Satchmo at the Waldorf

By Terry Teachout

By Terry Teachout

Directed by Charles Newell

Produced by Court Theatre, Chicago

Louis Armstrong’s Soul on Display without His Musical Armor

“I shit myself,” Louis Armstrong grumbles at the beginning of the play. Yes, he adds, he swears a lot, just not on the Ed Sullivan show. It’s not like he enjoys upsetting his audience. He knows they want to see him as a jovial family entertainer, and there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s just that he’s a product of a dangerous part of New Orleans, has spent his whole life rubbing shoulders with gangsters, and now, at the age of sixty-nine, months away from death, he’s become incontinent. Actually, he muses, the grace period he was given to change his pants is a good opportunity to work on his memoirs. So “Satchmo,” as the famous trumpeter liked to be known, pulls out his tape recorder, and comments on the contradictions in his persona that have plagued him for years. His reflections do not take him to a happy place.

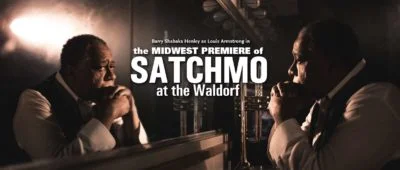

Satchmo at the Waldorf is a one-man play by theatre critic and Louis Armstrong biographer Terry Teachout. For its Chicago premiere, Court helped to create a festival dedicated to Armstrong, which includes exhibits at the Beverly Arts Center, among other events. Armstrong himself is depicted in a heroic performance by Barry Shabaka Henley, who captures the artist’s volatile, extreme emotions, as well as his deceptively knowing cackle. But he also plays two other characters Armstrong is fixated on at the end of his life. One is his late manager, Joe Glaser, a white Jewish man Armstrong trusted, depended on, admired, and now feels has betrayed him from beyond the grave. The other, suave in his shades and blue spill-light, is young upstart Miles Davis—The Accuser—who calls Armstrong a fossil who sold out his talent by becoming an Uncle Tom, and his relationship with Glaser is the proof. Armstrong makes a solid defense for himself, but among the three voices, a complex and fascinating portrait of him emerges.

When Armstrong was a boy, a Jewish family acted as mentors to him, and he wore a Star of David thereafter. He credits his time in a reformatory with teaching him life-skills, and when he was ready to go out into the world, a black gangster told him to find a white boss who would call him “my nigger.” When Armstrong got into trouble with insane Jewish mobster Dutch Schultz, he decided one of Al Capone’s club managers, Joe Glaser, could be that white boss. Glaser’s style was, in his words, to treat Armstrong like a king, and work him like a dog. He bought off Schultz somehow, and for years afterward, he would shepherd Armstrong around the south. Sometimes, when he had the influence and felt like using it, Glaser would put Armstrong in a position to temporarily break barriers by becoming the first black person to play in a certain venue, and be allowed to eat and sleep there. Other times, Armstrong would have to sneak into kitchens through alley-doors to get a meal. Armstrong resented his mistreatment, but it only happened sometimes, or, at least, not all the time, and the money was good.

When Armstrong was a boy, a Jewish family acted as mentors to him, and he wore a Star of David thereafter. He credits his time in a reformatory with teaching him life-skills, and when he was ready to go out into the world, a black gangster told him to find a white boss who would call him “my nigger.” When Armstrong got into trouble with insane Jewish mobster Dutch Schultz, he decided one of Al Capone’s club managers, Joe Glaser, could be that white boss. Glaser’s style was, in his words, to treat Armstrong like a king, and work him like a dog. He bought off Schultz somehow, and for years afterward, he would shepherd Armstrong around the south. Sometimes, when he had the influence and felt like using it, Glaser would put Armstrong in a position to temporarily break barriers by becoming the first black person to play in a certain venue, and be allowed to eat and sleep there. Other times, Armstrong would have to sneak into kitchens through alley-doors to get a meal. Armstrong resented his mistreatment, but it only happened sometimes, or, at least, not all the time, and the money was good.

Another important thing to remember, Glaser tells him, is that most people don’t actually care about the music. It’s the grinning, chuckling, nonsense-noise making Satchmo persona people adore. Well, Armstrong, says, he likes to smile. That doesn’t mean he can’t still cuss out Eisenhower and Arkansas governor Orval Faubus in print when they really deserve it. Even if he gets censored.

Another important thing to remember, Glaser tells him, is that most people don’t actually care about the music. It’s the grinning, chuckling, nonsense-noise making Satchmo persona people adore. Well, Armstrong, says, he likes to smile. That doesn’t mean he can’t still cuss out Eisenhower and Arkansas governor Orval Faubus in print when they really deserve it. Even if he gets censored.

Perhaps Glaser’s belief that Armstrong’s music wasn’t actually key to his popularity among white audiences is the dramaturgical reason for why we don’t hear much of it during the show. Some audience members may be surprised by that, and Armstrong certainly insists that his horn is an extension of himself. But when “Hello, Dolly,” a song Armstrong found unmemorable, becomes his greatest hit late in his career, he has to consider that maybe a lot of his fans really don’t get him. He’s not blind to how few black people are attending his performances by the end, and goddammit, it’s pronounced “Lewis.” John Culbert’s scenic design casts Henley adrift on a square wooden island, where he often catches sight of himself in a massive mirror along the back wall. It’s the perfect place for reflection, and for confronting the divide between audience and actor. I cannot stress enough how powerful Henley’s performance is. Near the end, when Armstrong details how he believes Glaser truly never reciprocated his respect, his pain and self-rebuke is strong enough to make the audience wince.

A note from Teachout explains which parts of the play are real, and which fictional. His explanation makes the end a tragedy for both Armstrong and Glaser, who did indeed care for his friend, but had his own flaws and pressures. Teachout and director Charles Newell were quite excited about this project, and the result is an astonishing examination of how the compromises an artist makes take a toll on him psychologically. It’s not only educational, it’s riveting. Deep down, Armstrong says, jazz is happy. Never mind what’s on his pants.

A note from Teachout explains which parts of the play are real, and which fictional. His explanation makes the end a tragedy for both Armstrong and Glaser, who did indeed care for his friend, but had his own flaws and pressures. Teachout and director Charles Newell were quite excited about this project, and the result is an astonishing examination of how the compromises an artist makes take a toll on him psychologically. It’s not only educational, it’s riveting. Deep down, Armstrong says, jazz is happy. Never mind what’s on his pants.

Highly Recommended

Jacob Davis

This show has been Jeff recommended.

Playing at Court Theatre, 5535 S Ellis Ave, Chicago. Tickets are $45-65; to order, call 773-753-4472 or visit CourtTheatre.org. Playing Wednesdays and Thursdays at 7:30 pm, Fridays at 8:00 pm, Saturdays at 3:00 pm and 8:00 pm, and Sundays at 2:30 and 7:30 pm through February 7. Running time is ninety minutes with no intermission.