Design for Living

By Noël Coward

Directed by Derek Bertelsen

Produced by Pride Films and Plays

At Rivendell Theater, Chicago

Wit is Ornamental in this Old-Fashioned Comedy

Pride Films and Plays artistic director David Zak has expressed an interest in showcasing the many eras of LGBT-related art. The company’s last show, The Boy from Oz, was a revue themed around of the life of 70s disco songwriter Peter Allen, and their next show, Ten Dollar House, is a work of historical fiction which debuted earlier this year. But their current production, Design for Living, is a throwback from 1932. This comedy by Noël Coward was controversial for implying its main characters are in a bisexual love triangle, and debuted on Broadway because censors in refused to allow it to run in Coward’s native England. Today, director Derek Bertelsen treats it as an exercise in art deco visuals, allowing scenic designer G. Maxin IV, costume designer John Nasca, and hair/make-up designer Brian Estep to fill Rivendell’s storefront with metallic geometric patterns and swirls to match Coward’s rhetorical intricacies. The story itself is amusing, and should please Coward fans as well as people curious about comedies from the inter-war period.

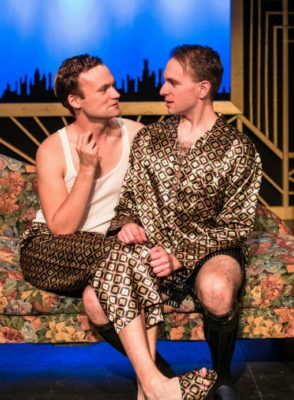

Interior decorator Gilda (Carmen Molina) lives in a Paris flat with her painter boyfriend, Otto (Matthew Gall). At rise, he’s away on business, and Gilda is entertaining her friend, the fussy gay art dealer Ernest (Edward Fraim). He is frustrated that she refuses to marry Otto; her claim to love him too much for anything as mundane as that seems like a nonsensical evasion of adult responsibilities. When Otto arrives home, Gilda informs him that their old friend Leo (Kevin Webb) has just arrived in town. Once Otto and Ernest are off to meet him, Leo reveals himself, having been hiding in Gilda’s bedroom the whole time. The two are very sad to have hurt Otto in by having an affair, but hope they can all go on being friends. But Otto feels betrayed by them both, and storms out. Time goes by; Gilda and Leo settle in together, this time in London, and Gilda begins resenting Leo’s success as a playwright. Fed up with high society parasites, she agrees to an affair with Otto, turning the tables on Leo. Shortly after, Gilda abandons both of them, and Leo and Otto realize their romantic feelings for each other. But years later, they still want to confront Gilda, and pursue her to New York, where she and Ernest have formed another relationship of convenience.

This play is long enough that these dramatic complications are easy to follow, as far as plot goes. The characters make many statements about their motivations. Gilda is initially uncomfortable with her femininity, but as the years go by, she gets over it. Otto says she also has a tendency to look for the bad in everything, and that never changes. Molina’s Gilda is poised, but clearly impatient, stifled, and confused. Webb’s Leo is a little crankier and more assertive than Gall’s Otto, who needs to be dumped by Gilda twice before he develops a sense of guile. But overall, this is a light comedy, with characters slightly on the cartoonish side. Coward foresaw the need to bring in more people for the final scene to raise the stakes and create a more awkward situation, until then, the humor mostly derives from wit appropriate for drawing rooms. Several situations and lines are quite clever satire, such as Leo’s frustration with vague theatre critics, and the prevailing tone is one of bemusement.

Bertelsen has dispensed with any ambiguity surrounding Otto and Leo’s attraction to each other. It makes sense to not be bound by the restrictions of eighty years ago, but it’s a little odd that Otto and Leo would then make such trouble for Gilda, since it seems they already found happiness without her. However, their return sets up the play’s hilarious climax, by allowing everyone to finally employ their most scathing verbosity. Also updated is Kallie Noelle Rolison’s sound design, which includes swing versions of contemporary pop songs. Playing with music in this way makes mounting a comedy of manners in the twenty-first century even more a celebration of a style. For older audience members, Pride Films and Plays’ Design for Living is a visually engrossing chance to enjoy Noël Coward’s writing; for younger ones, it’s an interesting view into a world normally seen only in black and white movies.

Recommended

Jacob Davis

[email protected]

Reviewed October 25, 2015

This show has been Jeff recommended.

For more information, see Design for Living’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing at Rivendell Theater, 5779 N Ridge Ave, Chicago. Tickets are $22-27; with discounts for students and seniors; to order, call 1-800-737-0984 or visit pridefilmsandplays.com. Performances are Thursdays-Saturdays at 7:30 pm and Sundays at 3:30 pm through November 22. Running time is two hours and thirty minutes, with one intermission.