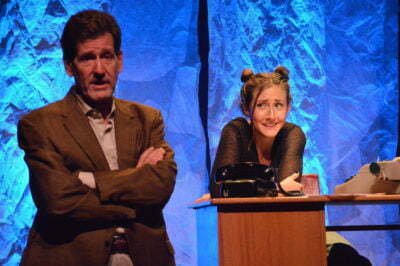

Jake (Brian Rooney) is a successful middle-aged writer of fiction. We first see him banging away on a typewriter (Simon’s script wisely only specified “word processor,” but director Skye Robinson Hillis has kept the play in the early 90s, when it was written), when he is interrupted by a call from his sister, Karen (Lisa Herceg). An insecure and lonely divorcee, Karen wants to confirm they’re having dinner together, and asks what Jake’s writing. “I don’t know what I’m writing, I haven’t read it yet,” he snaps. Jake’s creative energies are mostly being taken up by imaginary conversations with the women in his life, which he regards as a kind of writing. The first of these we see is with his much younger wife, Maggie (Kelly Levander). He has her recount the time they first met, which comforts him, because he’s sensing trouble in their present-day relationship, and plans to confront her tonight for having an affair. The problem is, Jake’s too smart a writer, and knows women too well to imagine them saying what he wants them to. When he conjures Karen shortly later, she admonishes him for giving her bad lines, and forces him to admit he had an affair, too.

Maggie proposes a trial separation. Despite Jake’s pleas that living together temporarily will only lead to permanent estrangement, Maggie insists that they need a chance to reconsider their lives together. She had a conservative religious upbringing that she’s been rebelling against by focusing on her career to the exclusion of her marriage, and he has trust issues, which lead him to interact with fantasy versions of people more easily than with real ones. Though he’ll only admit it to the audience, Jake won’t (and therefore can’t) fully control the apparitions, the most frequent of whom is his deceased first wife, Julie (Haylee Burgess). He’s talked to the imaginary version of his therapist, Edith (Anne Marie Lewis) about it, but he won’t listen to her advice, even though he’s the one imagining her giving it to him. But six months after Maggie’s been gone, Jake’s imaginary conversations are becoming much less benign. Though he doesn’t totally lose the ability to distinguish the real and imaginary women, he argues with the imaginary ones in front of real ones, and then argues with the imaginary ones about whether he’s still really in control, or just scape-goating them by telling himself he’s crazy.

To help keep the audience clear on what’s happening, the stage is bisected into Jake’s office, and the living room. On the back wall hang indistinct bolts of papery cloth, which are illuminated in different colors when the apparitions are onstage (lighting design by Joseph A. Burke and Brendan Meyer). This is a strong choice on Hillis’s part, because keeping the audience aware of what is and isn’t real allows us to focus more on the content of the dialogue, instead of worrying we’re being tricked. Since we know who the real Maggie is, the version of her that’s really Jake trying to come to terms with himself is easier to accept. There are other clues besides the lighting, though. In Jake’s fantasy, Maggie is always eloquent and witty, but the real one sometimes confuses word-order when she’s flustered. The imaginary one even acknowledges she’s better-spoken in his mind, and then ridicules him for the self-flattery of having her say that.

The complexities of playing a character who is a fragment of someone else is a challenge for the actresses, which they rise to brilliantly. I especially enjoyed Maya Hlava’s cute, but straightforward, performance as the twelve-year-old version of Jake’s daughter, Molly (who is played as an adult by Jill Karrenbrock). Haley Burgess manages to play Julie as both a teenager and a thirty-five year old convincingly; they not only seem like the same person, but each also is informed by Jake’s older perspective, and her conversation with Karrenbrock is the play’s sweetest moment. Levander’s Maggie is a coil of nervous energy in flashbacks, and oppressed by mounting dread but possesses great clarity of purpose in her scenes in the present reality. As Jake, Rooney’s overactive mind and endless loops of reflections are pushing him to the breaking point, but he’s such a charismatic, skilled speaker, that he remains fascinating even while he’s ignoring and contradicting his subconscious.

All around, Spartan Theatre has a wonderful production of Jake’s Women, in which they uphold their mission statement by sticking to a tiny budget, and focusing on acting. This is especially impressive because Spartan’s artistic directors are both currently engaged elsewhere. I should point out, in case it isn’t obvious, that the play is highly cerebral. While examining his motivations, Jake recounts lots of strong feelings, but his frequent use of direct address, and the self-awareness of the imaginary women, creates a distance between him and the audience, emotionally, at least. Physically, the Royal George’s upstairs is quite small, which partially makes up for the play’s wryness. The ultimate source of Jake’s dysfunctionality turns out to be mundane, but Simon’s skill at writing Jake’s self-psychoanalysis is a rare treat.

Recommended

Jacob Davis

Playing at the Royal George Theatre, 1641 N Halsted St, Chicago. Tickets are $20, with discounts for industry and students; to order, call 312-988-9000. Performances are Fridays and Saturdays at 7:30 pm and Sundays at 3:00 pm through October 11. Running time is two hours and twenty minutes, with one intermission.