2666

Based on the Book by Roberto Bolaño

Directed and Adapted by Robert Falls and Seth Bockley

Produced by Goodman Theatre, Chicago

Goodman Theatre Pushes Itself Farther Than Ever and Triumphs

One of the most anticipated, bizarre, and audacious works in the American theatrical landscape finally makes its debut at the Goodman after years of development. 2666, adapted from the posthumously published novel by Roberto Bolaño, is a five-and-a-half-hour long epic narrative which, like the Chilean author’s novel, radically changes styles with each act. Goodman artistic director Bob Falls took on this project with the sort of expansive vision which can only be driven by limitless ambition and admiration for his source, and yet, even he brought in a co-writer and director, the first time working at the Goodman that Falls had done so. Even with the administration’s support, 2666 required a million-dollar grant from an actor-turned-monk-turned-Powerball winner to finally be produced. The result is a work of such complexity and scope that it is daunting to even describe. But it is one the theatre scene is ready for. Tickets are already hard to come by, and those who attend this masterpiece are assured an unforgettable performance which seems to encompass the entirety of human experience.

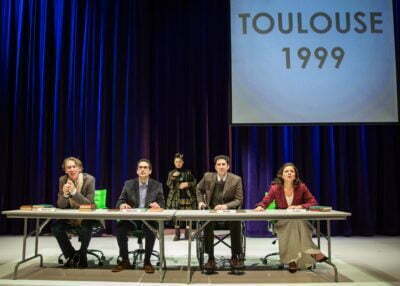

2666 adds in fantastic elements slowly over the course of its five acts. The first, The Part About the Academics, places us in the most mundane realm of all, in which, as Wallace Stanley Sayre said, the politics are so vicious because so little is at stake. Sean Fortunato, Lawrence Grimm, Demetrios Troy, and Nicole Wiesner play four European scholars obsessed with the enigmatic German novelist Benno von Archimboldi. The man has produced a vast number of novels, all baffling in distinct ways, yet despite being short-listed for a Nobel Prize each year, very little is known of him. His followers only know that he was born in Prussia in 1920. The academics form a love quadrangle, they debate Germans at 1990s conferences with titles like “Eroticism and Guilt in Post-War European Literature,” and they meet a painter who cut off his own hand, but Archimboldi remains elusive. Their story is told mostly through direct address, which makes it feel like an audiobook with occasional visual aids. But then, the faintest of clues emerges. Archimboldi has been sighted in Santa Teresa, Sonora, Mexico, and the academics abandon everything in hot pursuit. What they find is horror that shatters their removed, literary world.

In Part II: The Part About Amalfitano, we see the story of Santa Teresa’s local Archiboldian professor, Oscar Amalfitano (Henry Godinez), and his daughter, Rosa (Alejandra Escalante). Here the style of the play shifts, as heightened humor balances out encroaching madness and violence. Santa Teresa is based on Juarez City, Chihuahua, a border city famous for its massive post-NAFTA industrial parks and hundreds of inexplicably dismembered women. Amalfitano hears voices and remembers through flash-backs how his wife lost her mind when she became obsessed with a poet. He worries his daughter could be slain if they do not leave. In The Part About Fate, African-American journalist Oscar Fate (Eric Lynch) is dispatched to cover a boxing match in Santa Teresa, much to his displeasure. There, he encounters Rosa, rebelling against her father by hanging out with dangerous scum, and journalist Guadalupe Roncal (Sandra Delgado), who is investigating the murders. Much of this section is told through film, as the surrealism and psychological horror of Santa Teresa mounts during Faith’s sojourn into the nightlife that continuously devours its inhabitants.

Up until this point, audience members may be tolerant, but somewhat grudging, of the story’s shifts in focus and expository delivery. Part IV, The Part About the Crimes, is where 2666 really picks up. While an incompetent, compromised, and indifferent police force fails to solve the murders, the audience receives a steady stream of clinical descriptions of dead women. Most of the police are openly misogynistic, but two honest ones struggle against the system. Juan de Dios Martinez (Juan Francisco Villa) investigates Klaus Haas (Mark Montgomery), the menacing, unbalanced German man the police pin the murders on, even though they continue after Haas is incarcerated. He also doggedly pursues a relationship with the much older asylum director, Elvira Campos (Janet Ulrich Brooks). Their story is a rare bit of tenderness and love in Santa Teresa, but Elvira warns him that gynophobia is Mexico’s national psychosis. The other good cop, Lalo Cura (Adam Poss), whose name means “madness,” insists on pursuing leads on the dead women, even when they point toward wrongdoing by the powerful and ruthless. The recitation of murders in this section, which has the most action performed in the present-tense of any act so far, ramps up the tension as the characters hurdle toward disaster.

The final part, The Part About Archimboldi, is a fairy-tale theatre-goers should discover for themselves. It doesn’t exactly explain everything, but thematically, it ties the show together, and provides yet more strong performances and breath-taking design. The complete show is far more than the sum of its parts; each act could be a play in itself (not necessarily a good one), but together, they create an entire world we see refracted and contoured in endless variations. We can guess that the final part will be in the style of magical realism, but the direction and writing build to it, while exploring as varied a realm of themes and feelings as the Archimboldi books under discussion in Act I. Although the Owen’s stage space is limited and there are many shifts in location, the Goodman’s design team is at the top of their game. Walt Spangler’s simple set designs suggest the Sonoran desert and a Crimean forest with just a few props, and lighting by Aaron Spivey. Ana Kuzmanic’s costume designs fit a huge range of characters from an eighty-year period, making each distinctive, and Richard Woodbury and Mikhail Fiksel’s sound design establishes each of the five angles we see 2666 from. But most prominent are Shawn Sagady’s projections, which contribute most of the show’s magic and toy with the processes of the mind.

Of course, this show’s success depend just as much on its fifteen actors, who each turn in marathon performances in multiple roles. Besides the twelve already mentioned above, Charin Alvarez is captivatingly tragic as Amalfitano’s wife, for whom madness was contagious. Yadira Correa has several comic roles, but also plays the vivacious and ignorantly carefree Rosita, who is a contrast with Escalante’s fatalistic, self-aware Rose. Jonathan Weir appears in several supporting roles which range from the kindly, but ineffectual and frustrated Dean Guerra to the cartoonish, deranged Romanian fascist General Entrescu. The other actors are all stunning as well, not only for their stamina and their commitment to character, but because they are able to navigate 2666’s many changes in style. Many times they are hardly recognizable from all of the transformations they go through, so convincing is the illusion they create.

In a time when most new plays are ninety-minute naturalistic one acts, 2666 is something very different and daring. However, there are plenty of antecedents for it. Falls himself cites Nicholas Wright’s adaptation of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, but closer to home we’ve had The Hypocrites’ All Our Tragic and The House Theatre of Chicago’s Hammer Trinity, both of which dwarfed even 2666 in length and complexity of plot and staging. But those were performed in Wicker Park’s Den and Chopin theatres. Offering an unknown quantity like 2666 in the Goodman is a bold experiment, even though it was one which had evidence to support its validity. Watching the videos in Part III, it is hard to avoid thinking that were Falls not already the artistic director of a theatre, he would never have chosen the stage as his medium for this story. And yet, the stage’s transient, non-literal quality winds up serving 2666 very well. The actors’ transformations and the audience’s obligation to fill in gaps in the scenery with their own imaginations draw them into the surreal universe. This project is a magnificent feat of storytelling. Obviously it’s not something one goes to casually just because the evening was open, but for those looking for a great theatrical experience, this is it.

Highly Recommended

Jacob Davis

[email protected]

Reviewed February 16, 2016

This show has been Jeff recommended.

For more information, see 2666’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing in the Owen at the Goodman Theatre, 170 N Dearborn Ave, Chicago. Tickets are $20-45 with discounts for students with valid ID, to order, call 312-443-3800 or visit GoodmanTheatre.org. Performances are Tuesdays-Saturdays at 6:30 pm and 1:00 pm on Sundays through March 20. Running time is five and a half hours with three intermissions. Show contains adult language and descriptions of extreme sexual violence.