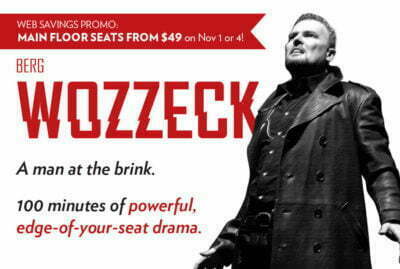

Wozzeck

Music and Libretto by Alban Berg

Based on the Play by Georg Büchner

Directed by Sir David McVicar

Conducted by Sir Andrew Davis

In a new production at the Lyric Opera of Chicago

Brass-Infused Madness

Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck is a fascinating object of study for students of drama. An early neurologist, communist, and political exile, Büchner was only twenty-three when he died in 1837, leaving his masterpiece unpublished and apparently unfinished. The culmination of his interest in the mind-brain dichotomy and social influences on behavior, Woyzeck was decades ahead of the development of naturalism, the style of scientifically-informed characterization advocated by the activist Émile Zola and utilized by Anton Chekhov, another doctor and dramatist. It was likewise decades ahead of expressionism, the attempt to represent an unstable mind from the inside, although perhaps in that regard, more firmly grounded in the romanticism Büchner was familiar with. But fortuitously, Büchner’s works survived to be discovered when the world was ready for them, and Woyzeck debuted in Vienna in 1914, in a world primed for it by Freud and Strindberg, and teetering on collapse. There, it was seen by the young composer Alban Berg, who was inspired to make it into an opera, but first had to complete his service in World War I.

I mention this because appreciating the idea of Wozzeck massively improves the experience of it. What Berg wrote is one of the first modern operas—his libretto is quite faithful to Büchner’s text, with the exception of the final scene, which has only a single line. There are no arias, and the music is heavy on brass instruments. The subject matter is also relentlessly brutal. The titular character, played by Tomasz Konieczny, was based on a severely mentally ill soldier who killed his common-law wife, and was of professional interest to Büchner. He is first seen acting as a valet to his captain (Gerhard Siegel), who condescendingly lectures him on his duty to raise his bastard son as a Christian, while Wozzeck sputters about his poverty. Wozzeck is much more verbal but no more coherent in the next scene, in which he earnestly describes to his friend, Andres (David Portillo) how freemasons congregate in a field to secretly murder good Germans. Wozzeck’s lover, Marie (Angela Denoke) is being pressured through a combination of bribes and physical force to have an affair with a drum major (Stefan Vinke). She is driven further from Wozzeck and disturbed by him when he enters seeking solace in Bible verses and claiming evil forces are chasing him. His paranoia worsens as his poverty forces him to allow the military to perform medical experiments on him in exchange for money, and eventually, when Marie actually cheats on him, the higher-ups know, and join in ridiculing Wozzeck.

The first voice we hear is that of Siegel’s tenor, which is bright and flexible, in disconcerting contrast to the darkness and heaviness all around. The captain calls himself melancholy, and he’s certainly ineffectual. Tomasz Konieczny is a powerful, sonorous bass-baritone, but Wozzeck is a role which requires him to make great use of his skill as an actor. An imposing hulk to begin with, this Wozzeck crumbles over the course of the show under the force of mad terror, which makes him terrifying in turn to all around him. What’s fascinating about Konieczny’s performance is how measured it is; Wozzeck is always human, deeply confused, and in great pain an embarrassment, which makes his decline all the worse. As his lover, Marie, soprano Angela Denoke is subjected to similar humiliations, but attempts to survive in more rational ways, which causes her to feel even more guilt and self-doubt. Director Sir David McVicar says that one of his goals with the antagonists was to make them less like caricatures and more like real people. So the captain, along with Sherratt’s doctor and Vinke’s drum major come across realistically as very, very bad people who are blinded by their self-importance and complacency to the tragedy unfolding in both massive and intimate ways all around them.

The characters who inhabit this world are casually violent, as well as anti-Semitic, and have just enough feelings to cause each other pain. Berg wrote his opera amid war and revolution, and in hindsight, it was a portent of where Germany was headed. McVicar’s original production, with a monochrome set design by Vicki Mortimer, foregrounds systematic violence with the tomb of an anonymous soldier looming over the stage, and medical equipment used during the quack doctor’s experiments being slowly lowered in and out. Scene changes are accomplished by actors whipping filthy white curtains across the stage as if it is an army field hospital, and designer Paule Constable (who also worked on War Horse) completes many disturbing stage pictures with stark, focused lighting from visible canisters. Berg retained the episodic structure of Büchner’s unfinished script, which included many songs of its own. Sir Andrew Davis’s magnificent accomplishment is that he, too, honors that episodic quality in each of the fifteen scenes, yet blends the brass-heavy atonal score with occasional melodic string interjections into a cohesive whole, which is reminiscent of the fluctuations of a heartbeat. At one hundred minutes long, the opera is just the right length; anymore and the music and design would overstay their welcome, but any less, and the atmosphere and story would not be done justice.

Highly Recommended

Jacob Davis

[email protected]

Reviewed November 1, 2015

For more information, see Wozzeck’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing in the Civic Opera House, 20 N Wacker Drive, Chicago. Tickets are $39-249; to order, call 312-827-5600 or visit lyricopera.org. Performances are November 4, 7, 12, 16, and 21 at 7:30 pm. Running time is one hundred minutes with no intermission.