The Firestorm

By Meredith Friedman

Directed by Drew Martin

Produced by Stage Left Theatre

Playing at Theater Wit, Chicago

Racial Incident is Unfinished Business

In the age of the internet, a college kid who gets arrested at a student union for drunkenly shoving and yelling homophobic slurs at a cafeteria worker for denying him mac and cheese will be subject to a lifetime of embarrassment. (Maybe. Nobody really knows, yet.) However, at least it’s not a secret hanging over his head that could suddenly ruin him at any time, were it to be discovered. In Meredith Friedman’s new play The Firestorm, which Stage Left Theatre is presenting as part of a National New Play Network rolling world premiere, the author examines what happens when a long-kept secret of something that is terrible, but anomalous, in a politician’s past suddenly emerges. It’s an interesting idea for a play, and Friedman builds some good scenes from it. But it still feels underwritten, and Drew Martin’s direction drags out the play’s weakest moments.

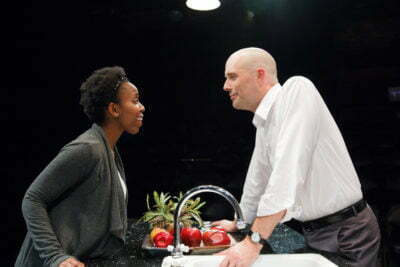

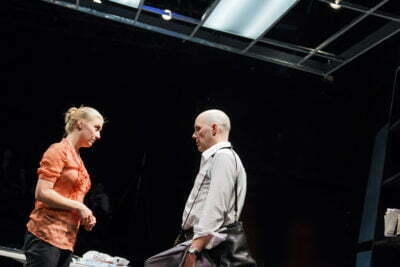

Patrick Henderson (Vance Smith) is running for governor of Ohio, and is maintaining a narrow lead in the polls. As part of building his image as a former blue collar kid from the South who wants to help others like himself through progressive policies, his publicist, Leslie (Melanie Derleth) wants to coach his wife, Gaby (Kanomé Jones), in how to appeal to traditional, mainstream voters. Meaning, Gaby is black, a corporate lawyer, irreligious, uninterested in being a mother, and from a wealthy background, and Leslie sees that as less than ideal. But Patrick depends on Gaby, not only for outreach among black voters, but for all of his major decisions, and quite a few of his minor ones. The two have been married for less than a year, but are deeply in love with each other. Although, there are a few tensions owing to the difference in their backgrounds, which they haven’t quite worked out yet.

Soon, they have a much bigger problem. One of Patrick’s subordinates unknowingly rejected a man with incriminating evidence against Patrick for a campaign position, and as revenge, the man leaks what he knows to the media. When he and Patrick were freshman at university, they pledged a fraternity, and as part of their initiation, they were ordered to scrawl “Go home, n—ˮ on a black student’s door. They did, and Patrick quit the fraternity the next day, but he emailed his accomplice about it years later. Patrick comes clean to his staff, but far worse is having to confess to Gaby. She takes it surprisingly well, and is willing to stick by him. But still, the question remains: what are they to do? The Washington Post has an interview with the black former student, Jamal (David Lawrence Hamilton) scheduled, and what Patrick would really like would be for this whole problem to just go away.

The cast acquits themselves well when the script gives them something to work with. When Jamal finally gets to tell his story, Hamilton delivers it in a quiet, but riveting monologue. Smith avoids taking Patrick down the path of a histrionic meltdown; instead, he becomes more frazzled until he begins talking of having kids once “things have settled down,” implying he has resigned himself to losing, and is only trying to weather the blows to his reputation as best he can. As Gaby, Jones makes clear that she is used to being bored with people, and unaccustomed and unwilling to dumb herself down. And yet, her yearning for both love and reflected glory forces her to compromise constantly, making her tense and always able to instantly snap into her professional mode. She, too, delivers a devastating monologue, once she opens up emotionally for the first and last time.

The problem is that Gaby’s monologue comes out of nowhere. It’s possible that she was suppressing her initial emotions, or uncertain of them, and it took something innocuous to set her off. But since so much of the play is made up of drawn-out scenes from her and Patrick’s marriage as they discuss upper-middle class inanities and debate race light-heartedly through the lens of celebrity gossip, the sequence of events comes across as poorly structured. The revelation of Patrick’s past misdeed seems like the first interesting thing that has ever happened to them. I also get very little sense of what Patrick has been doing for the past twenty years (Doom, which he played in college, came out in 1993). It was mentioned that he had some kind of local government supervisory job in Columbus, but he seems to have no black contacts besides his wife, and his evidence for being the best candidate for black people is to rattle off a few talking points about sentencing reform and bailing out homeowners. With so little to contextualize his past or current actions, the questions Friedman raises about penance and growth are still too vague to be compelling. There are some good moments here and a strong plot outline, but at such a short length, more character development could have only helped The Firestorm.

Somewhat Recommended

Jacob Davis

[email protected]

Reviewed November 6, 2015

For more information, see The Firestorm’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing at Theater Wit, 1229 W Belmont Ave, Chicago. Tickets are $20-30; to order, call 773-975-8150 and see stagelefttheatre.com. Performances are Thursdays through Saturdays at 8:00 pm and Sundays at 3:00 pm through November 29. Running time is ninety minutes with no intermission.