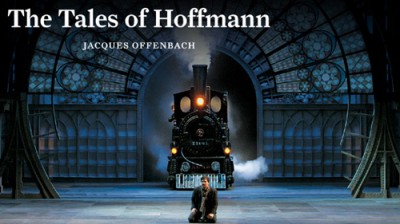

The Tales of Hoffmann

Composed by Jacques Offenbach

Libretto by Jules Barbier

Based on stories by E. T. A. Hoffmann

Directed by Stéphane Roche

Conducted by Emmanuel Villaume

At the Lyric Opera, Chicago

The Eternal-Feminine draws us onward.

Unsurprisingly, the Lyric has done it again. They have created a truly enjoyable (if wholly traditional) production of a great (and very eccentric) opera. Les Contes D’Hoffmann is widely considered Jacques Offenbach’s masterpiece; and, like Mozart’s (the Mass in C minor), he left it unfinished at his death. It is based on a play by Jules Barbier, who also wrote the libretto, and Michel Carré, which is in turn based on short stories written by E. T. A. Hoffmann himself (he of the title). Offenbach decided this would be the perfect vehicle for his as-yet-unwritten “great opera,” the piece that would ensure the carriage of his name through the ages. It is unnecessary to say, but it worked.

Hoffmann (tenor Matthew Polenzani) is a lovelorn, hopeless poet inspired by the Muse of Poetry (Emily Fons), losing his loves to Evil, always played by the same man (bass/baritone James Morris). Really, Hoffmann says, though he relates three tales of love through the opera, it is the story of one girl, the prima donna Stella (Emily Birsan); but it is three different aspects of his love for her: the naïve, early love; the love of her as an artist; and the lust for her beauty. Each time Hoffmann is thwarted by the same evil force, again presented as different aspects of the same power. The piece opens at a tavern next to the opera house where Stella is performing. Hoffmann and his best friend Nicklausse (who is also the Muse of Poetry) enter and entertain the patrons with a song; but Hoffmann wanders into fancy, talking of his love. Councillor Lindorf (the incarnation of evil in the story frame) convinces Hoffmann to regale the crowd with the stories of his three loves.

Hoffmann (tenor Matthew Polenzani) is a lovelorn, hopeless poet inspired by the Muse of Poetry (Emily Fons), losing his loves to Evil, always played by the same man (bass/baritone James Morris). Really, Hoffmann says, though he relates three tales of love through the opera, it is the story of one girl, the prima donna Stella (Emily Birsan); but it is three different aspects of his love for her: the naïve, early love; the love of her as an artist; and the lust for her beauty. Each time Hoffmann is thwarted by the same evil force, again presented as different aspects of the same power. The piece opens at a tavern next to the opera house where Stella is performing. Hoffmann and his best friend Nicklausse (who is also the Muse of Poetry) enter and entertain the patrons with a song; but Hoffmann wanders into fancy, talking of his love. Councillor Lindorf (the incarnation of evil in the story frame) convinces Hoffmann to regale the crowd with the stories of his three loves.

The first is an automaton (Anna Christy) created by a scientist, Spalanzani (David Cangelosi), and his companion, the evil Coppélius. Hoffmann is clueless as to the girl’s reality, and only becomes aware of what a joke his love is when Coppélius destroys her in the end. The second love is the singer Antonia (Erin Wall), who has been blessed with an exceptional voice, but cursed with an affliction that grows worse when she sings. Her father has taken her away from Hoffmann, who encourages her musical career, thus unwittingly endangering her. However, when Dr. Miracle (this story’s incarnation of evil) arrives, he tricks Antonia into singing, thus killing her. Lastly, we meet the beautiful courtesan Giulietta (Alyson Cambridge), whose love for material wealth causes her to fall under the spell of the magician Dapertutto, who wants Hoffmann’s reflection. She snatches it from him, and runs off with another man, leaving Hoffmann desolate. At which point we rejoin Hoffmann and the revelers in the tavern.

The first is an automaton (Anna Christy) created by a scientist, Spalanzani (David Cangelosi), and his companion, the evil Coppélius. Hoffmann is clueless as to the girl’s reality, and only becomes aware of what a joke his love is when Coppélius destroys her in the end. The second love is the singer Antonia (Erin Wall), who has been blessed with an exceptional voice, but cursed with an affliction that grows worse when she sings. Her father has taken her away from Hoffmann, who encourages her musical career, thus unwittingly endangering her. However, when Dr. Miracle (this story’s incarnation of evil) arrives, he tricks Antonia into singing, thus killing her. Lastly, we meet the beautiful courtesan Giulietta (Alyson Cambridge), whose love for material wealth causes her to fall under the spell of the magician Dapertutto, who wants Hoffmann’s reflection. She snatches it from him, and runs off with another man, leaving Hoffmann desolate. At which point we rejoin Hoffmann and the revelers in the tavern.

That is a facile rundown of the story; there are myriad subtleties, clever jokes, songs which bring laughter and sadness, which plumb the depths of despair and flutter in the heights of love and wonder. The score is beautiful. And so well-crafted! Offenbach is in complete control, making each song affect exactly how he wants it to. There is the comic chanson about the dwarf Kleinzach, Il était une fois à la cour d’Eisenach, which is a light-hearted, call-and-respond affair until Hoffmann becomes distracted by a daydream of his love Stella, at which point the demeanor of the song is transformed into a beautiful, soaring, romantic thing. It is because of this that Hoffmann is pressured into telling the tales of his previous loves. There is also the ridiculous couplets by the servant Frantz (Rodell Rosel), Jour et nuit, in which a man sings to us that he is no good at singing. Indeed, the second act is something like a comedy masquerading as a tragedy: after all, it is absurd on its face, the idea that, in an opera, one has vowed not to sing. The story is sad – Antonia is ultimately killed by her desire to be a great artist – but Offenbach always throws in elements of the absurd.

That is a facile rundown of the story; there are myriad subtleties, clever jokes, songs which bring laughter and sadness, which plumb the depths of despair and flutter in the heights of love and wonder. The score is beautiful. And so well-crafted! Offenbach is in complete control, making each song affect exactly how he wants it to. There is the comic chanson about the dwarf Kleinzach, Il était une fois à la cour d’Eisenach, which is a light-hearted, call-and-respond affair until Hoffmann becomes distracted by a daydream of his love Stella, at which point the demeanor of the song is transformed into a beautiful, soaring, romantic thing. It is because of this that Hoffmann is pressured into telling the tales of his previous loves. There is also the ridiculous couplets by the servant Frantz (Rodell Rosel), Jour et nuit, in which a man sings to us that he is no good at singing. Indeed, the second act is something like a comedy masquerading as a tragedy: after all, it is absurd on its face, the idea that, in an opera, one has vowed not to sing. The story is sad – Antonia is ultimately killed by her desire to be a great artist – but Offenbach always throws in elements of the absurd.

And yet, although the overall effect of The Tales of Hoffmann is comic, Offenbach is a deft manipulator of emotions, and the very end of the piece is profoundly and deeply affecting. At the very end, Offenbach brings true, devastating weight to the opera, and leaves the audience with exactly the feeling he wishes.

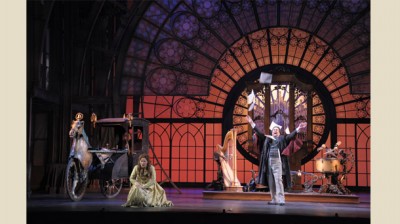

And the production at the Lyric is beautiful. The sets are properly grandiose for opera, at once simple, expansive, and intricate; in a word, brilliant. The costumes are impeccable, the lighting design really excellent. All of the performers are marvelous, the pit is spot-on. It’s simply a wonderful experience.

Highly recommended

Will Fink

Reviewed on 10.5.11

For full show information, visit TheatreInChicago.

At the Lyric Opera, 20 N. Wacker Drive, Chicago, IL; call 312-332-2244, www.lyricopera.org; tickets $33-$194, through October 29, 2011. Running time is 3 ½ hours.

Every weekend i used to visit this site, as i wish for enjoyment, as this this

web site conations genuinely fastidious funny material too.