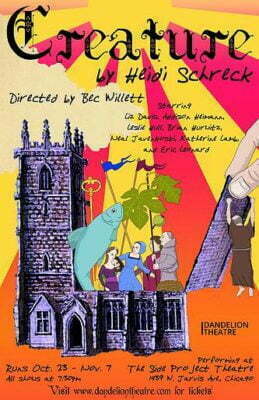

Creature

Directed by Bec Willett

Produced by Dandelion Theatre

Playing at The Side Project Theatre, Chicago

A Mystifying Vision, Sans the Revelation

Margery Kempe (1373 – c. 1438) was an English, orthodox Catholic laywoman who, after the birth of her first child, was tormented and tempted in her faith by visions of devils and demons until a vision of Christ led her to devote her life to becoming a saint. She is most well-known for her autobiographical book The Book of Margery Kempe, which describes, along with many of her other life experiences, her mystical visions; it is considered by some to be the first autobiographical text in the English language.1

It is on this historical figure that Heidi Schreck’s Creature is loosely based, “creature” being a reference to the term by which Margery refers to herself in her book. The title is also apt on account that Creature is so odd and ambiguous that it defies definition; it certainly defies intelligibility. Those expecting any of the usual theatrical fare, such as a compelling plot or sympathetic characters, will be disappointed by Dandelion Theatre’s production of Schreck’s off-beat comedy, as it offers up all the incoherence of a vision without any of the salvation of divine revelation.

In its most basic articulation, the story of Creature is the story of Margery Kempe’s (Katherine Lamb) quest for legitimacy as a mystic. The story begins shortly after the birth of her child, when she is met at her bed by a devil, Asmodeus (Brian Hurwitz), who teases her disguised as a priest. Margery’s Nurse (Liz Davis) brings news to her husband John Kempe (Addison Heimann) that Margery is claiming a devil is trying to eat her, and so a local friar, Father Thomas (Eric Leonard), is called in to hear her confession. Upon his arrival, Father Thomas finds Margery speaking nonsense and soon departs; whereupon Margery has her first mystical vision of Christ dressed in purple robes. It is from this moment onward that Margery decides to live her life as a saint.

The remaining 90 minutes of Creature show Margery apparently overcoming obstacles in her pursuit of sainthood. I write “apparently” because the forces that oppose her (ostensibly, her husband and her nurse) seem so ambivalent in their doubt that whatever obstacles they present to her legitimation as a mystic saint are resolved merely by the passage of time and not by any means on Margery’s part. In fact, the absence of any real conflict (aside from the hovering possibility toward the end that Margery may be burned as a heretic by non-present forces, i.e. the Church) leaves me confused as what this play is really about and why it was written at all. Moreover, my experience of Bec Willett’s production leads me to wonder whether anyone involved in this staging really knows, either.

For instance, in Willett’s production, Schreck’s supporting characters of Father Thomas, Juliana (Leslie Hull), and Jacob (Neal Javenkoski) seem superfluous. Father Thomas is certainly an ally and confidant to Margery, but how does he fit in with her goal of attaining legitimacy? He reads to her the visions from Juliana’s book, Revelations of Divine Love, and shows her an English translation of the Bible – but for what end? Margery eventually visits Juliana (i.e. Julian of Norwich, another medieval Christian mystic), but she seems crazy next to the reverent and composed Margery. What does such an outlandish portrayal of Juliana mean juxtaposed to the reserved Margery – that she is, by contrast, more sincerely devout? And what are we to make of Margery’s admirer, Jacob, when, after she kisses him he denounces her as a tempting manifestation of the devil? These are questions certainly in need of deep, dramaturgical meditation.

On the other hand, considering this play as plot-based may be incorrect, and the play may instead be more of a character study of Margery. Indeed, there are some intimations along this line that lead me to think her role as a woman is of primary importance for Schreck. But even this line of reasoning leaves me with little to understand the story by since the frequent remarks about Margery being a married woman or her husband calling her a “bitch” as he tries to force-feed her a cooked sirloin come across as occurrences of secondary importance in the story: Margery goes on doing exactly what she feels called to do, regardless, and these labels present no real conflict to her saintly lifestyle in the world of the play.

The nonsense of this story is rendered only more unintelligible by its presentation as a comedy taking place in the late-medieval era yet being acted in contemporary American dialect. At first I thought there was method to Schreck’s (as she calls it) “collision between the medieval and contemporary imaginations,” such as, perhaps, a commentary on contemporary skepticism to religious experience, or even the juxtaposition of medieval and contemporary views toward women. But if this is part of the story’s meaning it is poorly communicated, particularly since any contemporary parallels to the life of a medieval woman seem superficial and ironic.

Moreover, the play isn’t even funny. I’m thankful to Willett for underplaying the comedy of the play, but its unavoidable presence confuses our reception of Margery’s religious experience and casts a strange tone over the whole production. Is Margery to Creature what Isabella is to Measure for Measure, our shining light of authentic virtue? It seems not, as Margery’s visions are presented as slightly comical, as when one leaves her bloodied in a bandage after a cross falls on her head. How then are we to understand Margery? Where is the firm ground from which to interpret this ridiculous play?

If there is a coherent interpretation of Schreck’s Creature, Willett’s production does not bring it out. Instead, it bores one into a trance-like state of mystification, with scene after aimless scene without any discernible plot purpose or emotional engagement – just dead wood, like the minimalist set design. I’m sorry to say that neither the subdued beauty of Lamb’s performance nor the much-appreciated, vivacious energy of Hull’s offers enough redemptive value here to save one from the purgatorial slumber of this production. Miserere mei, indeed.

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margery_Kempe (viewed 10/30/2015)

Not Recommended

August Lysy

Reviewed October 31st, 2015

Playing at The Side Project Theatre, 1439 W Jarvis Ave, Chicago.