Sancho: An Act of Remembrance (Shakespeare 400 Chicago)

Written and Directed Paterson Joseph

Co-Directed by Simon Godwin

Produced by Oxford Playhouse and Chicago Shakespeare Theater

How to Become a Hero with Style

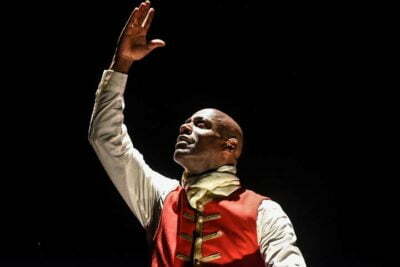

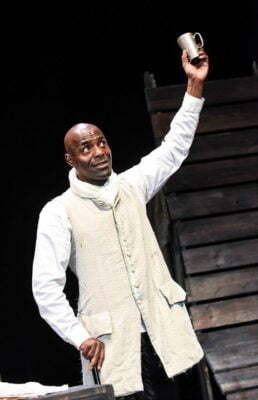

So far this year, Chicago Shakespeare’s World Stages program has hosted two high-quality, yet very different, Shakespeare productions from Eastern Europe. In a change of pace, their latest offering, Sancho: An Act of Remembrance, focuses on a historical figure for whom Shakespeare was an important, but not the sole source of inspiration in his own life. Charles Ignatius Sancho became the first Black Briton to vote in 1774. A writer, actor, shopkeeper, and musician, he is the latest black historical figure to be the subject of a one-man show in Chicago. The man who plays him, Paterson Joseph, is as charming as his subject, and is also the author of this nuanced portrait of a black man who rose from slavery in the heart of London.

Joseph enters the theatre as himself, and his warmth and cleverness immediately win the audience over. He first became aware of Charles Ignatius Sancho by finding Thomas Gainsborough’s portrait of him in a history book about Black Britons, and was fascinated by the man’s expression as much as his existence. But he did not write this play for any political reason, he reassures us. He wrote it because he was jealous of his white friends who can get roles in British costume dramas, and wanted to give himself the opportunity to appear in eighteenth century gentlemen’s garb (Sancho’s costumes are by Linda Haysman). And then, he just as gallantly quotes from several British historical documents demonstrating monstrous cruelty against African people, and with a sardonic smile, transforms into our prissy, lisping, unlikely, and if anything, even more engrossing hero.

We meet Charles Ignatius as he is posing for Gainsborough. His first words to us are naughty speculation on what King George III wears to bed, since it obviously isn’t the gold finery in his portrait by Allan Ramsay. A valet to a duke has no business being modest, he declares, particularly not when he has a story to tell. Charles Ignatius was born on a slave ship. His mother died birthing him he supposes, and his father killed himself when he saw he was to be a slave. And at this point the narrator is no longer so jocular, for despite his friendship with abolitionist priests, it is a cruel theology that damns a man for such an act. But the boy was picked up by a nobleman, and sent to England as a literal pet for three spinster sisters. The weird sisters, as he calls them, punished him for touching books, but they thought it amusing to dress him up and have him perform in plays. Thus he appeared as Sancho Panza in a Don Quixote adaptation. His moving performance, for as a child, he did not realize that his scene partner was not really dead, and cried real tears, won him the affection of a duke. Thereafter, his new patron’s family protected him and surreptitiously taught him to read Cervantes, Shakespeare, and all the other masters. The fabulous Charles Ignatius Sancho was born.

We meet Charles Ignatius as he is posing for Gainsborough. His first words to us are naughty speculation on what King George III wears to bed, since it obviously isn’t the gold finery in his portrait by Allan Ramsay. A valet to a duke has no business being modest, he declares, particularly not when he has a story to tell. Charles Ignatius was born on a slave ship. His mother died birthing him he supposes, and his father killed himself when he saw he was to be a slave. And at this point the narrator is no longer so jocular, for despite his friendship with abolitionist priests, it is a cruel theology that damns a man for such an act. But the boy was picked up by a nobleman, and sent to England as a literal pet for three spinster sisters. The weird sisters, as he calls them, punished him for touching books, but they thought it amusing to dress him up and have him perform in plays. Thus he appeared as Sancho Panza in a Don Quixote adaptation. His moving performance, for as a child, he did not realize that his scene partner was not really dead, and cried real tears, won him the affection of a duke. Thereafter, his new patron’s family protected him and surreptitiously taught him to read Cervantes, Shakespeare, and all the other masters. The fabulous Charles Ignatius Sancho was born.

But life turns out less than fabulous for a freedman in eighteenth century London. In the latter part of the play, Joseph introduces us to Sancho twelve years later, after having been freed/fired for developing a limp, and with a rather unexpected wife and seven children. The economy is hard on a gentleman-grocer, and he no longer finds fops as amusing as when he was one. He still peppers his speech with Shakespearean allusions, but his verve has faded. And either he is getting less resilient, or racism is getting worse, because hearing people viciously argue against abolitionists is deeply disheartening to him. But this is what Sancho’s life has truly been leading up to; there is no secret ballot at this time, and voting is done by mob action. To cast his vote will require extraordinary courage and conviction. But underneath his campiness, there’s a man who knows the horror of slavery, and has always insisted on being recognized as what he’s worth.

But life turns out less than fabulous for a freedman in eighteenth century London. In the latter part of the play, Joseph introduces us to Sancho twelve years later, after having been freed/fired for developing a limp, and with a rather unexpected wife and seven children. The economy is hard on a gentleman-grocer, and he no longer finds fops as amusing as when he was one. He still peppers his speech with Shakespearean allusions, but his verve has faded. And either he is getting less resilient, or racism is getting worse, because hearing people viciously argue against abolitionists is deeply disheartening to him. But this is what Sancho’s life has truly been leading up to; there is no secret ballot at this time, and voting is done by mob action. To cast his vote will require extraordinary courage and conviction. But underneath his campiness, there’s a man who knows the horror of slavery, and has always insisted on being recognized as what he’s worth.

It’s remarkable how Joseph nearly plays two characters: the younger, brasher, and older, wiser Sancho, and how he is equally convincing and magnetic as each. The real Charles Ignatius Sancho was hobbled in his acting career by a speech impediment which Joseph chose to interpret as a lisp; but in Joseph’s mouth, it’s an extraordinary tool for conveying subtlety as well as emphasis, wit as well as poignancy. In a time when Europe is agonizing over multiculturalism, Joseph wrote this play in part to demonstrate that London has already been a multicultural society for hundreds of years. For Americans, the story is a reminder of the importance of the right to vote, and the dignity intrinsic in exercising it. In case it’s not obvious already, Paterson Joseph is wonderful company, and some lucky audience members may even get an opportunity to dance with him. It’s a pity he’s here for so short a time; there are only six performances of Sancho: An Act of Remembrance in total. Hurry before he’s gone.

It’s remarkable how Joseph nearly plays two characters: the younger, brasher, and older, wiser Sancho, and how he is equally convincing and magnetic as each. The real Charles Ignatius Sancho was hobbled in his acting career by a speech impediment which Joseph chose to interpret as a lisp; but in Joseph’s mouth, it’s an extraordinary tool for conveying subtlety as well as emphasis, wit as well as poignancy. In a time when Europe is agonizing over multiculturalism, Joseph wrote this play in part to demonstrate that London has already been a multicultural society for hundreds of years. For Americans, the story is a reminder of the importance of the right to vote, and the dignity intrinsic in exercising it. In case it’s not obvious already, Paterson Joseph is wonderful company, and some lucky audience members may even get an opportunity to dance with him. It’s a pity he’s here for so short a time; there are only six performances of Sancho: An Act of Remembrance in total. Hurry before he’s gone.

Highly Recommended

Jacob Davis

[email protected]

Reviewed February 17, 2016

For more information, see Sancho: An Act of Remembrance’s page on Theatre in Chicago.

Playing in the Upstairs Studio at Chicago Shakespeare Theater, 800 E Grand Ave, Navy Pier, Chicago. Tickets are $38-48; to order, call 312-595-5600 or visit chicagoshakes.com. Performances are through February 21. Running time is eighty minutes.