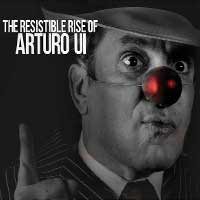

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui

By Bertolt Brecht.

Translated by George Tabori and Alistair Beaton.

Directed by Victor Quezada-Perez.

Produced by Trap Door Theatre, Chicago.

The Irresistible Rise: Brecht for the 21st Century Dupe?

Written in 1941, Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui was, in his own words, conceived as a “parable play, written with the aim of destroying the dangerous respect commonly felt for great killers;”1 and, as the title and Brecht’s philosophy suggest, it is a parable whose “moral” may well be interpreted as vigilant resistance on the part of the people. In 1941, the rise of Ui, a monomaniacal Chicago gangster bent on wresting control of the produce market, was a parody of Hitler and the Nazis rise to power: today, any circumspective theater-goer may easily discern the relevance of Trap Door’s production.

Yet, if it was difficult for Moshe the Beadle to convince his fellow Jews of what he saw in his exile with the other foreigners, one should be wary of assuming the rise of fascism is any easier to discern in our day. The pattern of history lies only in our eyes—and to them. In what some term the post-truth politics of our day, French Director Quezada-Perez translates Brecht’s parodic parable into a full-blown farce; and while this style seems somehow appropriate for our present circumstances, the farcical absurdity nonetheless confounds one’s sense of the atrocity transpiring beneath it. Once again in the words of Brecht on his play: “pure parody however must be avoided, and the comic element must not preclude the horror.”1 In this production (as in the past events to which it references) the horror hits us as an afterthought—realized only after two solid hours of unadulterated shtick.

Arturo Ui (Antonio Brunetti) is a two-bit gangster whose childishly simple (and frighteningly so) desire is to be recognized as great. His opportunity finally comes when he catches whiff that Dogsborough (Bob Wilson), a politician of high reputation for being honest, has mired himself in a corrupt business scheme. You see, the Cauliflower Trust, the collective of produce businesses in the area, have hit hard financial times, and, unable to get Dogsborough to support them with a loan through the city, they have sold him the majority shares of the trust, thereby making their problem his problem. Capitalist principles at work, Dogsborough ends up pushing the loan through to save the Trust.

Without a respectable leg to stand on, Dogsborough thus gives in to Ui’s blackmail and gives him a position of power. Now that they’re politically protected, Ui and his henchmen start hitting up the grocers for “insurance” (you might say) against any unforeseeable, unfortunate unpleasantness.

With his power in Chicago assured, Ui next turns his eyes toward Cicero and control over its produce market. The only impediment there is Dullfoot (also Bob Wilson) and his newspapers that decry Ui as a violent gangster. In order to distance himself from the allegations, Ui betrays his right-hand man Roma (Casey Chapman) and has him killed for his ties to the gang activity in Chicago. Ui is haunted by the ghost of Roma, who predicts Ui’s own demise by similar means (of betrayal); yet Ui is ultimately triumphant, as, in the last scene, he diplomatically threatens the workers of Chicago and Cicero with violence if they do not accept him wholeheartedly—and they do, with all their hands raised in subjected fear.

There is much more to this production than this simple synopsis offers. For one, there are the delightful, multi-character performances by most in the cast—especially Nora Ulrey who plays no less than four characters and who practically steals the stage with each one. Then there is the music that intermittently scores the production: muted horns whine out with their muffled voices; the Barker/Announcer (David Steiger) tickles the keys of an electric piano, somberly playing Chopin’s Funeral March during a real mock trial, then tarting it up with a Bossa Nova rhythm; and, later, ironically scoring Ui’s nightmare dream of Roma’s ghost with Liszt’s Liebestraum (?)—which scene puts stage-smoke and an unearthly green light to effective use in one of the most striking framings I’ve ever seen in a Chicago blackbox production.

Most noticeable of the effects in the production, however, are the red clown noses that adorn every character. These are, at once, richly and effectively symbolic, and symptomatic of the unrelenting comedic style that robs the production of its underlying “horror.” The world to which these red noses introduce us is one in which everyone is, to some conscious degree, implicated in the corruption. When a character dies, his or her red nose is torn from their face and they are (as I interpret it) forced to breathe the noxious, corrupt, “fishy” odor that pervades this world—a reality they had denied; indeed, it may be assumed that it is of this that they finally die. In the production’s most poignant moment, Ui and his henchmen remove their red noses and their caricature-esque gestures fall away to reveal the real, dimensional criminals that they are. This moment has a visceral quality to it, as if one awoke from a circus dream to find it were only a gaudy gild on a harrowing reality.

Yet though this moment is well earned, it came too late for me. The parade of outlandish antics and comedy, far from engaging me in the dialogue of Brecht’s play, lulled me into a state of disorientation: halfway through I no longer knew what I was watching, and why it hadn’t ended yet; I neither cared nor did not care: I was apathetic. And so I asked, Why is that?

One possible answer is that The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui did not feel so resistible. In fact, it felt irresistible and therefore futile. Director Quezada-Perez’s world of red noses has everyone cast as dupes to the master dupe. From the supposedly honest Dogsborough, to the petit-bourgeois, to mister and missus Dullfoot, and even the proletariat workers. Under their red noses and their grand gestures, these characters do not exhibit even a potential of resistance; rather, their “gesture” is Ui’s own: they already seemed corrupted, and his corruption is irresistible to their dupe world. In other words, what is lost in this production is that the people had an opportunity to resist and that their failure was in not taking Ui’s violence seriously and withstanding it. In fewer words: they are already shown to be complicit and so the insidious horror of their gradual complicity is absent.

While this may actually be Director Quezada-Perez’s point in his staging of The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, and while it is a point well worth timely meditation, it might well have found a less obstructive expression, as it seemed to me to fight against the drama of the play. Fans of Trap Door (of which I count myself one), may find this production in line with their previous offerings: it is sophisticated, and it is quirky. But the quirkiness plays out as a two-hour long joke, and the punch line, though sophisticated and somewhat satisfying, comes only too late.

Somewhat Recommended.

August Lysy.

Reviewed on 16 March 2017.

Playing at Trap Door Theatre, 1655 W Cortland Ave., Chicago. Tickets are $20-$25. For tickets and information, call the Trap Door box office at 773-384-0494, or visit TrapDoorTheatre.com. Performances are Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays at 8:00 p.m. through April 22nd. Running time is 2 hours with no intermission.

1 Brecht, Bertolt. The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui. Trans. John Willett. Eds. John Willett, and Ralph Manheim. London: Methuen Drama, 2007.