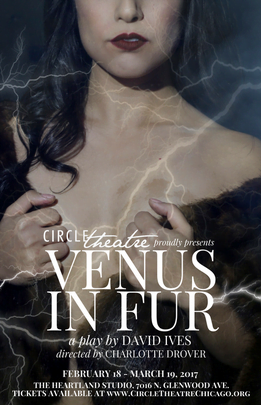

Venus in Fur

By David Ives.

Directed by Charlotte Drover.

Produced by Circle Theatre.

Playing at The Heartland Studio, Chicago.

The Dissembling Art and Power of Venus in Her Fur.

Late in the evening, a storm rumbles and flashes outside the window of a small office, continually threatening the power therein. Inside, after a long day of auditioning the deficient female talent that would be the lead to his adaptation of Sacher-Masoch’s 1870 novel Venus in Furs, writer-director Thomas Novachek (Zach Livingston) bemoans his dearth of suitable choices on the phone to his fiancée. Then, as if in ironical, divine retort to his frustration, in rushes Vanda Jordan (Arti Ishak), hours late for her audition, exuding a rudeness and a flighty shallowness of soul that makes Thomas roll his eyes as he attempts to expel this high-pitched dilettante from his office.

But Vanda will not leave. Her seemingly obtuse impudence is daring, and Thomas acquiesces to read with her for the part. But, ah!, the first line from her ash-painted lips finds a soulful register—as if issued from another’s breast entirely!—and Thomas, the auteur sophisticate, turns to her, struck dumb in astonishment, as if to behold for the first time his muse.

As they continue reading from his script, Thomas’ incredulity at Vanda’s transformative acting skills gradually transforms itself into admiration—then sensual possession. But as the two move back and forth between the script and the audition, the reality of their encounter blurs, until the seduction in the script bleeds into their exchanges, Vanda becomes Venus, and acting becomes true act—of dominance.

Circle Theatre’s production of David Ives’ Venus in Fur, directed by Charlotte Drover, is a two-fister of clever design and powerful ambiguity. Most of that, I think, lies in the actual script itself, but Drover’s direction and the stars’ performances accent this cleverness and ambiguity fairly well—perhaps even in unintended ways.

At least in the first three-quarters of the play, “intention” is as ambiguous a term as “power.” The play-within-a-play aspect of Ives’ script emphasizes this: the intentions and power-dynamic of the “audition” claim one interpretation; the “script” from which they read, another; and Vanda’s progressively bold actions, yet another, as she seems to wrest from Thomas the assumed powers of director, writer, and, finally—gender. It is a wonderfully crafted script, always shimmering illusively between ever-shifting lines of interpretation; always shifting elusively between shimmering perceptions of truth.

The staging of such a play must be no light task. The characters, particularly Vanda, are rendered layered and complex, if only by fact that they are called to continually transition between audition and script and maintain some kernel of honest, transcendent intention between them. The scrutiny of what is acting and what is acting-like-acting ought not bear considerable mention, but should pass simply into one’s reception of the performances under the principle of suspension of disbelief.

Yet I could not help sensing a faltering in the performances in the “audition.” Strangely—yet, again, perhaps intentionally—both Ishak and Livingston find depth and connection in the “script,” both having their best moments playing as Wanda and Severin, the lead characters. But Livingston as Thomas and Ishak as Vanda are bland and tiresome, oftentimes seeming rigidly rehearsed and shooting afar in their comedy to the big and the broad; Thomas has too little personality, Vanda too big, and the effect of the latter, being the more egregious to the given circumstances (i.e. coy-seeming manipulation), verges on the unbelievable. One wonders of the paltriness of the modern spirit and the richness it finds in narratives of the past.

Nevertheless, Ives’ script is layered and paced well enough that even the moments when the performances seem to stick out as performances, the circumstances shift with a new action and the script reclaims the apparent anomaly within the sway of its undulating momentum. If it’s not a sign of a slipped performance, it’s surely a sign of great writing.

Circle Theatre’s production of Venus in Fur is very entertaining, even if the comedy doesn’t always land or if you’re just not a person taken with comedy, even of the black variety. But what makes it more than mere entertainment are the various, timely issues it addresses—that Ives craftily intersperses in his script in such a way that everyone can feel their own, small vindication vicariously with their sympathetic character.

Obviously, there is the issue of gender and its narrative, social norms we’ve inherited culturally and integrated—consciously or unconsciously. In the play, Thomas has adapted his script from the 1870 novel: in other words, he has literally carried forward those supposed assumptions. Vanda finds this backwards, ignorant, and offensive; and it would appear that by her triumph over Thomas that, by the end, she has reset the power-dynamic in her favor. But how much she has undermined his 19th century views of women must be weighed against how much she plays into them to achieve her end. This is an apparent irony in the play, but one that begs deeper consideration for its reflective significance on her prevailing moral righteousness.

In regards to art itself, the play raises an even more essential issue of its medium: the ascendant interpretative paradigm (at least in the circles of the cultural literati) that all art be seen as a kind of Everyman/Everywoman/etc. pseudo-morality fable. At one point, Thomas challenges the notion that the individuals in his story stand for Man and Woman: why can’t they just be taken as particular individuals in a particular circumstance, he asks (in so many words)? This is a thorny issue, insidious in its counter-prejudicial prejudice; and while it is not dealt with at length in the play, the play cannot help but evoke it in its own gendered duality. Indeed, Director Drover ends the play with a strong impression of Vanda as a symbolic (or surreal?) epiphany of the goddess Aphrodite, thereby casting Vanda in a transcendent light. The audience member inclined to such post-show ruminations might well consider how this perspective on art delimits or expands our interpretation and appreciation of past art (e.g. Venus in Furs) and what effect it has on our approach to new works.

So much can be thought about and delighted in in David Ives’ Venus in Fur, its richness so playful and complex, that one would have to have no liking for drama, no capacity for humor, and no mind for consideration to not enjoy this production. Circle Theatre’s production has some stellar, some faltering moments, but overall it is a success worthy of attendance.

Recommended.

August Lysy.

Playing at The Heartland Studio, 7016 N Glenwood Ave., Chicago. Tickets are $28. Performances are Thursdays thru Saturdays at 8:00 p.m., and Sundays at 2:30 p.m. through March 19th. (Note: Industry Nights are at 8:00 p.m. on the following Mondays: February 27th, March 6th, and March 13th.) Running time is 90 minutes with no intermission.