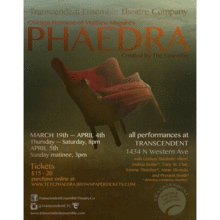

Phaedra

An Ensemble Devised Production

Produced by Transcendent Ensemble Theatre Company

Interesting Exercise in Modernizing Tragic Passion

The story of Phaedra, the Minoan princess who tried to seduce her step-son and then accused him of rape, is not one of the first that springs to mind when most people think of Greek mythology. However, it has drawn the attention of dramatists for thousands of years, from Euripides and Seneca to Sarah Kane. Transcendent Ensemble Theatre Company, a relatively new group, is now performing the Chicago premiere of a contemporary version by Matthew Maguire that seems to draw mainly from Jean Racine’s neo-classical reworking of the characters’ motivations. It’s a production that aims for intensely psychological discomfort, and while I am unconvinced by how Maguire attempted to update the setting, the actors’ dedication elicits ample feelings of alarm, disgust, and fear.

TETC inhabits one of the most unusual performing spaces I’ve seen thus far, and integrates it into their production, though sometimes at the expense of a few sightlines. The long narrow room is painted white instead of the usual black, with a chair rail and night lights, and a wood floor. It does look like the inside of someone’s house (though not a tycoon’s), and puts the audience almost in direct contact with the actors, who often throw themselves at walls and each other. Chairs which nobody at the press opening was bold to take are situated in the middle of the playing space. The labyrinth metaphor doesn’t really come across and isn’t all that relevant in a modernized version, but this staging does create an eerie, voyeuristic atmosphere which feels like a trap.

During the pre-show we are subjected to a looped recording of babies crying. It’s irritating, and we see the two servants, Nonny (Annie Slivinski) and Angus (Preston Smith) wander into the playing space, looking for any reason to no return to the nursery. If you’re close enough to hear the banter, you’ll get some insight into the characters’ relationships, and the status of the household. The rest of the family all make brief appearances: Faye (Lindsay Bartlette Allen), the young second wife and mother of the babies, Thomas (Tony St. Clair), the still virile big shot, William (Joshua Butler), his suffering bastard son who just wants to be a rancher, and Aricia (Emma Thatcher), the daughter of Thomas’s vanquished rival. As we soon see, it’s a family consumed by lust for power channeled into sensuality.

The love triangle at the heart of the story is that William, who has always been cold towards all things sexual and personal, has fallen for Aricia. But Faye is madly in lust for William. In an attempt to avoid shame and self-defilement, she is committing a slow suicide by starvation, but her loyal maid Nonny (whom Slivinski plays with exceptional nuance) won’t allow that, and schemes how to both preserves Faye’s honor and get her what she wants. Meanwhile, Thomas is becoming attracted to Aricia, which she manipulates to her advantage in controlling the company. One day, when Thomas disappears, the lechers make their moves, and disaster follows when he returns. But besides the main entanglements, the characters hit on each other in almost every combination, and only aggravate the self-loathing and confusion.

The play’s biggest strength and weakness is Maguire’s poetry. His references to boardroom maneuvers and the health of a company are clumsy, and “keeping an eye on her” isn’t a good enough reason for Thomas to keep Aricia around, nor do I understand why anyone cares that William’s a bastard. We’re told she’s a financial genius, which is unbelievable, although what Maguire gets right is that the characters who grew up with money have a more natural air of nobility than the grubbing social climbers. He’s at his best when the characters describe their erotic dreams involving animals, which they interpret as symbolic of each other (the original Phaedra’s mother copulated with a bull). Faye in particular comes up with creative metaphors for how consumed she is by lust, though everyone else holds their own. The actors pour every crude passion into these speeches, which reverberate around Transcendent’s claustrophobic space. Along with deceptively simple use of lighting, usually just flipping a switch, the aural element of this play produces the anxiety appropriate for this story. Other scripts have tried for higher tragedy, but this Phaedra excels at horror.

Recommended

Jacob Davis

Reviewed March 18, 2015

For more information, see Phaedra’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing at Transcendent, 1434 N Western Ave, Chicago.