Penelope

Directed by Amy Morton

Produced by Steppenwolf Theatre Company

Finished, it’s finished, nearly finished, it must be nearly finished.

Many people – critics and audience members – are calling this play “boring.” It’s really wordy and there are long speeches and not a lot happens and what’s it about, anyway? Of course, people said the same thing about Beckett and Brecht. And since Enda Walsh is an Irish playwright who says himself that he’s been very influenced by the Germans, this makes sense. Indeed, it was commissioned for a German theatre. And there are definitely elements of Beckett and Brecht (among others) in his Penelope.

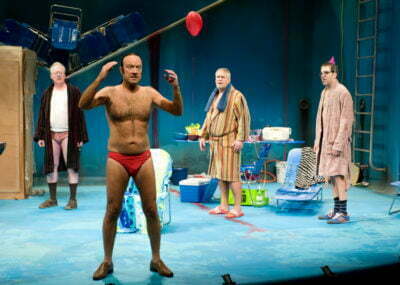

The play is a re-imagining of Homer’s Odyssey focusing on the suitors mooching off of Odysseus and wooing Penelope in his absence. Whereas in Homer’s version, they’re all still there when he comes home, Walsh has whittled his field down to four: out of the over 100 who sought Penelope’s hand, only four remain. So we have to ask ourselves: why these four? What about these last men has allowed them to outlast everyone else? Are these the last, best men, or are they the most hopeless, the most desperate, the primal, dark sides of humanity their primary characteristics?

Each man is distinct: the foppish wordsmith who’s filled with self-loathing and bile; the effete, weak intellectual; the whipping boy; and the alpha male, committed to the competition. They have decided to imprison themselves in the pool of Odysseus’ house (this is a sort of modern retelling), a self-imposed exile from the rest of the world. They gather each day, and each man is allowed an attempt to win Penelope’s heart, which brings us into the oddest conceit of the play: a camera turns on, and one man can then take the microphone nearby and say what he will to Penelope, who watches, secure, from a television inside the house. Each man takes a turn. In between they talk amongst each other; as it turns out, the previous night they’d all shared a dream of Odysseus returning and killing them. So they decide to band together, hoping one of them will win Penelope’s heart and this vision can be averted. So the question of whether fate can be avoided comes into play: if one of them is successful, could the vision be prevented? Or would it happen in any case?

I am of the opinion that, at the core of this play, it is about the redemptive power of love. Each man (save one) talks about starting over; Fitz (Tracey Letts) realizes that he’s wasted his life, he’s nothing, his center is hollow; but then, he says, at that center is also a will towards Penelope. He’s finally found something to give his life meaning, and it’s her. Dunne (Scott Jaeck) talks about a vision he’s having of gravity ceasing, and everything being flung off the Earth except for a ten-year-old him and his mother, in their small house, and their love begins the world again. Burns (Ian Barford) tells Penelope that he’s been a bastard his whole life, but through the love of a friend, he’s discovered what it means to be good and he wants to start over. The only one without a speech like that is Quinn (Yasen Peyankov), which is why he must end up as he does. Now, these are all essentially death-bed revelations: we all know what Odysseus does to his wife’s suitors. But does that make them any less real? Indeed, I take this view, but it’s quite arguable to take the opposite view, that this is a play about how false love is, in almost all its forms. (We also have three different types of love in the three men: love of the opposite sex; love of family; love of friendship.) Even the last words uttered in the play, “Love is saved,” have a two-faced meaning: the four men’s failure to win her heart means that the love between Penelope and Odysseus is saved; and yet all of the men’s loves fail and they will be killed because of it.

This is all by means of saying that this play bears incredible intellectual fruit. It is, like Beckett, like Brecht, deep in meaning and rich in metaphor. But, also like Beckett and Brecht, it is incredibly hard to stage successfully. And Steppenwolf falls short. After all, it takes a particular kind of cast, a particular kind of director, a particular kind of talent to pull those playwrights off. It is not enough to simply be a great actor or director. To be sure, Steppenwolf fills the stage with talent: each actor, including Logan Vaughn, who plays Penelope, has proven talent. And Letts’ monologue to Penelope is stunningly delivered. But that’s the only real moment of clarity in the piece. Everything else just doesn’t quite work. The monologues can get boring; the lack of action can get dull; the nothingness does not engage. But I ask you this: how many productions of Endgame or The Wedding have been weird and boring and not engaging? How many have fallen flat on their faces? When Endgame first came to the stage, people didn’t understand what was going on and directors and actors didn’t know how to stage it. There were people in trash cans, for god’s sake. These days, certain companies are known for being able to tackle these kinds of plays, like The Gate Theatre in Dublin, which is easily one of the best (if not the best) place to see Beckett done in the world. So, yes, Steppenwolf failed in this production. Not totally – the design is great, there are some fine ideas at work in the direction and acting, phenomenal talent at work; but they could not breathe life into this play correctly. I know I will be in the minority here, blaming the place and not the play. But I saw an interesting and lively and beautiful play underneath everything. Enda Walsh is a wordsmith, the language he uses is beautiful and exceptionally written. And the play itself, I say again, I find fascinating and highly worthy of both praise and production. But, sadly, this particular one falls short. Perhaps in a few years – maybe with some Irish help – the right people will come together and create magic with this piece.

Somewhat recommended

Will Fink

Reviewed on 12.14.11

For more info checkout the Penelope page at theatreinchicago.com