Die Meistersinger Von Nurnberg

Music & Libretto by Richard Wagner

Conductor Sir Andrew Davis

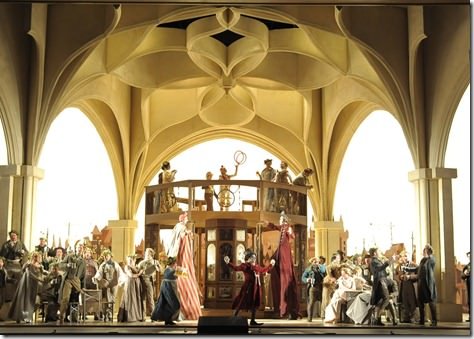

Stage Direction by Marie Lambert

At the Lyric Opera of Chicago

Wonderful musical variety demonstrates Wagner’s genius

Perhaps what is most appealing about Wagner’s 1868 opera Die Mestersinger, despite the near 4 hour and 45 minute running time, excluding intermission, is the sheer accessibility of the subject matter. Rather than taking old folk tales and German mythological heroes for its theme, the opera tells an all too strikingly relevant story of a Guild of Master-singers—a sort of modern German adaptation of Grecian bards, with music added—and the struggle of an outsider and up-start, in this case the noble Walther von Stolzing, against the insensible artistic establishment.

There is a love story too, of course; Walhter (Johan Botha) has fallen for Eva (Amanda Majeski), the only daughter of the town’s wealthy goldsmith (Veit Pogner). But Pogner has already promised his daughter to whoever should emerge victorious in the music/poetry competition scheduled for the feast day of St. John the Baptist. To compete, one must be a member of Nuremberg’s illustrious artistic guild of “Master-signers”; and to become a master-singer it is necessary to perform for the committee an original song, set to ones own verse, that adheres to the carefully set down rules of the Guild as set down in its “Tabulatur”. Obviously, the Knight von Stolzing has a rival, the priggish town clerk and “marker” of the guild, Sixtus Beckmesser; but he finds support in the sage veteran Master-singer, local cobbler Hans Sachs (James Morris). Act III is certainly longer than it has to be, but one never feels one is wasting one’s time devouring these nearly 5 hours of what is surely one of the greatest stage representations ever produced of the outlook and sentiments of European Romanticism.

In the art of 19th century High Romantic orchestration, making use of a much larger cohort of forces than, for instance, Beethoven ever had, Wagner is without peer. Like contemporaries such as Tchaikovsky, and to a certain extent the Strausses, Wagner usually orchestrates in blocks of instrument-types; that is to say, where the strings are covering one line, the winds are hardly ever occupied with the same line, but rather occupied with contrasting, accompanying material, and vice versa. The music is, by terns, rich and murky; contrapuntal and sublime, joyous, and jolly, and even disarmingly simple and straightforward. In this it has all the stylistic variety of the celebrated late String Quartets of Beethoven, and at least some of their sublimity.

Although Wagner never wrote anything as simply perfect as, for instance, the andante theme in Beethoven’s opus 131 quartet, he triumphs, in his way, in the often revived “Prize Song” which Walther sings after he has, with the help of Sachs, learned to harness his natural musical inspiration into something fully mature and well formed. It is also worth noting that Wagner’s art, in writing music dramas, was fundamentally different from Beethoven’s in many ways. Whereas Beethoven was attempting to speak directly “to god” as he was once quoted as saying, within the confines of pure instrumental music, Wagner dramatizes the often tragic attempt of human beings to seek the divine, the good, and the beautiful in a sordid world. Wagner might very well have agreed with Mahler, when the latter wrote, in his case referring to the symphony, that it should be, “like the world” and “contain everything”. The difference is that Wagner’s taste is second to none. The music of Mahler, on the other hand, whose taste was comparatively deficient, is too often mawkish and sickening.

It is a testament to the greatness of James Morris (Sachs) that he was far and away the star of the show in the first two acts, before Lyric General Director Anthony Freud came out after second intermission to say that Mr. Morris asked for the audiences understanding, in that he had been suffering for a cold for 2 weeks. Despite this, Morris sang better than I have ever heard him sing in Acts I, and II. Johan Botha’s (Walther) is largely un-remarkable, though you can hardly blame him for trying to pace himself through this mammoth opera. But Botha does retain a certain sweetness, though not as much power as one would like. His “Prize Song” is quite affecting, but it probably should soar a bit more than it does. Perhaps more impressive is Bo Skovhus as the villain Beckmesser, who is arresting throughout. The Lyric Opera Orchestra, led by Music Director Sir Andrew Davis, is to be congratulated for the prodigious technical feat of an executing such a titanic, and technically demanding opera. If anything, the strings got stronger as the night went along, and I have rarely been so satisfied with Lyric wind section, as I was yesterday evening.

In seeing Die Mestersinger one especially feels the injustice of blaming Wagner for laying the seed for how recondite, un-popular, and out of touch much classical music often became under the guise of modernism. To say this music is gorgeous but without direction is willful ignorance; and against the beauty of Wagner the experimentalists will always seem a gross perversion; his high-romantic successors, somewhat of a farce.

Highly Recommended.

Gabriel Kalcheim

Date Reviewed: February 12, 2012

At the Lyric Opera of Chicago thru March 3, 2012