Tug of War: Foreign Fire

By William Shakespeare

Directed by Barbara Gaines

Produced by Chicago Shakespeare Theater

Shakespeare’s Mythmaking Comes to Life

Historical narratives, no matter how distant, contain something universal. William Shakespeare was writing during an early awakening of English nationalism, when, having finally been severed from France politically and having a ruling dynasty that spoke and encouraged the use of the English language, and with history a rapidly growing field of study, people were interested in learning the truth of their country’s past. His and his contemporaries’ plays about England’s medieval monarchs contained some of the most memorable scenes written for the stage, but, even more so than with other works of the time, finding their contemporary significance is a challenge and the draw for modern artists. Doing so remains a fruitful endeavor; Shakespeare festivals often include productions of his two fourteenth century tetralogies. But for the Chicago Shakespeare 400 Festival, Chicago Shakespeare artistic director Barbara Gaines is doing something very different. This spring’s six-hour long Tug of War: Foreign Fire is made up of the rarely-seen Edward III, Henry V, and Henry VI Part One. Next fall’s accompanying epic, Civil Strife, will consist of the other two parts of Henry VI, and Richard III. It’s an unusual combination, which massively re-contextualizes the Hundred Years War into an examination of personalities, and perhaps most significantly, transforms Henry V into a tragedy. The result, though in some way massive in scale, is also deeply intimate, and through the outstanding work of Gaines, her ensemble, and her production team, a long-ago conflict becomes vital again.

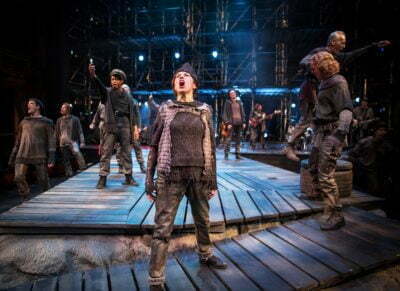

The play is split into four parts, with the first dedicated to a portion of Edward III. However, the opening lines are the famous “O for a muse of fire” prologue from Henry V, during which the nineteen performers put on their paper crowns, and caper around a golden tire swing which represents royal dignity. The play is not limited to any particular time period, since it’s the fictional versions of the characters we’re concerned with, not ever-shifting historical perception. For example, the titular King Edward (Freddie Stevenson, in an outstanding Chicago debut), is a lustful brute who is driven to rage when he is informed that the king of France demands his vassalage. Edward believes that the French throne should have passed to him through his mother, but before making war on the usurping Valois dynasty, he has a Scottish problem to deal with. In Scotland, he is enamored of the Countess of Salisbury (Karen Aldridge, supplying depth to a stock role), and commands her father to seduce her for him. Had this likely collaboration between Shakespeare and Thomas Kyd been written a few years later, his actions would have made Edward the target of a revenge tragedy, but after shocking even himself with his wickedness, he is convinced to wage war on France instead of the women of his own court, and departs with his son, bravely leaving his pregnant wife to defend against the Scots.

The play is split into four parts, with the first dedicated to a portion of Edward III. However, the opening lines are the famous “O for a muse of fire” prologue from Henry V, during which the nineteen performers put on their paper crowns, and caper around a golden tire swing which represents royal dignity. The play is not limited to any particular time period, since it’s the fictional versions of the characters we’re concerned with, not ever-shifting historical perception. For example, the titular King Edward (Freddie Stevenson, in an outstanding Chicago debut), is a lustful brute who is driven to rage when he is informed that the king of France demands his vassalage. Edward believes that the French throne should have passed to him through his mother, but before making war on the usurping Valois dynasty, he has a Scottish problem to deal with. In Scotland, he is enamored of the Countess of Salisbury (Karen Aldridge, supplying depth to a stock role), and commands her father to seduce her for him. Had this likely collaboration between Shakespeare and Thomas Kyd been written a few years later, his actions would have made Edward the target of a revenge tragedy, but after shocking even himself with his wickedness, he is convinced to wage war on France instead of the women of his own court, and departs with his son, bravely leaving his pregnant wife to defend against the Scots.

Gaines’s decision to include Edward III in this lineup was the boldest and most curious decision of the production, since the play is a very early work and only tentatively associated with Shakespeare. Her reason for doing so becomes apparent gradually, as the war gets underway. Stevenson’s Edward is not only a tyrant who only occasionally experiences flashes of humanity, but is also cunning manipulator who speaks in lilting sarcasm and grandiosity. When Stevenson stands with one arm folded, he looks like Edward’s distant descendent Richard III. The second half of the play is largely about how, out of a misguided desire to live up to his father’s expectations, Edward’s son, called Ned (Dominique Worsley), became the Black Prince. Worsley comes across as a reasonable, decent fellow, but Edward states many times that his son’s terrible assignments in battle and afterwards are meant to harden him into a powerful weapon, and that the boy’s life is only as valuable as his skill in combat. The prince wins a major victory, only to be subsequently captured. While he languishes, his father embarks on easier fights. Upon his release, he takes terrible revenge. The two wind up cutting a bloody swath through France, but it is all for nothing, as the heir predeceases the father. Edward had other sons, however, and his psychological programming reverberates down the generations, as he and his son take their place high above the stage to see who will next take up their cause.

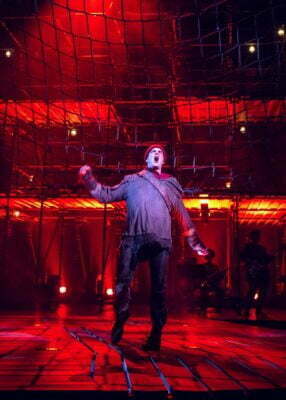

Henry V is the most dramatically and poetically mature play Gaines has chosen to work with, and it contains the emotional core of the play, as well as the most obvious examples of her attempts to prominently feature the stories of the common soldiers. She and costume designer Susan E. Mickey dressed the English noblemen in red robes and the French in teal, with the robes of the monarchs bearing pictures of their own faces. But while Edward always wears his regalia, Henry V (John Tufts) sheds it in battle and while seeking out his men’s honest opinions in disguise. And while battles are referenced, and the kings often comment on them while standing in the metal scaffolding at back (set design by Scott Davis), only combat involving women is actually performed. This shakes us out the conventional way of telling Shakespeare’s histories, and Henry V in particular, so that we pay more attention to the effects of the battles on observers and their aftermath.

Indeed, that Henry actually participates in battles that put him in danger clearly marks him as different from his great-grandfather. It’s not that they’re total opposites; Henry, too, launches war mainly to soothe his wounded ego, is quick to anger, and excels in verbal intimidation tactics. But Henry grows much more of a conscience. After hearing Edward’s voice in his own while threatening French civilians, Henry collapses in exhaustion and shock. Though his teenage years from Henry IV are not depicted, it’s clear that something is preventing him from dismissing the humanity of the commoners on both sides, and learning that they serve him more out of fear than love devastates him. Tufts magnificently handles his character’s not-always-lineal progression as he loses faith in the righteousness of his cause, until his “Upon the king” speech is just a string of desperate, confused self-justifications. The Saint Crispin’s Day speech is powerful and stirring in this version, but its impact comes from Henry’s determination to make something good come of the mess he’s helped create. Heidi Kettenring plays the French princess Katherine, and under Gaines’s direction, the romantic encounter between her and Henry post-Agincourt actually makes sense and isn’t icky. The blame for what happened can’t all be laid on the English, but the two of them hope they’ve found a way to bring peace. If not for their early deaths, they might have.

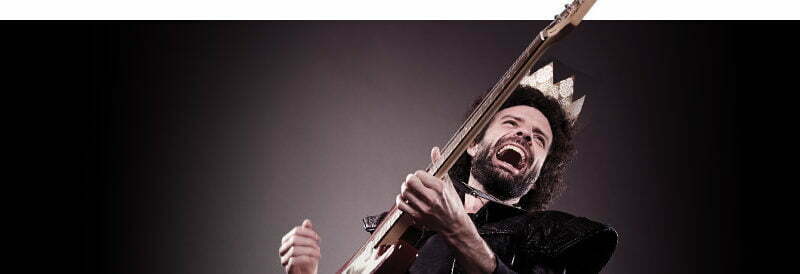

Even with the fascinating comparison and contrast between the monarchs, the speeches and politics could have been very dry had Gaines and her designers not milked as much theatricality as was possible within their concept. Sometimes, they had to go outside the text. A four-person orchestra (Matt Deitchman, Jed Feder, Shanna Jones, and Tahirah Whittington), made up of drums, electric bass guitars, and a cello, plays songs ranging from “Lilac Wine” to Pink’s “So What” and “When Johnny Comes Marching Home,” along with many 60s and 70s anti-war anthems by the likes of Leonard Cohen and Nina Simone. The actors sing all with of them with a British rock sensibility which, besides showing off their fine voices, is what provides the commoners with their most input outside of Henry V. Lindsay Jones’s original music and Anthony Pearson’s lighting are also a big help as far as mood goes, and in Henry VI Part One, they get the greatest mileage for their effects, as the mystical Joan la Pucelle (Kettenring) takes the stage, also allowing for more female-centric combat.

Henry VI (Steven Sutcliffe) could not be less like the previous English kings. He doesn’t have a mean bone in him, and when he learns that one of his uncles has defected, instead of being angry or worrying over the political implications, he’s just hurt and sad. Because Henry VI came to the throne at less than a year old, an entrenched group of nobles wield the actual power and squabble with each other constantly, while he tries to keep the peace. The Lord Protector, Humphrey (Michael Aaron Lindner) exercises restraint to spare his boyish king’s feelings, but in the face of the resurgent French, the nobles literally cannot cooperate to save their lives. David Darlow’s twisted Bishop of Winchester is happy to screw over the empire to advance his international ambitions, Larry Yando’s Duke of York (Richard III’s father in every way) is spiteful and cruel, and Henry is too star-struck by Lord Talbot (James Newcomb) to manage him effectively. Meanwhile, French king Charles VII (Stevenson) demonstrates the most craftiness and forcefulness of any French ruler we’ve seen thus far. He soon outgrows his need for Joan, and Henry V’s ghost looks on in rage while his generals take advantage of his gentle son to make themselves stronger in a weakening state.

It’s fair to say Tug of War: Foreign Fire is a monumental achievement. While productions of this length aren’t that unusual for a huge festival, to uncover this much new meaning in a text is precisely the kind of re-imagining Shakespeare needs to remain vibrant. Kudos to Gaines and company for going beyond the most well-worn portions of the folio, and seeing the potential in Shakespeare’s early writing. That said, it is a good thing the production has Henry V in the middle to anchor it, and it will be interesting to see what happens next fall, when Gaines has to use Richard III at the end of a marathon to supply its strongest text. But since most of the same actors will be returning, with a few locally famous additions, there is reason to stay excited. All of the actors in Foreign Fire who weren’t musicians played multiple large parts, and their ability to keep up such varied performances over such a long time is fantastic to witness. I’ve mentioned most of them so far, but Neil Friedman, Kevin Gudahl, Daniel Kyri, Barbara Robertson, and Alex Weisman also deserve citations for the staggering array of nobles and soldiers they portray. Yet despite its epic scale, Tug of War is rooted in individual actions and personalities. We see enough of the repercussions of war on normal people to understand what’s at stake, but we also see into the hearts of the leaders, which are truly driving events. Gaines writes in the program note that she was thinking of wars going back as far as Troy when she conceived this project. The balance this production achieves between heroes and the chorus is tragedy at its finest.

Highly Recommended

Jacob Davis

Reviewed May 22, 2016

For more information, see Tug of War: Foreign Fire’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing in the Courtyard Theater at Chicago Shakespeare Theater on Navy Pier, 800 E Grand Ave, Chicago. Tickets start at $85 when Foreign Fire and Civil Strife are booked together, or $100 for just one part. To order, call 312-595-5600 or visit chicagoshakes.com. Running time is six hour with four intermission. Playing through June 12.