Billy Elliot the Musical

Book and Lyrics by Lee Hall

Music by Elton John

Directed and Choreographed by Rachel Rockwell

Music Direction by Roberta Duchak

Produced by Drury Lane, Oakbrook

Billy Elliot Reinvented Better than Ever

Listen to my interview with Rachel Rockwell.

I developed a soft spot for Billy Elliot after seeing the Broadway production, and was impressed by director Stephen Daldry, but also annoyed by a few choices that I felt were holding the story back from its full potential. But director Rachel Rockwell’s new production at Drury Lane, the first Chicago regional production of this show, fixes all those problems and raises the musical to a true piece of art. This is the story of how a boy dancer from a doomed town had to fight a harrowing battle with himself, his family, and the culture where he lived so that he might just possibly have a chance at a future denied to everyone else he knew.

The story, originally a movie made in 2000, takes place in a northern England mining town at the beginning of the 1984 strike. Following years of economic underperformance, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher is determined to destroy the powerful miners’ union and reform Britain’s socialist economy. For people in Billy’s town, this means the loss of jobs they all depend on, and they are determined to resist through demonstrations and an open-ended strike, which will leave them dependent on support from sympathizers in other unions. They remain staunch socialists, but the show makes clear from the beginning that their cause is hopeless.

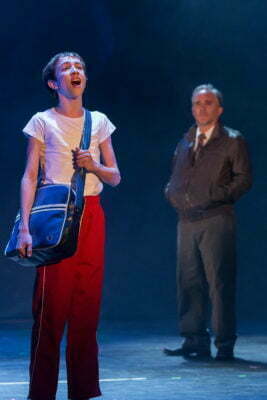

Eleven-year-old Billy (Nicolas Dantes on press night, alternating with Kyle Halford) is the son and younger brother of two of the miners. His mother’s dead, and they’re left caring for his half-senile grandmother (Maureen Gallagher). Billy’s father (Ron E. Rains) sends him to boxing classes, which Billy dislikes and is terrible at due to his reluctance to fight. But one day, he stays at the gym long enough to meet the ballet instructor, Mrs. Wilkinson (Susie McMonagle), who ropes him into joining the lessons. Billy has a natural aptitude for movement, but feels conflicted over an activity he considers gay. Billy’s cross-dressing friend Michael (Michael Harp) soothes his anxieties over that, a little, but there’s still the problem of what his family and the rest of town will think. And as clashes between the police and miners, especially Billy’s brother Tony (Liam Quealy) get worse, the men in Billy’s social circle are in no mood to tolerate an art form that not only betrays masculinity, but is also bourgeois, useless, and indicates a disturbing belief in individual talent, contrary to leftist solidarity built on workers’ interchangeability.

Rockwell’s directing eliminated the mugging for “aww” moments in the original, and instead allows the development of her protagonist to earn these moments legitimately. Dantes’s acting is amazing; his Billy is a complex character with little idea of how to navigate the world except by observing others’ unhappiness. Gallagher’s rough voice captures the regret and suppressed pain in the grandmother’s song “We’d Go Dancing,” in which she explains to Billy how social dances were the one relief in a long, unhappy marriage in which she and her husband could not communicate, due to the gender norms of the time and their despair at improving their economic condition. Following Mrs. Wilkinson’s song “Shine,” in which she exhorts her hilariously inept students to put on a façade of beauty to conceal their real condition, Rockwell puts Billy through an inventive moment of playing with his shadow. But not until the song “Expressing Yourself,” a joyous, albeit awkward, scene in which Michael invites him to put on a skirt, does Billy show any sign of happiness.

McMonagle’s Mrs. Wilkinson is a hard-as-nails teacher who seems mostly disillusioned with her job until she notices Billy and a chance to shake things up. She leads Billy on a journey of artistic development by contradicting or refining her original message in “Shine” with “Born to Boogie” after they begin private lessons. Rather than suppressing the ugliness in his life under a mask of style, this fast-paced song teaches him to use his emotions to create an audition piece for the Royal Ballet School. She’s excited by his progress, and sternly reprimands those who try dissuading him for their insecurity. But as forceful as she is, she has insecurities of her own. As Billy’s father, Rains gives a sympathetic performance who has a few humorous moments, but is far from a buffoon. His drunken ballad “Deep into the Ground” is a moment of discovery when he realizes how little he is passing onto his sons, and during his song “He Could Go and He Could Shine” with his older son Tony, he seems amazed himself at his change in attitude. Liam Quealy’s Tony, by the way, is a very sad character who is a “dinosaur” with no future before he is even past adolescence, and battles for a long time to avoid facing that. It’s great to see a show nuanced enough to make you feel for the supporting characters, while still being frank about their shortcomings.

The Drury Lane orchestra, conducted by Colin Welford, blares forth the power of the anthems “The Stars Look Down” and “Once We Were Kings” as well as the sweetness in Billy’s Swan Lake fantasy. Musical director Roberta Duchak also removed the annoying techno beat from “Electricity,” Billy’s audition piece, integrating it more with the rest of the show’s musical style. Kevin Depinet’s scenic design fleshes out Billy’s gritty, but cozy home as well as the dingy gym under a decaying industrial frame, and Maggie Hofmann’s realistic costumes convey the cold damp of the English winter. Christine Adair’s dialect coaching avoided the problem with the thick Geordie accents people complained about in other versions of this show, so that while the characters are clearly from the north, they are always understandable. Rachel Rockwell’s choreography cleverly mixed the confrontation between the police and strikers in “Solidarity” with the ballet lesson, emphasizing the ironic split in the working class, since both camps have daughters in Mrs. Wilkinson’s class. Billy’s dancing when he finally learns to express himself is partially martial—Mrs. Wilkinson had used boxing moves during their private lessons—and is authentic to his character. His flying scene is one of the biggest crowd-pleasers in a show full of them, and a welcome moment to recharge from the show’s generally high intensity.

The opening song in Act II, “Merry Christmas, Maggie Thatcher,” in which the cast wishes death on the Prime Minister, could, depending on your point of view, seem especially funny or cruel since Thatcher has died since the show was written. In his eulogy for her, British gay conservative pundit Andrew Sullivan said that while Thatcher was a homophobic oppressor, her message of achieving the full potential of one’s unique talents and being true to oneself regardless of the judgements of a conformist, parasitic, stagnant, socialist society inadvertently made Britain much more receptive to gay acceptance and weakened gender barriers. I don’t know how many British people would agree with that, but Billy Elliot the Musical suggests a change along those lines took place at this time for some reason. As much as Billy has to struggle with his and everyone else’s prejudices, he also contends with the guilt of potentially being the town’s only economic survivor, ballet now being a better career path than mining. I’ve heard some people in DuPage County might be scared off by the characters’ use of the words “feck” and “shite,” and I hope that’s not the case, because this production demonstrates Billy Elliot really is a moving, thoughtful piece of work. The characters’ contempt for middle-class notions of respectability is a major theme, as is the transformation of the chant “Solidarity forever! We’re proud to be working class” into “What we need is individuality.” Regardless of whether you are a person who sees much theatre, this show is an excellent choice, especially if you can share it with teens of your own.

Highly Recommended

Jacob Davis

This show has been Jeff recommended.

For more information, see Billy Elliot’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing at Drury Lane Theatre and Conference Center, 100 Drury Lane, Oakbrook Terrace. Tickets are $45-60 with discounts at matinees for seniors and students; to order, call 630-530-0111. Performances are Wednesdays at 1:30 pm, Thursdays at 1:30 pm and 8:00 pm, Friday at 8:00 pm, Saturdays at 5:00 pm and 8:30 pm, and Sundays at 2:00 pm and 6:00 pm through June 7. Running time is two hours and thirty-five minutes with one intermission. Billy Elliot is recommended for ages 13+. Please be advised that there is strong language, violence and some sensitive subject matter that is true to the story and plot. Parental guidance is suggested.