John Marin’s Watercolors: A Medium for Modernism

The Art Institute of Chicago

January 23rd – April 17th, 2011

The Art Institute is staging over 100 works of the acclaimed American watercolor artist John Marin (1870-1953). Know this…watercolor works are fragile and they don’t get to see the light of day as much as you’d like. For those who may have missed Winslow Homers exhibit at The Art Institute back in 2008, you have a chance for redemption, albeit in a window that is a little more than a month in size.

An architectural draftsman, John Marin abandoned the world of precision drawing and enrolled into the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia to pursue a career as an artist. In 1905, like many aspiring artists at the time, Marin traveled to Europe to seek inspiration. During his five year stay, primarily in Paris, Marin utilized his draftsmanship skills, etching detailed reproductions of famous landmarks and selling them tourists. Eventually Marin started tinkering with watercolors, creating impressionistic paintings of Euro-Vistas such as the Austrian Tyrol. Inspired by Whistler, Cezanne, and Matisse, Marin’s European paintings, and future works, contain the Fauvist and Impressionistic influences of his heroes.

Marin was clearly absorbing Europe, but it wasn’t the electricity flowing through it’s early 20th century art scene that altered Marin’s course as a commercially successful artist. Rather it was his encounter with photographer Edward Steichen. Steichen, a modern-art scout for the influential New York art dealer Arthur Stieglitz, discovered Marin and sent some of his works to Stieglitz’s studio. Stieglitz (the husband of artist Georgia O’Keefe) not only played an integral part in brining Marin’s art to the forefront of the New York art scene, he also consulted him on innovative ways to paint and frame his work, and eventually becoming one of his greatest champions. In fact, Stieglitz once suggested to Marin that he should break himself from conventional landscapes forms and be more “free” with his brush implementing more abstract and interesting interpretations of nature, which was the key to Marin’s popularity. Despite being in total accord with this ideal, Marin would state that he already started doing so before Stieglitz’s suggestion.

Returning to the states permanently in the fall of 1910, Marin would use the rest of his 43 years on Earth to produce a large and significant oeuvre that would alter the notions of watercolor painting as it was known and how we know it today. Marin would spend time painting in New York, New Mexico, and ultimately settling in his most favorable environment, the remote coasts of Maine. Marin was always inspired by the life force of nature, and how we as humans, or artists, coexist with it. To Marin, nature was full of metaphors. (Pine trees for example reoccur in many of Marin’s paintings as symbols of survival.) Everything Marin painted breathed, even his famous paintings of inanimate buildings, bridges, and cityscapes. But it was Marin’s unique process of painting that made his works truly innovative. Hard edges, abstract line composition, and sometimes totally blank space, branded Marin as a common modern artist, however, his thick swathes of graphite, crayon, ink, and charcoal wrapping vibrantly blotted and brushed watercolors, sometimes applied directly on the paper, made Marin an innovator, shattering the conventions of how watercolors were produced. Despite the chaos and noise of his composition, and the unique colors built from his palette, Marin was able to split the difference by adding soft peripherals and a “one with nature” worldview to make his works as soothing as they are thought provoking.

The Medium for Modernism exhibit, located in the space normally reserved for the Art Institute house prints and drawings near the main entrance off to the left, is divided up into 7 main categories. (The Impact of Europe, Return to the United States, New Mexico, Marin’s New York, Marin/Stieglitz/O’Keefe, The Border of the Sea: Maine, and the final years of Marin’s life on Cape Split (also in Maine) The flow of the exhibit is not so much chronological as it is sequential. Meaning, that Marin worked in a sequence based on his mood and that the paintings are changing from genre to genre at whiplash speed. At first I was confused by this layout, getting lost and going out of order with my audio tour guide. Yet the longer I was there, the more I appreciated, and understood the contrast. The abstract mixed with the realism, the bold mixed with the light, and the city mixed with nature…all themes that are opposites, yet all working for the same ideal. This constant state of comparison and juxtaposition is the true reward of the exhibit.

Compare and Contrast: Nature: Cape Spilt:

In 1933, Marin and his family moved to an isolated portion of Maine, called Cape Split. It was here where Marin would die at home some twenty years later. Marin found Maine to be a constant source of joy, not just for painting but for boating and observing nature as well.

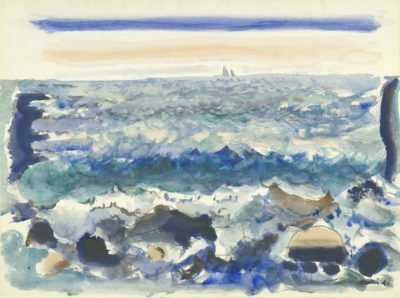

Cape Split, Maine, 1941, painted 7 years after Marin’s settling to Cape Split, is an optimistic watercolor of a gentle Atlantic Ocean. Dark blue blots form the jagged rocks below as they transform into a vignette of water that grows lighter and lighter into the distance, brining your focus to the faint outline of a sail boat, contently parked in the middle of the ocean. Two lines, one blue one light pink, represent the sky giving way to a storm that could be, but isn’t quite yet. Marin would take his time searching for the best perspective in which to paint, even if it meant negotiating treacherous branches and rocks to get closer to the coast line. Marin produced this at 71 years old, telling the viewer he’s not only capable of getting tangled in nature, but he is still very interested as well.

On the other side of optimism is a more looming painting entitled Approaching Fog, 1952, painted one year before his death. At this time Marin is dealing with the loss of his wife and is perhaps starting to ponder his own mortality. This could have very well been the same exact location he painted Cape Split, but with a darker point of view. Built mostly in shades of gray, the sea is unsettled and undefined, with the sensation of rain distorting the peripheral of the coast. The once blue and pink “sky lines” from before are replaced shades of gray and one thin, single line of black. Still, there is hope. Small dabs of blue and sea foam green peak through the water with thin black lines playing near the coast, creeping up on the rocks. If Cape Split is bright, optimistic, and warm, Approaching Fog would be its photo negative.

Compare and Contrast: The City: Marin’s New York:

During Marin’s 5 year trip to Europe he utilized his architectural draftsmanship skills to draw highly detailed pictures of famous European attractions, only to end up selling them to tourists. No greater example of the painstaking detail Marin took with these etchings than L’Opera Paris c.1908. We can see that Marin is working at a masters etching level with details that are too numerous to count, yet he’s is trying to work into his own. Minute spaces in between the opera goers become larger and larger until they fade away into the bottom of the picture. (Disappearing edges and blurry peripherals reoccur in many Marin’s works.)

Later on during several formative years in New York, Marin would revisit his etchings skills and create a large of amount of skyline drawings. Much like his spirit filled depictions of nature Marin meticulously etched Woolworth Building (The Dance) 1913. Back laid on an ominous sky, not unlike an unsettling storm at sea, the buildings are flexible and alive with the wind blowing them in opposite directions of the trees in the plaza. The detailed perspective is so authentic you feel as if f you were trying to look up while picking up your hat. Again, we see the marriage of the inanimate concrete and steel moving in harmony with the “real” life of the trees.

Right next to the Woolworth Building, hangs the Sketch of Lower Manhattan 1917, an extremely reduced, abstract view one of the busiest places in the world. Done fours years after Woolworth Building, Lower Manhattan is another paradox that Marin seems to be having fun with. No more than twenty or twenty-five lines occupy the paper. Sharp, unfinished blocks float below an outlined spire. It’s as if Marin is growing tired of the hustle and bustle of an ever growing New York City. Perhaps, the population has become so dense that there might as well not be anything there at all.

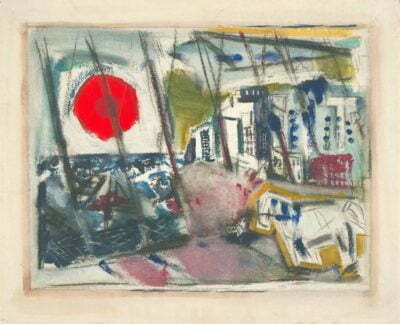

Of course you would be at a loss if you didn’t at least take the time to see Marin’s more well-known works such as Movement: 5th Ave., 1912, Red Sun Brooklyn Bridge, 1922, and The Pine Tree. Small Point Maine, 1926, (all great examples of Marin’s balance of whimsy and hard lined modernism), however, it would be equally disheartening if you didn’t try to step back and consider Marin’s work as a whole, noticing the paradox of his whimsy and hard lined modernism. The exhibit doesn’t cost you extra, so you can parcel it off piece by piece during your visit or devour it whole. In any case be sure to catch it while you can, because once major watercolor exhibits like this leave, they’re not guaranteed to be back anytime soon.

Highly Recommended

John B. Reinhardt

3/12/10

The Art Institute of Chicago / Running thru January 23rd – April 17th, 2011/ Monday–Wednesday, 10:30–5:00 Thursday, 10:30–8:00 Friday–Sunday, 10:30–5:00 /Admission

Adults: $18 Children, Students, and Seniors (65 and up): $12Children under 14: Free

Members: Free