Never the Sinner

Directed by Gary Griffin

Produced by Victory Gardens Theater, Chicago

Where Humanness and Monstrousness Intersect

It is a very good sign for a young playwright if their first work is as good as John Logan’s Never the Sinner. Not that the earliest version of Logan’s recounting of Leopold and Loeb’s twisted relationship bore much resemblance to the current script being performed at Victory Gardens, which also performed it in 1995, but it did demonstrate his meticulous research and fascination with character dynamics. Part docu-drama and part historical fiction, the play expands defense attorney Clarence Darrow’s questioning of whether the world really understood the two young murderers well enough to claim the moral authority to hang them. There are a number of ethical issues the script explores, but in the hands of director Gary Griffin and his leading actors, the play remains grounded in the humanity of two people the rest of the species still prefers not to be associated with.

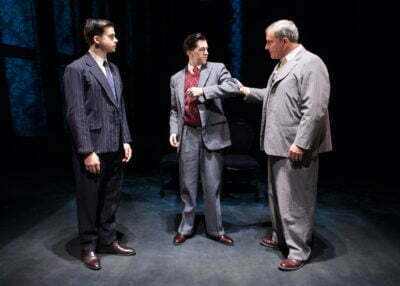

In 1924, two teenage University of Chicago students, Nathan Leopold (Japhet Balaban) and Richard Loeb (Jordan Brodress), were arrested for the murder of Loeb’s cousin, fourteen-year-old Bobby Franks. The two were intellectually gifted and came from rich families, but on the advice of their lawyer, Clarence Darrow (Keith Kupferer), they pled guilty. The proof of their guilt was overwhelming, and Darrow’s concern was not getting them acquitted, but sparing their lives. Using his famous rhetorical skill, Darrow transformed the sentencing hearing into a sort of trial for the death penalty itself. The guilty plea was legally an admission of sanity, but for over a month of hearings widely covered in the media, Darrow brought in psychoanalysts and child-development specialists to examine his clients, and cast doubt on the legal distinction between sane and insane, while hoping that if the world new his clients better, they would be judged less harshly.

In their vast reading, Leopold and Loeb discovered the works of Friedrich Nietzsche and his concept of a “superman,” a person whose intellectual superiority grants him the authority to overturn outdated moral values, which they believed described themselves. They also thought killing somebody and getting away with it would be fun, and picked Bobby Franks basically at random. Leopold is studious, icy, and romantically obsessed with Loeb, who calls him “Babe.” Loeb is playful, impulsive, easily bored, and selfish. A psychoanalyst says they both have the emotional development of children, which is much more obvious with Loeb, but are quite lacking in empathy. He further states that between Leopold’s submissiveness and Loeb’s need for constant ego stroking, it was the interplay of their twisted personalities that made them far more dangerous and remorseless than they would have been otherwise.

Leopold and Loeb spend most of the hearings snickering, sneering, and outdoing each other in sarcastic quips. Loeb revels in the attention of his examiners and delusional fans, and happily prattles on about anything they want to hear. Leopold finds the examination scientifically interesting, and is a willing object of study. Both actors are terrific. Balaban’s Leopold is so restrained he appears nearly unfeeling but for his worship of Loeb, and even that he intellectualizes in moments of direct address. He expounds on his understanding of the superman idea with complete fanaticism, but a professorial air of dispassion. Brodress’s Loeb is reminiscent of Mark Hamill’s take on the Joker, only not as hammy. That’s meant as praise; while Logan has written Loeb to show a little vulnerability and perhaps even some concern about his parents and Leopold, much of the play’s theatricality comes from the boys’ gallows humor, which is slightly less offensive with the passing of time since Bobby Franks’s death. Loeb repeats a few times the first prayer he learned as a child: that his ignorance makes him an innocent. Both characters are awful, but I’m against consensus in that I’m more repulsed by Leopold, since even though Loeb can be amusing, he’s also so obviously dysfunctional, Leopold should have known better than to indulge him (which he even admits). It’s fascinating, and not just in a schadenfreude-kind of way, to watch them get thrown off their game as they survey all the lawyers, behavior specialists, and journalists, and realize that for the first time, they’re not the smartest ones in the room.

Bill Bannon, Celeste M. Cooper, and Demetrious Troy step in to play reporters and anybody else who is necessary in certain scenes. Cooper has a particularly fine moment of transformation while playing one of Loeb’s girlfriends. Gary Griffin has managed to work in the newspaper headlines, speculation, and editorials in a way that flows smoothly with the character analysis. Part of the reason the docu-drama approach works so well here is the Kurtis Boetcher’s wall-papered set avoids the trap of realism, and Michael Stanfill’s projections allow the faces of angry crowds to loom over the proceedings. But it’s also appropriate because of how often the characters themselves comment on the media-circus they are generating. As the prosecutor, Derek Hasenstab seems aware that since the case would have been a slam-dunk for him if it played out in the ordinary way, mugging for cameras can only hurt him. But he’s still happy to pile on the moral condemnation and outrage out of genuine feeling, and his final argument is as stirring as Darrow’s.

Keith Kupferer has the difficult job of finding reasons for Darrow to stay the course (other than that he’s being paid and has to uphold his reputation as a defense attorney, which isn’t dramatically as interesting). There are surely innocent people on death row he could be defending. What it comes down to, he claims, is a challenge to maintain higher moral principles such as “hate the sin, never the sinner,” and the unconditional value of human life, even in the face of ugly reality and the very people depending on him continuing to insult his beliefs. Just as Leopold and Loeb would not have committed the murder separately, Darrow’s whole strategy is to hope that the decision to impose the death penalty will weigh more heavily on a single judge than on twelve jurors. Since the case is a matter of historical record, most people know the outcome, but the debate is still current. It’s not just a matter of the death penalty itself, but of the nature of responsibility. At one point, the prosecutor concedes that he is asking a psychoanalyst to make an unscientific judgement. In large part due to this case, modern discourse surrounding criminal justice has changed a bit since Darrow’s day, but it remains fertile grounds for discussion. But the particulars of this story are interesting enough to stand on their own.

Highly Recommended

Jacob Davis

3jacob.davis@gmail.com

Reviewed November 13, 2015

This show has been Jeff recommended.

For more information, see Never the Sinner’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing at Victory Gardens Theater, 2433 N Lincoln Ave. Tickets are $15-60; to order, call 773-871-3000 or visit victorygardens.org. Performances are Tuesday at 7:30 pm, Wednesdays at 2:00 pm and 7:30 pm, Thursdays and Fridays at 7:30 pm, Saturday at 3:00 pm and 7:30 pm, and Sundays at 3:00 pm through December 6. Running time is ninety minutes with no intermission.