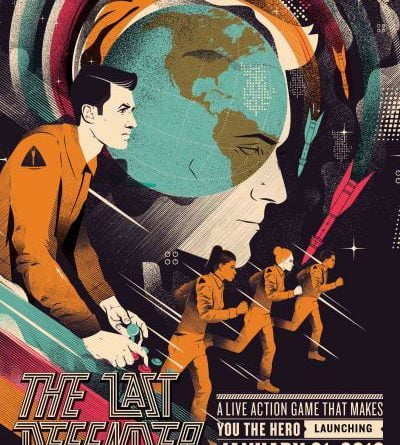

The Last Defender

Written and Directed by Nathan Allen

Puzzles by Sandor Weisz

Artistic Direction by Chris Burnham

Produced by The House Theatre of Chicago

Theatre Company Destroys Chicago

18:30: I arrive early to the downstairs Chopin to take over my task as last defender of the world. The command center is still being re-set from the previous last defenders’ shift. I am issued my identification card, and page through my program of Nabucco while awaiting the arrival of the rest of my team-mates. I am in the communications division.

19:00: Orientation begins. Our task is to monitor Soviet nuclear activities, and to save the world, destroy it, or reach some kind of compromise. We are told that saving the world is the most difficult outcome to achieve. Assisting us in solving puzzles will be silent crew members in black bunny masks, and one in a black bear mask. Teamwork will be crucial, so we are reminded to share information, and defer to those who display natural leadership. Tight lips sink ships.

19:05: We enter the locker-room to change into our jumpsuits. The lockers have combination locks. In our first exercise in teamwork, we share our recollections of facing this problem in school, and succeed, after some struggle, in opening our lockers. Within are our jumpsuits (we supplied our sizes in an emailed form ahead of time), belts, and quarters for operating our work consoles. Our defender names are written on our uniforms. I am Defender Countdown. The other member of the communications division also returned his guest ticket, so there were only two of us. I think he was called Defender Strikethrough. Normally there are sixteen team members, but we were down two.

19:10: We take an elevator to our deep underground base. Within is a warning that Zelda, the artificial intelligence in charge of managing the nuclear missiles, tends to malfunction a lot and supply dubious wisdom. There is a key for accessing the nuclear override interface, which we entrust to Defender Strikethrough, thinking him the most competent.

19:20: Inside the main base, we view a tutorial video instructing us on the tenets of Mutually Assured Destruction. Our job is to stay wary in case the Soviets launch missiles at us. If Zelda informs us they have, we are to contact Central Systems Command to verify the threat. If verified, we are to allow the counterstrike to launch automatically. If not, we will have to override the return strike. We are also presented with our orders of the day. I am tasked with going to the library in the corner, and examining the encyclopedia.

19:30: I determine that the encyclopedia is a collection of video cassettes with names of people and cities on them. I assume this will be important to determining a pattern-puzzle later. While I examine the cassettes, an alarm goes off, telling us that the Soviets have launched their missiles. A sixty minute timer appears on the main screen, telling us we have until it runs out before Zelda launches the counterstrike. The ghost bunnies usher us to our consoles so we can attempt to reach Central Systems Command. Our first task is to figure out which city Central Systems Command is located in.

19:35: Defender Strikethrough and I share ideas and information about how to reach Washington. Tight lips sink ships. One of the ghost bunnies points out that while we have been sharing ideas, we neglected to read the instructions directly in front of us. We contact Washington, and find that the phone menu has been encoded. While we work on decoding the phone menu so we can tell whether or not we are under attack, Zelda lists American cities that have been wiped out, at the rate of one about every ten seconds.

19:39: We reach Central Systems Command and are put on hold.

19:40: We ascertain that the purported Soviet strike is a computer error. The ghost bunnies guide us through figuring out how to access the override module. It involves spelling out “denuclearization” with only a sign with the word “denuclearization” written on it to guide us.

19:50: We succeed in spelling “denuclearization” despite the absence of two team-mates, and access the override console. There are ten missiles in the Chicago base which will launch in forty minutes, and we have to disable each one individually by plugging in certain letter-number combinations. To obtain these combinations, we have to solve the puzzles throughout the room. Delegation is required. Some team members who happen to be professional actors step into the role of leadership, and dispatch us to stations. I have noticed that often when a group of people are confused and irresolute, actors will take charge. I think this is because they are able to project their voices and are accustomed to making strong character choices. As a critic, I was concerned that we had not given sufficient debate to whether we wished to prevent a nuclear war or cause one, but I am less accustomed to being inspirational or co-operative.

20:00: A ghost-bunny holds my hand while I attempt to figure out the secret of the cassettes. Following our ghost-bunnies’ non-verbal urging to provide help to others, nobody actually ends up at the station they were delegated. Instead, we flit around, solving parts of mind puzzles, or attempting to figure out what the puzzles are. There are ones involving weights, the game battleship, the cassettes, dots on pillars, laser dots, and bunkbeds, among other things. I end up with a box which, by its label, contains a tactile puzzle. I sit despondent and perplexed, sifting through the box’s contents until a ghost-bunny takes pity on me, and brings over help.

20:00: A ghost-bunny holds my hand while I attempt to figure out the secret of the cassettes. Following our ghost-bunnies’ non-verbal urging to provide help to others, nobody actually ends up at the station they were delegated. Instead, we flit around, solving parts of mind puzzles, or attempting to figure out what the puzzles are. There are ones involving weights, the game battleship, the cassettes, dots on pillars, laser dots, and bunkbeds, among other things. I end up with a box which, by its label, contains a tactile puzzle. I sit despondent and perplexed, sifting through the box’s contents until a ghost-bunny takes pity on me, and brings over help.

20:10: My team-mates find an instructional manual in the box, which I somehow overlooked. I resign the tactile challenge, and join the group working on the cassettes to “help.”

20:15: I join the group working on electrical paths and “help.”

20: 20: I join the group working on dots and “help.”

20:25: The group working on the tactile puzzle realize that they need my help to identify chess pieces and set up the game board. Using my unique skill set, we are able to complete the puzzle, obtain the code, and disable a missile. Each of us feels like a valued member of the team, and that we have gained insights into co-operation and communication. The ghost-bunnies are proud of us.

20:29: With less than a minute to go, nobody has any idea how to solve the last puzzle. One of our leaders decides we should blow ourselves and the Chicago area up to disable the last missile, and those of us nearby meekly hand over our key cards in deference to the loud voice. We also collect key cards from the team-members who were distracted and don’t know what they are agreeing to, but understand we need their cards for something important. I feel that we have gained insight into how mass suicides happen. The ghost-bunnies brace for impact.

20:30: The world is saved, at the cost of Chicago. Following the conclusion of the game, we are told the secret of the final puzzle, and I still don’t understand it. Apparently, it is very rare for anybody to succeed in obtaining peace without casualties. Our team came the closest one can to achieving the best outcome without actually achieving it. We are invited back to play the game again.

Certainly, there was a huge amount I didn’t see. There were some puzzles I didn’t touch at all, and some I wasn’t even aware of because I mostly kept to one side of the room. On the other hand, it is possible for a person who already knows how most puzzles and the override console work to push their way through without sticking to the script. That might not be a bad thing; given the interactive nature of this kind of story-telling, more of a role-playing element would have been welcome. New players are likely to spend much of the ninety minutes too confused to do anything but what they are told.

Certainly, there was a huge amount I didn’t see. There were some puzzles I didn’t touch at all, and some I wasn’t even aware of because I mostly kept to one side of the room. On the other hand, it is possible for a person who already knows how most puzzles and the override console work to push their way through without sticking to the script. That might not be a bad thing; given the interactive nature of this kind of story-telling, more of a role-playing element would have been welcome. New players are likely to spend much of the ninety minutes too confused to do anything but what they are told.

Those who were most active in taking command and matching the game’s rapid pace seemed to have had the most fun, and nostalgia for eighties titles like War Games seemed to help a lot, too. The only one of Sandor Weisz’s puzzles I saw through from start to finish looks ridiculously easy in retrospect, and the difficulty was created mostly by the chaotic environment of the room. But it may have been unique in that regard, or maybe that’s just the nature of mind puzzles. As usual for the House, the event has incredibly cool aesthetics. This game is definitely a must-play for puzzle nerds, and is worth checking out for anyone whose interest is piqued by the premise.

Recommended

Jacob Davis

[email protected]

Reviewed January 31, 2016

For more information, see The Last Defender’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing in the downstairs at the Chopin theatre, 1543 W Division St, Chicago. Tickets are $40-45 with discounted student, industry, and same-day tickets available. To order, call 773-769-3832 or visit thehousetheatre.com. Playing Thursdays at 7:00 pm, Fridays at 7:00 and 9:00 pm, Saturdays at 2:00, 4:00, 7:00, and 9:00 pm, and Sundays at 4:30 and 7:00 pm through March 13. Running time is ninety minutes.