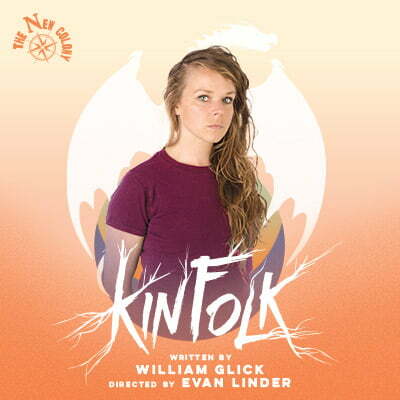

Kin Folk

By William Glick

Directed by Evan Linder

Produced by The New Colony

At The Den Theatre’s Upstairs Main Stage

You Can’t Choose Your Family, But You Can Choose Your Otherkin

After seeing The New Colony’s last show, admittedly, I was not anticipating seeing their current, collaborative production Kin Folk, written by William Glick, especially because its subject matter doesn’t appeal to me. Surprisingly, however, I found the show rather enjoyable. Granted, there are many missteps production-wise (e.g.awkward stage design, poor execution of projections, sloppy lighting); yet The New Colony, under the direction of Evan Linder, puts their attention to where it truly matters: into a very strong cast. And though the story is sometimes confusing and, to me, ambiguous as to its meaning, it too raises some curious questions as to what it means to be human and how sometimes the gap between who we are and who we want to be cannot be bridged.

Sitting down to dinner in the quiet suburb of Naperville, Lucy (Annie Prichard), to all appearances, is an unexceptionally ordinary young woman. And as her two sisters, Mary (Elise Spoerlein) and Eleanor (Alexia Jasmene), and her husband, Toby (Chris Fowler), enthusiastically discuss the idea of Eleanor’s YouTube “coming-out as trans” video and the immediate prospect of them all moving to Chicago, Lucy seems even more ordinary and distant, withdrawn in the corner of the table and staring longingly out the window.

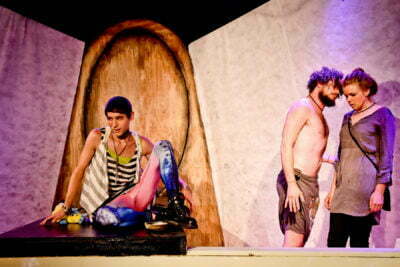

However, what Lucy’s family doesn’t know (yet) is that, under cover of night, Lucy meets with Arethin (Steve Love), a self-identifying elf, and performs rituals in order to stir the “awakening” of her true, self-actualized self: a dragon named Kreeka. That same night, to move along Lucy’s awakening, Arethin introduces Lucy to Blubberwort (Andrew Hobgood), a giant gnome who lives in the avatar of a human mortal, and who also happens to be the moderator of an online-community website of Otherkin (other people who identify as fantastical creatures). After some persuasion (i.e. torture), Lucy convinces Blubberwort to allow her to join the website and Lucy’s journey to self-actualization really takes off.

As Lucy begins growing into the Otherkin community and corresponding with a werewolf named Dusk (Stephanie Shum), Lucy finds her “real” family quickly abandoning her. Not surprisingly, they all exhibit varying degrees of intolerance towards her coming-out dragon, ranging from confusion to personal offense: apparently there’s a limit to one’s goodwill acceptance of another’s subjective beliefs.

Yet, as Lucy becomes more and more absorbed in her identity as a dragon, even her closest Otherkin allies, Blubberwort and Arethin, drift away, until she’s left all alone in Naperville with nothing but her fantastical, online relationship to Dusk to comfort her. That is, until Dusk finally makes the trip out to meet her, and then even Lucy must confront the limits of her bodily, human existence and her suspension of “reality.”

The theme of “identity,” which stretches like a dragon’s tail through each scene of Kin Folk, also comprises the arcs of the other characters. Eleanor wrestles with the unavoidable obstacle of her physiognomy; Mary (or Mary-Beth, as she goes by on YouTube) struggles to be the warm-hearted and family-focused woman that she presents herself as in her copious YouTube videos on homemaking; and Arethin abandons his elf lineage when he finds himself more akin to the Otherkin troll community.

Blubberwort and Dusk, on the other hand, are more comfortable with their identities. Blubberwort is a true believer in his avatar philosophy and confronts Mary with the admission that, essentially, he is what he is and is not trying to be strange or different. Dusk, conversely, is unabashedly lesbian and more-or-less views her werewolf identity as something that does not override or negate her human form or desires.

In regards to Lucy and Toby, however, the issue of identity is a bit more ambiguous, and herein lies a confounding ambiguity of William Glick’s script. Toby is depicted as a very devout Christian, and, though he continually implores Lucy to attend worship with him, he is faithful and tolerant of her dragon-identity up until the point where she attempts to sodomize him with an eight-inch dragon phallus (i.e. a purple dildo) during sex. Understandably, he is shaken. The moment he hands Lucy his wedding ring he begins his true “crisis of faith,” which culminates in another scene with Eleanor, in which, after encouraging her trans journey, Toby denies her romantic advances and she denounces him: “I thought you were different.” How exactly we are to understand this moment is incredibly puzzling to me, as it was clear that Toby was not “coming-on” to Eleanor and there didn’t appear to be any indication to me that Toby was either a superficial or hypocritical Christian—at all. In any case, the next and last time we see Toby he’s praying to God, lamenting how, despite his religious desire to, he no longer feels Him in his life. Is this, too, meant to be a crisis of identity? If it is, it doesn’t come through clearly in the performance.

Yet, while the ambiguity of Toby’s story can be overlooked as an inconsequential hiccup, the ambiguity of Lucy’s arc seems highly problematic. After having to confront the romantic fantasy she was living in with Dusk (she thought Dusk was a dude), Lucy again finds herself in her home in Naperville with her two sisters, who yet again show little care for Lucy’s obviously depressed mood. Things have returned to their boring status quo, and Lucy casually fishes for some sympathy by remarking that she feels “so ordinary.” Well! Eleanor puts her in her place: for Eleanor, “ordinary” has been the sole object of her life project, and only through her sexual and gender transition has she been able to taste its graces. Lucy simmers down, and the last image we see is Lucy spreading her arm to reveal a—real? imaginary?—dragon wing.

But the question remains: What exactly is Glick saying? If we are to suddenly interpret Lucy’s story as that of a person seeking to feel special and appreciated, does that not at the same time call into question (and potentially delegitimize) the identity crises of the other characters—in particular, Eleanor, Arethin, and Blubberwort? Or, does he mean to pose the question of our inability to mediate the subjective nature of such crises—that we simply cannot determine the validity of any such claim to be this or that, in actuality? Or, is this just a vague and sloppy result of a collaborative effort? In any case, I did find the conclusion provocative, and I personally identified with Lucy’s desire to feel special (though not her desire to be dragon).

Though there is obviously much to ponder philosophically in this play, I would not say its strength lies in its subject matter or writing. Rather, what kept me captivated, and what I believe others will likewise find captivating, are the performances. Steve Love’s transition as Arethin from elf to troll may sound like a silly concept, but the dramatic shift he undergoes in not only his voice and appearance but his demeanor is jarring and strangely moving. Andrew Hobgood plays a loveable, good-natured Blubberwort with natural humor and finds many moments of endearing tenderness in his character. And Elise Spoerlein as the outwardly abrasive yet inwardly conflicted Mary(-Beth) shines in her many comedic moments and even manages to elicit sympathy in her moment of candid confession (despite it having to be drawn out of her by Glick in a self-disclosing monologue).

However, without reservation, most notable among the performances was that of Annie Prichard. In an interview last year, Prichard remarked that she brings “all of [herself]” to her work; after witnessing her performance as Lucy, that statement can be undeniably attested to. If I had not absolutely believed every moment of brimming desperation, aggressive vulnerability, and wholehearted dedication with which she attacked every word and action on the stage, this play would have been over at the first mention of “dragon.” It is no small feat of theatre-magic to find oneself so captivated by a performance that one is willing to believe in something as patently absurd as a “self-actualized dragon kin.” Annie Prichard pulls it of spectacularly.

While I can sympathize with those who will be turned-off by its subject matter and its obvious appeal to “the younger generation,” Kin Folk does offer more than just what it advertises—in fact, its description is rather misleading, as I wouldn’t say Lucy learns how to “live a life driven by faith and love of the fantastic.” Rather, this is one New Colony collaborative effort that succeeds in showing some of the human grit and ambiguity of life. If you’re willing to get lost in a some very strange circumstances with some very strong performances, then you might find some kinship in Kin Folk.

Recommended

August Lysy

Reviewed on 12 July 2016

For more information, see Kinfolk’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing at The Den Theatre’s Upstairs Main Stage, 1333 N. Milwaukee Ave., Chicago. Tickets are $20 – $25, with 25% discounts for students and seniors. For tickets and information, visit TheNewColony.org. Performances are Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays at 7:30 p.m., and Sundays at 3:00 p.m. through August 14th. Running time is 85 minutes with no intermission.