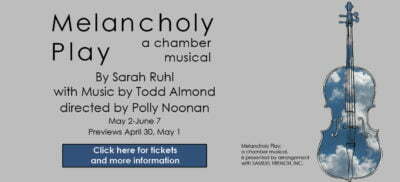

Melancholy Play: a chamber musical

By Sarah Ruhl

Music by Todd Almond

Directed by Polly Noonan

Produced by Piven Theatre Workshop, Evanston

Chamber Music Was Just What Sarah Ruhl Needed

Chicago playwright Sarah Ruhl has worked with Piven Theatre Workshop ever since she was a child. The Evanston-based training center produced many of Ruhl’s early plays before she became a nationally-acclaimed writer, including the first performance of Melancholy Play in 2002. Ten years later, Ruhl revisited her early work with composer Todd Almond, and added a string quartet and piano accompaniment. The new musical version of Melancholy Play is now being produced for the first time in the Midwest at Piven, and provides Ruhl’s poetic writing with the perfect means for delivering the sensual, emotional impact she desired.

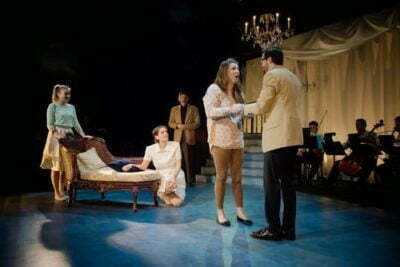

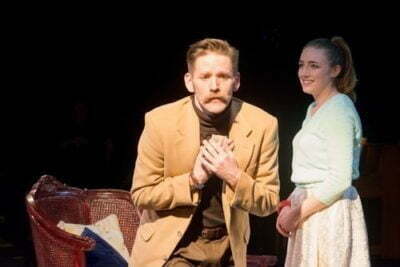

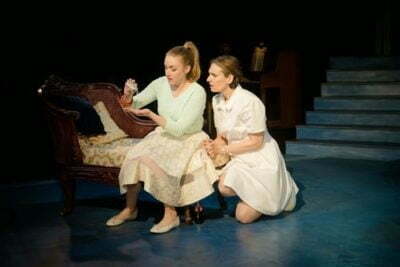

The story concerns Tilly (Stephanie Stockstill), a young woman suffering from what Ruhl, in a deliberately Jacobean turn of phrase, calls “melancholy,” persistent sadness with no external cause. It is not quite the same thing as severe depression, since Tilly still attends to her duties as a bank teller and maintains a social life, but her sadness is apparent in everything she does. This makes her irresistibly attractive to her tailor, Frank (Chris Ballou), her therapist, Lorenzo (Ryan Lanning), and her hairdresser, Frances (Lauren Paris). They each see something beautiful in her pain, as if it is a sign of purity from temptations, or perhaps lovesickness, and after she begins dating Frank, he collects a vial of her tears. This does not deter Lorenzo and Frances from making their own moves to seduce Tilly, and even Frances’s girlfriend, the English nurse Joan (Emily Grayson), becomes infatuated after their first meeting, when Tilly praises Joan’s orange-rimmed irises and teeth that will look appropriate in old age.

However, at Tilly’s birthday party, when Lorenzo, Frances, and Joan display their affection, Tilly suddenly becomes happy, and only gets more and more blissful. This is very surprising and upsetting to everyone else, for though Tilly remains as poetic and appreciative of everything as she was before, she’s no longer as needy or vulnerable, and therefore, less attractive. Tilly once compared sad people to almonds: while tasty, they dry you out and don’t alleviate hunger. When Frances gets hold of the vial of Tilly’s tears, she drinks them, and transforms into an almond. This state is more analogous to real-life depression, and Tilly is left to unite her admirers in a rescue operation.

Polly Noonan directs this play with an appropriate balance of Ruhl’s trademark whimsy and the seriousness alluded to by the subject matter. Each of the actors sings their big song with pathos and the appropriate volume for the intimate Noyes theatre. I especially enjoyed Stephanie Stockstill, who, as Tilly, adds some sense to the character’s earnestness and emotional swings. Tilly points out that in real life, sad people don’t dress as prettily as she does (costume designer Stephanie Cluggish provides her with a flower-patterned dress), but instead wear sweatpants and don’t take care of themselves. Ryan Lanning gets the most over-the-top comedic scenes as Lorenzo, who is from an unspecified European country and has no professional boundaries.

The singers often form quartets to match the two violins, viola, and cello. The original production seems to have used only a cello, and the addition of the piano and other string instruments makes a huge improvement in the show’s mood, which is not clearly subdued and semi-satirical. Aaron Benham’s musical direction is not intrusive; the sound blends with the actors during spoken lines, and supports them during their many songs. Almond’s music (and his name is something Ruhl could have come up with) is usually soothing, although there are a few dramatic moments, like “O for the Melancholy Tilly.” Jacob Watson’s scenic design emphasizes otherworldly beauty: the portal behind the onstage musicians is covered in white curtains, and dim chandeliers dangle over the actors. This is consistent with Ruhl’s original stage directions, which avoid realism, making the space the interior of someone’s mind and a manifestation of Tilly’s liking for simplicity.

As absurd as this play is, it is not a high-energy farce, and I do not know why it was advertised as such. Ruhl’s style is to regularly make references to images and ideas from classical films and novels that conjure certain emotional responses, such as when Tilly describes somebody as beautiful, “like Europe before the war,” or declares in her blissful state that she feels like she could go on a sailing ship for three years, disguised as a boy. It’s the sort of symbolism that’s hard to connect to anything in particular, but you get what she means. The orchestra helps to avoid turning these amusing moments into laugh-lines, which they aren’t, and I wonder if Ruhl’s work generally would benefit from more heavy use of music. In the same way that Ruhl fuels her writing with references that float around amorphously in the cultural atmosphere, this musical is not about real bi-polar disorder, but rather, the perception of it. In that way, Melancholy Play is not nearly as dark as it could be and I found the ending unsatisfactory, but it is a serious, thoughtful, and, well, melancholy, work of art.

Recommended

Jacob Davis

[email protected]

Reviewed May 2, 2015

For more information, see Melancholy Play’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing at Piven Theatre Workshop, 927 Noyes Street, Evanston. Tickets are $20-35; to order call 847-866-8049 or visit www.piventheatre.org. Plays Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays at 7:30 and Sundays at 2:30 through June 7. Running time is 95 minutes with one intermission.